Introduction:

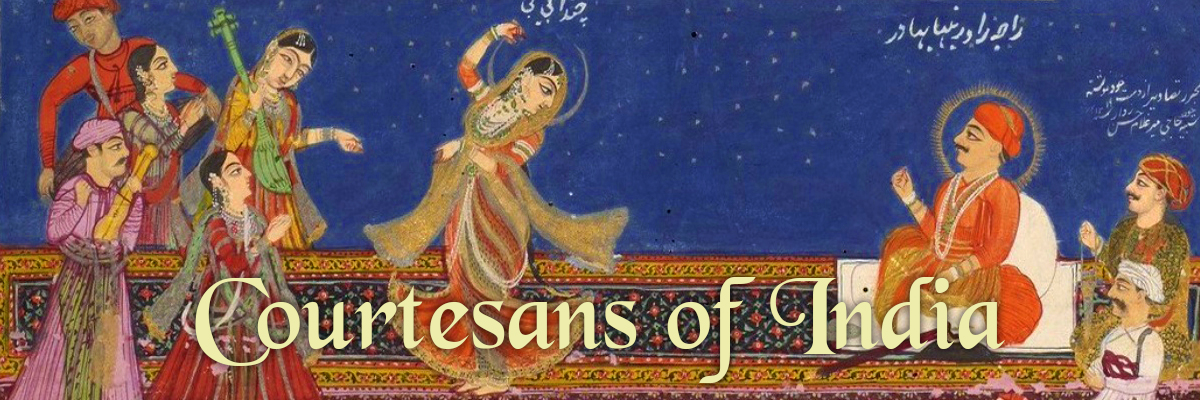

“Having been forced to dance in public as a courtesan, [Muni, the heroine of Hindi film Kismat] sees her situation as hopeless: ‘The world can turn a woman into a courtesan, but a courtesan can never become a woman.’ … Having been labelled tawaif, Muni can no longer hope for respectability; a happy ending—defined in the conventions of the Hindi cinema as the union of the heroine with the film’s hero—is no longer possible. Muni’s distinction between women and tawaifs is actually a distinction between the female character who, in the dictates of convention, is a respectable heroine (and therefore marriageable) and one who is a tawaif (and therefore not).”

In this article, Booth explores the traditional markers of heroines in Hindi cinema from the 1950s-1990s. As an introduction, he identifies an enormous list of these markers, including but not limited to the heroines’ chastity (as compared with her contradictory sexualized dancing), her honour of the hero’s parents, her level of assertiveness, and, most invariably, her marriage to the hero. Booth compares these markers to those of the Tawa’if cinematic roles both collectively and in specific films, analyzing how Tawa’if films attempted to explore and ameliorate cultural anxieties about gendered identity and sexuality. A Tawa’if, Booth observes, is at best often regarded as a “tragic heroine,” but not a traditional one.

Main Arguments:

Booth makes two specific arguments in his research, summarized below:

“First, based on some of the foundational theories of feminist and feminist film, critique, I argue that tawaifs are a distinct gender within the Indian narrative world and that the woman-tawaif transformation is not one way. The tawaif-woman transformation is also possible, as a number of films have demonstrated. Second, incorporating ideas from Indian folklore studies, I seek to demonstrate that, despite their superficially exploited images, tawaifs as protagonists are both heroic and masculine within the understandings of Indian folklore types. Throughout, I examine the narrative factors surrounding such gendered constructions and transformations and argue that these represent an unspoken form of social negotiation between film producer and consumer, that not only establish the gender specifics of the character, but that also allow such apparently transgressive characters to be redeemed.”