Nautch girls, Bombay

Source: ebay, Sept. 2007. Retrieved from columbia.edu.

Centering Devadasis and Tawaifs

Nautch girls, Bombay

Source: ebay, Sept. 2007. Retrieved from columbia.edu.

Nautch dancers in India, ca 1860-1870

Source: Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies and Leiden University Library). Retrieved via Wikimedia Commons.

Dancing Girl Photo from 1879

Source unknown. Retrieved via Wikimedia Commons

A photo probably by Bourne, from the 1860’s.

Source unknown, Retrieved via Wikimedia Commons

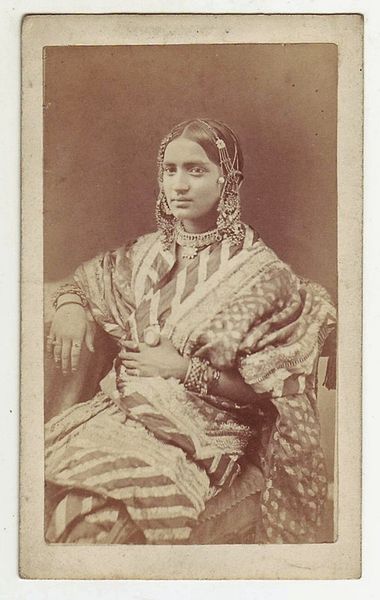

A Muslim Nautch girl in Jaipur

Source unknown. Retrieved via Wikimedia Commons

A group of dancing girls, a postcard photo, late 1800’s

Source unknown. Retrieved via Wikimedia Commons .

Publisher’s Description:

This is the first critical study of Kathak dance. The book traces two centuries of Kathak, from the colonial nautch dance to classical Kathak under nationalism and post-colonialism to transnationalism and globalization. Reorienting dance to focus on the lived experiences of dancers from a wide cross-section of society, the book narrates the history of Kathak from baijis and tawaifs to the global stage.

Summary

After a crime lord leaves a courtesan, Sultana, in the home of the unsuspecting Dawood and threatens to kill him if anything happens to her, Dawood must pretend she is his new bride. Dawood, who is forming a romance with a local author writing a book about a courtesan, must carefully conceal Sultana’s identity while avoiding unsavoury circumstances. Despite Dawood’s resistance, a romance develops, and the two must ensure Sultana’s escape from the crime lord and ensure a happy ending.

Questions to Consider

From the Introduction

“This chapter addresses three films – Bhumika (The Role; 1976); Mandi (Marketplace; 1983); and the eponymous Sardari Begum (1996)…. [A] continuity of interests and ideological investments link the … three films … including: each film’s focus on a female protagonist and subject; her conscious and unconscious efforts to emancipate herself from the debilitations of her gender, class, and caste oppression; and, finally, for the purposes of my argument, her function as a figure through whom women’s relationship to the hegemonic values and ideological agendas of the Indian nation- in-the- making are assessed and interrogated. The nation remains, then, a salient frame of reference for grasping the ideological investments of these Benegal films….

The performing women… represent professions, identities, and cultural repertoires that flourished under, and were indelibly associated with, a feudal order, but which were delegitimized, marginalized, even excised from the self-definitions and constitutive narratives of the new Indian nation. “Women performers,” Singh notes, “were kept out of the frame of the nation in the making” (see epigraph; 2007: 94). By focusing on protagonists who belong to professions and identities that are devalued and marginalized in the new Indian nation, these three later films, I argue, “unsettle” (Singh’s term) the processes through which the Indian nation constituted itself, thereby also unsettling an unambiguously negative assessment of feudal social and cultural arrangements. Thus, [these] films undertake a more fundamental interrogation regarding India’s nation- formation itself – what the nation deliberately excludes in order to become a nation.

From Temple University Press:

A groundbreaking book that seeks to understand dance as labor, Sweating Saris examines dancers not just as aesthetic bodies but as transnational migrant workers and wage earners who negotiate citizenship and gender issues.

