This book is available to read for free online at the University of California Press E-Books Collection.

“These South Indian devotional poems show the dramatic use of erotic language to express a religious vision. Written by men during the fifteenth to eighteenth century, the poems adopt a female voice, the voice of a courtesan addressing her customer. That customer, it turns out, is the deity, whom the courtesan teases for his infidelities and cajoles into paying her more money. Brazen, autonomous, fully at home in her body, she merges her worldly knowledge with the deity’s transcendent power in the act of making love.

This volume is the first substantial collection in English of these Telugu writings, which are still part of the standard repertoire of songs used by classical South Indian dancers. A foreword provides context for the poems, investigating their religious, cultural, and historical significance. Explored, too, are the attempts to contain their explicit eroticism by various apologetic and rationalizing devices.”

Poets and Padams

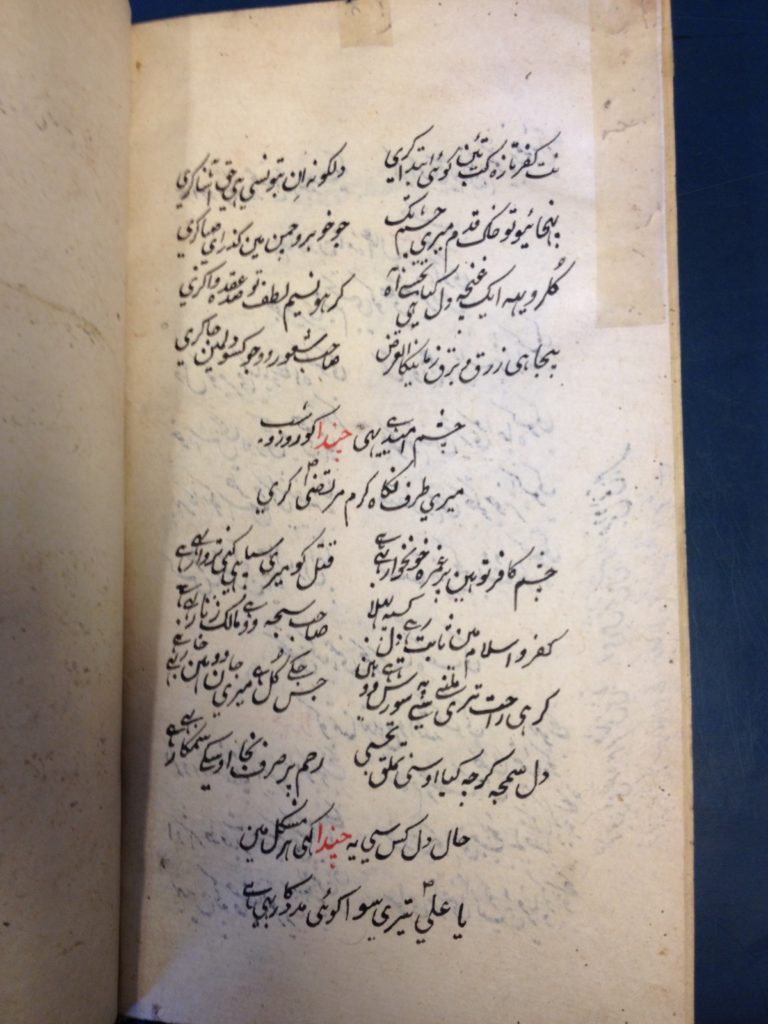

When God Is a Customer is a collection of Telugu erotic devotional poetry, mostly short lyrical poems called padams, translated into English. Poems attributed to Annamaya, Sarangapani, Rudrakhavi, one anonymous author, and most prominently, Ksetrayya were selected for translation.

Telugu padams were originally performed by professional dancers and musicians, such as devadasis, whose patrons included courts, temples, and wealthy men. Padams are highly erotic, mostly feature female speakers, and often illustrate lover’s quarrels, infidelity, sensual longing, and sulking; these romantic conflicts long served as a metaphor for humans devoting themselves to the divine.

From the Introduction: Questions to Guide Interpretation

“From its formative period in the seventh to ninth centuries onward, South Indian devotional poetry was permeated by erotic themes and images. In the Tamil poems of the Saiva Nayanmar and the Vaisnava Alvars, god appears frequently as a lover, in roles inherited from the more ancient Tamil love poetry of the so-called sangam period (the first centuries A.D.)….

A historical continuum stretches from these Tamil poets of devotion all the way to Ksetrayya and Sarangapani, a millennium later. The padam poets clearly draw on the vast cultural reserves of Tamil bhakti, in its institutional as well as its affective and personal forms. Their god, like that of the Tamil poet-devotees, is a deity both embodied in temple images and yet finally transcending these icons, and they sing to him with all the emotional and sensual intensity that so clearly characterizes the inner world of medieval South Indian Hinduism….

