Although it is over 30 years old, Frédérique Apffel Marglin’s work remains valuable and notable for her careful consideration of her limitations as a Western observer of the devadasi practice in the eastern Indian state of Orissa. In her introduction, she provides important historical background about British imperialism’s impact on the devadasi practice and their reputation, as well as a thoughtful description of how the gendered meanings of purity, impurity, auspiciousness, inauspiciousness, status, and lack of status appear to interact on the topic of devadasis. Throughout the book, she describes devadasis’ roles and reputation in the Puri royal court and in Indian society at large as they were prior to the reform movement that outlawed the devadasi practice.

Publisher’s Summary

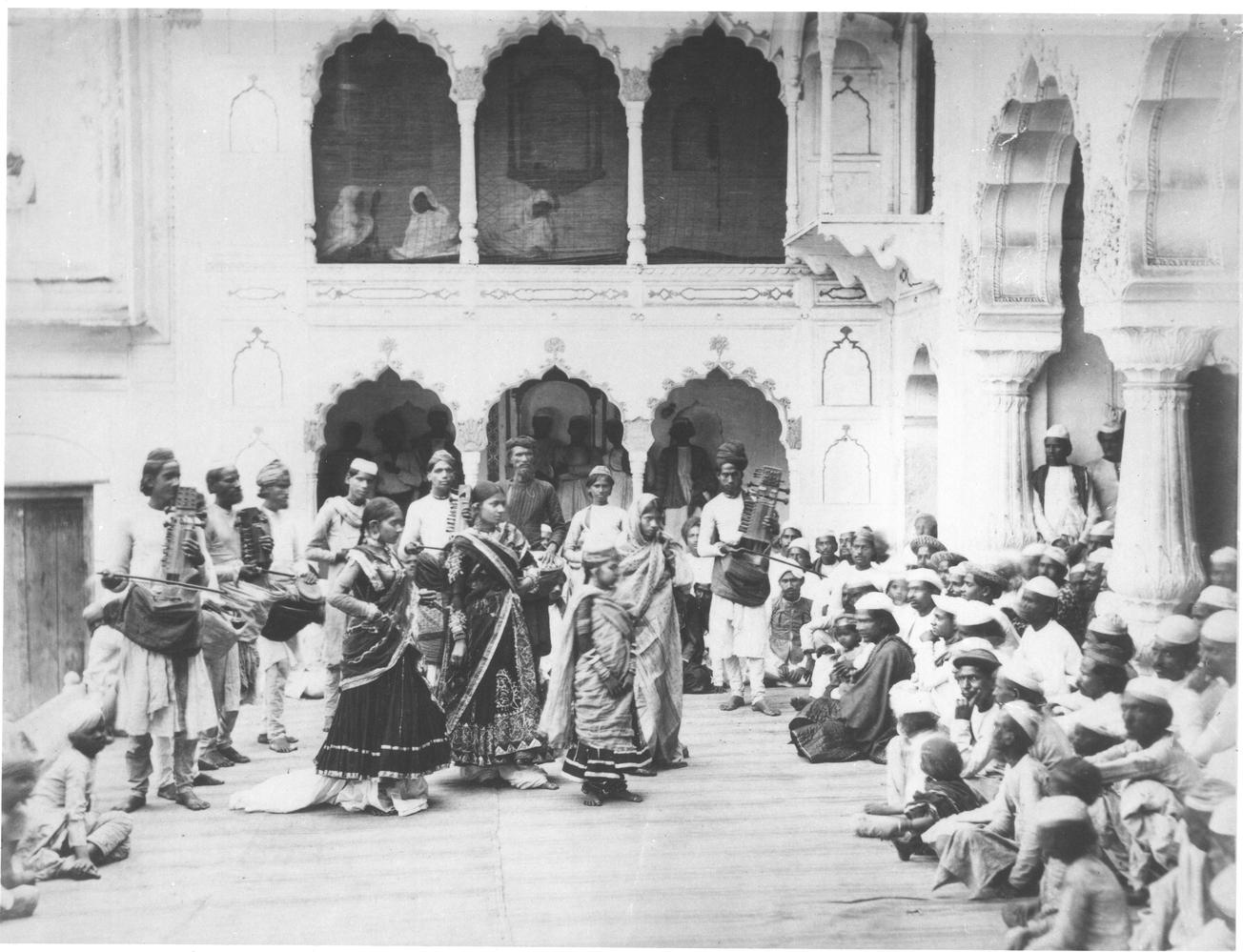

“Among the 1,500 devotees of the Hindu temple and cult of Jagannatha at Puri are a handful of women known as ‘devadasis’ or, literally, ‘female servants of the deity,’ who are associated with both chastity and concubinage and prostitution. This book focuses on the tension between the purity and impurity of the devadasis, and examines ideas about kingship, power, sexual purity, the role and status of women, and other central concerns of Hindu religious and cultural life that are associated with such rituals.”

Notable Quotes from the Introduction (1-24)

On Stereotypical Dualism: “Even though Abbé Dubois’s report is not lacking in ambivalence, the concluding line is a clear and forceful condemnation [of the devadasi practice]. The ambivalence expresses itself in the use of two kinds of terms; one set of terms are heavy with moral condemnation such as ‘loose’, ‘lews’, ‘stew’, ‘strumpets’, ‘obscene,’ … and another set of terms reveals a reluctant admiration such as ‘grace’, ‘elegant’, ‘attractive’… ‘graceful,’ ‘enchanting’. This mixture of the sinful and the sensuously beautiful is Europe’s classical recipe for the exotic. The devadasis, as can be imagined, were prime targets for an exotic one-sided imaginative reconstruction.”

On writers’ limited perspectives: “Because [this book] was conceived as a study of the rituals of the devadasis, it must be borne in mind that all these other concerns [such as women, goddesses, and kings] are dealt with as they arise out of a close attention to the practices of the devadasis. In other words, the perspective from which an observer views anything gives what she/he views a particular angle. I for one do not hold the position that an observer—however well-trained he or she might be—can find an Archimedean point from which to present a truly synoptic view. The view of any observer will be coloured by the perspective chosen, the point of entry, as well as by that observer’s predilections, blind spots, and other particularities.”

On the Indian cultural connotations of auspiciousness/purity/status: “The devadasis are called the ‘auspicious women’ (mangala nari) and they are the ones who sing the ‘auspicious songs’ (mangala gita). However, they are also never allowed into the inner sanctum of the temple, even though not only all the other ritual specialists but also the public at large is allowed into it at certain times of the day. This prohibition turns out to be linked with the devadasis’ status as courtesans and the impurity of sex. This tension between the auspiciousness and he impurity of the devadasis is the pivotal focus of this work…. The meanings of auspiciousness and inauspiciousness reveal themselves through the practices, often re-constructed, of the devadasis. What emerges rather quickly is that the categories of auspicious and inauspicious do not correspond to those of pure and impure….

Women are the harbingers of auspiciousness, a state which unlike purity does not speak of status or moral uprightness but of well-being and health or more generally of all that creates, promotes, and maintains life….

Status seems to be associated on the whole with masculinity and auspiciousness on the whole with femininity. The case of the devadasis who do not marry offers an ideal case study for the understanding of auspiciousness since it is here not intermingled with status…. Purity and impurity underlie the hierarchy of caste. Thus the disjunction between auspiciousness and status predictable correlates with the disjunction between auspiciousness and purity. The maleness of purity can perhaps be seen reflected in the term uses for ‘pure spirit’, namely purusa, a word which can also have the meaning of ‘male person.’….”