Srinivasan merges ethnography, history, critical race theory, performance and post-colonial studies among other disciplines to investigate the embodied experience of Indian dance. The dancers’ sweat stained and soaked sari, the aching limbs are emblematic of global circulations of labor, bodies, capital, and industrial goods. Thus the sweating sari of the dancer stands in for her unrecognized labor.

Srinivasan shifts away from the usual emphasis on Indian women dancers as culture bearers of the Indian nation. She asks us to reframe the movements of late nineteenth century transnational Nautch Indian dancers to the foremother of modern dance Ruth St. Denis in the early twentieth century to contemporary teenage dancers in Southern California, proposing a transformative theory of dance, gendered-labor, and citizenship that is far-reaching.

Two Indian Nautch Girls with Musicians

Retrieved via Wikimedia Commons

Nautch Girls, Kashmir

Retrieved via Wikimedia Commons

Kashmir Dancing Girl

Retrieved via Wikimedia Commons

Nautch Dancing Girls

Retrieved via Wikimedia Commons

A Studio Photo of Dancing Girl

Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons

A Nautch, Native Dancers at Nizugapatahi Coast of Coromandel East Indies

Retrieved from The British Museum

A Patna Nautch

Retrieved from The British Museum

Nautch Girls, Hyderabad; 1860s

From Hooper and Western, via Wikimedia Commons

Nautch Girls, Kashmir, c. 1870

From Samuel Borne, via Wikimedia Commons

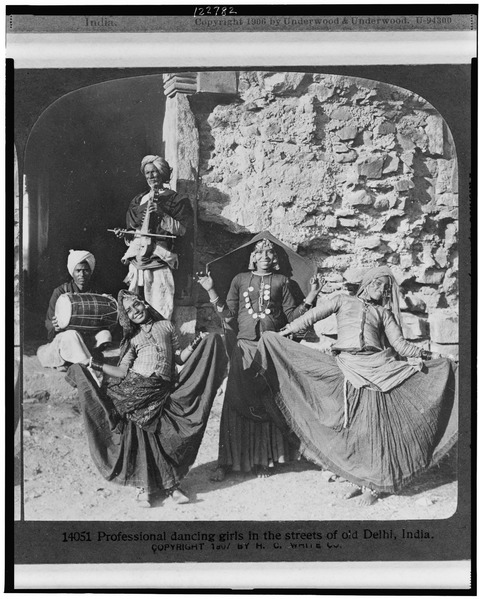

Professional dancing girls in the streets of old Delhi, India

By H.C. White Co., via Wikimedia Commons

Three Nautch Girls Dancing in Costume

By Charles Shepherd [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Tamil nautch (dancing girl) (c. 1910)

Published by Hutchinson & Co, London, taken via Wikimedia Commons

Access this photo at the Digital South Asia Library.

