From the Introduction

Despite its lip service to secular ideals, Indian cinema in general has contributed significantly to the celebratory construction of Hindu nationalist discourse. It has done so by reviving precisely those tenets of social organization and gender politics which have been invoked by the nationalist discourse and which are derived from Hindu mythology. It is notable, however, that a specific genre within Indian cinema—the Muslim film—reverses the binarism of Hindu and Muslim identities. This genre represents the Muslim not as masculine, fundamentalist, and separatist, but rather as feminine, exotic, and seductive. This apparent anomaly has been explained by Faisal Devji in his recent essay, “Hindu/Muslim/Indian.” Devji argues that the latter “benign” construction of the Muslim in popular texts fulfills a dual function for Hindus. First, it counters the putative threat of the Muslim, who is commonly viewed as the “enemy within.” Second, the representation of the Muslim woman as a figure of romance in literature and film “elicit[s].. pleasure in the shape of a rape fantasy.” Devji reads this fantasy as a mock punishment meted out to the Muslim whose presence not only reactivates the painful memory of the partition, but who is also believed capable of re-enacting that violent history….

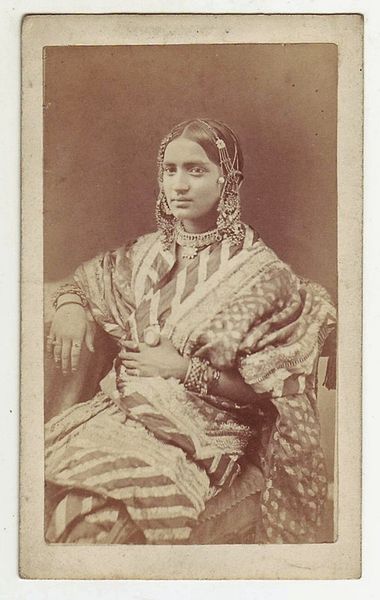

I shall extend Devji’s argument by illustrating that, in a specific subgenre of the Muslim film—the tawaif or courtesan film—not only does the representation of the Muslim woman as a tawaif seduce her Hindu audiences (by, in effect, “asking for” her rape), but the focal point at which this occurs is during certain key scenes in which the tawaif unveils herself to the pro-filmic and, by extension, to the film audience. What Devji’s argument does not address is the popularity of the tawaif film with its equally devoted Muslim audience. Nor can the argument that the film extracts a public confession from the Muslim imaginary for the internalized “guilt” of being different within an aggressive homogenizing national culture, explain that appeal.

I will argue via Pakeezah and Umrao Jaan that the tawaif film interpellates “Hindus” and “Muslims” into different subject positions by employing different textual strategies.