[A]nd perhaps the most conspicuous attribute of this refashioned cosmology is its powerful erotic colouring. As we seek to understand the import of the Telugu padams translated here, we need to ask: What is distinctive about the erotic imagination activated in these works? How do they relate to the earlier tradition of South Indian bhakti, with its conventional erotic components? What changes have taken place in the conceptualization of the deity, his human devotee, and the intimate relationship that binds them? Why this hypertrophy of overt eroticism, and what does it mean to love God in this way?” (9-10)

Interpreting the Padams: The Courtesan’s Role

This section briefly summarizes and interprets the courtesan figures in When God Is a Customer by rewording and condensing a portion of the book’s Introduction. In its entirety, the Introduction also explores the God-customers’ roles, situates the poems in their historical contexts, and assists readers in the act of reading by exploring padams’ traditional themes and structural elements. We highly recommend that interested scholars read the Introduction in full.

—

Intriguingly, most of the speakers and characters in the poems of When God Is a Customer are courtesans. They are strong-willed and can be self-possessed, often brazenly playing power games with their God-lovers in search of their fee. The book’s introduction examines one such courtesan in “The Madam to a Courtesan”, a poem by Ksetrayya, on pages 14-16. Here, readers see the God-customer Muvva Gopala/Lord Krishna hapless and awkward, wandering the streets of the courtesan colony, unable to find the courtesan he lusts for; she has taken his money, but not given him her address. An older courtesan, the speaker, chides her for her haughtiness:

Woman! He’s none other

than Cennudu of Palagiri.

Haven’t you heard?

He rules the worlds.

When he wanted you, you took his gold—

but couldn’t you tell him your address?

Some lover you are!

He’s hooked on you.

And he rules the worlds

I found him wandering the alleyways,

too shy to ask anyone.

I had to bring him home with me.

Would it have been such a crime

if you or your girls

had waited for him by the door?

You really think it’s enough

to get the money in your hand?

Can’t you tell who’s big, who’s small?

Who do you think he is? (14-15)

Like the courtesan spoken to in the excerpt above, many of When God Is a Customer’s speakers plainly lack wonderment at their God-lovers’ ruling powers: in an anonymous padam, a courtesan insists her God can “enter [her] house only if [he has] the money” (39), asserting some level of dominance; in “A Woman to Her Lover” by Ksetrayya (33), the lovers laugh as a pet parrot mimics the courtesan’s moans, then bemoan the morning for interrupting their lovemaking—a remarkably “down to earth” moment, given that Muvva Gopala “rules the worlds” (14).

As the introduction observes, a power dynamic that posits the courtesan speaker as having the upper hand against or being on an even playing field with the God figure reverses that which is commonly seen in earlier Tamil bhakti models of devotional poetry. An eighth-century bhakti by Nammalvar on page 10 serves as an example of such a model, imaging a powerless woman heart-wrenched by her god-lover’s all-consuming absence. Unable to sleep on a black, rainy night, she spends her hours resenting her heart, her “sins,” and her womanhood.

The tormenting, lonely, helpless atmosphere of Nammalvar’s work is a far cry from both the bright playfulness that so often colours the lovers’ conflicts in Ksetrayya’s poems and the physical unity—often through orgasm—that resolves them. Indeed, the figure of the courtesan, sensual and autonomous, allows for a type of devotional work that, as the book’s introduction observes, is concerned more with union than with separation:

It should now be clear why the courtesan appears as the major figure in this poetry of love. As an expressive vehicle for the manifold relations between devotee and deity, the courtesan offers rich possibilities. She is bold, unattached, free from the constraints of home and family. In some sense, she represents the possibility of choice and spontaneous affection, in opposition to the largely predetermined, and rather calculated, marital tie. She can also manipulate her customers to no small extent, as the devotee wishes and believes he can manipulate his god. But above all, the courtesan signals a particular kind of knowledge, one that achieved preeminence in the late medieval cultural order in South India. Bodily experience becomes a crucial mode of knowing, especially in this devotional context: the courtesan experiences her divine client by taking him physically into her body. (18)

Who is Ksetrayya?

A very interesting article by Harshita Mruthinti Kamath, “Ksetrayya: The making of a Telugu poet”, has called the popular and scholarly assumptions about the padam poet into question. Kamath argues that rather than a historical figure from the village of Muvva, Ksetrayya could be a literary persona constructed into a Telugu bhakti poet-saint through the course of three centuries of literary reform, and that rather than being written by a single male author, Ksetrayya’s poetry could be the work of multiple authors, including courtesans themselves.