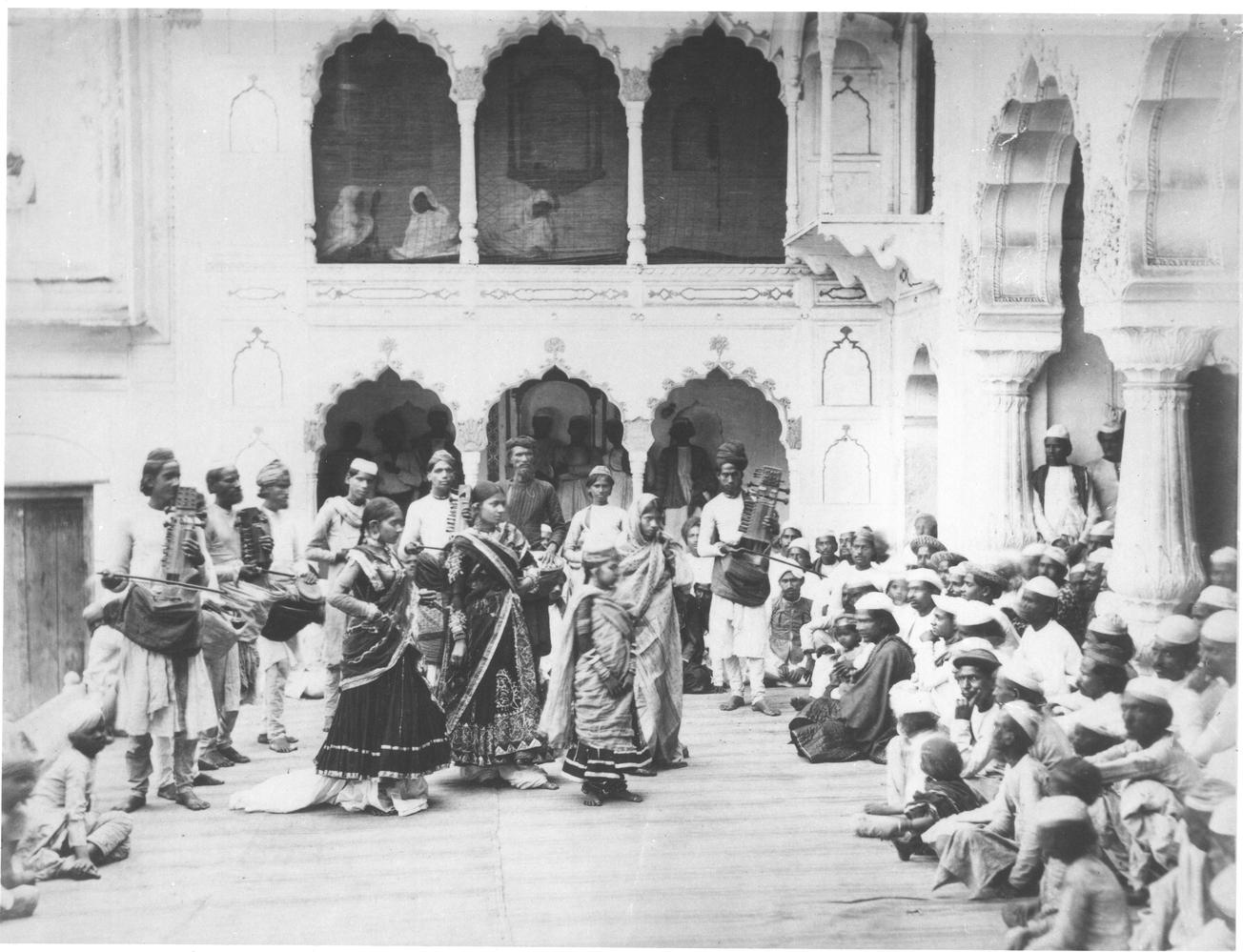

Native Nautch at Delhi [or Shalimar?], 1864

Collection Title: India – Groups, 1874.

Shelfmark: Photo 28/2(15)

Copy Negative Number: B.8862

Photographer’s number: 606

In this 2002 film adaptation of the 1917 novel of the same name, the protagonist Devdas is about to return home after 10 years of law school in England. Devdas’s mother, Kaushalya Mukherjee, tells her poor neighbour Sumitra, who is overjoyed. Sumitra’s daughter Paro and Devdas are loving childhood friends. Both families believe Devdas and Paro will get married, but Devdas’s conniving sister-in-law reminds Devdas’s mother, Kaushalya of Paro’s “inappropriate” maternal lineage of nautch girls.

Heartbroken by his family’s rejection of Paro, Devdas leaves his parents’ house and takes refuge at a brothel, where he becomes an alcoholic and where a good-hearted tawaif named Chandramukhi falls in love with him. Eventually he becomes desperate to return to Paro, but a number of tribulations stand in the way of Devdas, Paro, and Chandramukhi’s ideals.

Notable Elements

Questions to consider:

Cover image from oupcanada.com

From the introduction: “In [this essay], I examine how a group of North India’s tawa’if (courtesans-low-status professional women musicians and dancers) are adapting to changing musical patronage in the twenty-first century, using their music and dance as a tool for empowerment. Juxtaposing ethnographic accounts with qualitative analysis of performance practices and oral narratives of several professional women musicians and a few men who hail from provincial cities and towns in eastern Uttar Pradesh and western Bihar, I open up exploration of a number of issues….

The English word ‘courtesan’ fails to capture the diversity of this community in South Asia, which runs the gamut from highly trained and refined court musicians/dancers/poets to street performers who entertain at festivals and weddings, instead creating a discursive stereotyping or ‘totalizing’…. One of the aims of this essay is to unpack the terms ‘courtesan’ and ‘prostitute’ and notions about them through an ethnography of the performance process and event as well as narratives about (and by) the performance, the performers, and the patrons. Another is to examine the relations of production among the performers and the Guria administration, in particular Ajeet Singh. In doing so, I open up the question, albeit in a preliminary way, of how the cultural integrity of the ‘courtesan tradition,’ identified through its continued cultivation and renewal of a body of repertory and performance practices consisting of a variety of genres that originate from several historical points (feudal, colonial, post-feudal, and postcolonial), may be challenged in the Guria frame by expectations of authenticity and/or respectability informed by dominant Indian middle-class values.”

Notes

From the introduction: “This study of the devadasi institution was undertaken with a two-fold purpose. First, it was an attempt to understand the relationship, and shifts in it, among women, religion and the state in pre-colonial and colonial south India. The second purpose was to try and disentangle this complex process, specifically to see how far the projects of colonialism, reform and revival were based on an understanding of the material reality of the practice.”

Abstract: Photo shows a female dancer standing between two musicians, one with drums and the other with a stringed instrument. Physical description: 1 photographic print.

Notes: Title from caption card and item.; Forms part of: Frank and Frances Carpenter Collection (Library of Congress).; No. 216.; LOT subdivision subject: India.

By Frank and Frances Carpenter Collection [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

In this essay, Srinivasan suggests that paying attention to nineteenth century transnational Indian women performers as temporary, cultural laborers in the US reveals the ambiguities of immigration law and citizenship. Srinivasan takes the crucial performances and experiences of the 1881 Indian Nautch Dancers who arrived on New York Stages to perform in Augustin Daly’s show ‘‘Zanina’’ to examine discrimination, anti-Asian sentiment, and exclusion laws long before the oft-cited 1923 court case that de-naturalized Indians from US citizenship. Srinivasan argues that attending to Indian women’s performances in the nineteenth century offers gendered insight into exclusion laws and demonstrates their ambiguity in ways that focusing on Asian male laborers (as has been the predominant focus of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century research on Asian labor) alone occludes.

Abstract

The hereditary women performers of north India, called ‘nautch girls’ by the colonial British, and courtesans or tawa’ifs by today’s scholars, played a central role in the performance of music and dance in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Substantial recent scholarship has focused on their songs, poems and cultural history; consequently, this article addresses choreography, the missing part of their performance practice. Through a detailed examination of dance descriptions in nineteenth-century treatises and comparison of this material with colonial iconography and travel writings, Walker offers new research about nineteenth-century female performance, placing its practice in historical context and speculating about its evolution and change.

Notes

Wallace examines the early 20th- century missionary and writer Amy Wilson Carmichael, focusing on her 1909 book Lotus Buds, an account of Carmichael’s “rescue work” in South India. Wallace describes her article as “an attempt to understand the historical conditions which made the 1909 publication of Lotus Buds both possible in terms of its format and allowable in terms of its content.” She is heavily critical of Carmichael’s “rescue work,” characterizing it as the abduction of the young and vulnerable. Wallace’s article describes imperial representations of devadasis and the concept of the “nautch girl” and how Carmichael’s work reflects and utilizes colonial narratives of India to establish and justify her actions.