From the abstract: “The paper purports to study the changing contexts of the thumri, a form of light vocal music that was the mainstay of the tawaifs and other courtesan communities of nineteenth century North India. The paper, through a critique of the scholarship on the performing arts, calls for a more serious engagement with the cultural practices of hereditary women performers, one that acknowledges the impact of technological renovation and the emergence of music institutions on the performance practices of the courtesans. More importantly, it charts the evolution of the musical form of thumri as an indispensable part of the repertoire of Kathak in the decades following the independence, to show how it was significantly influenced by the New Media that altered both its content and structure. The emergence of identifiably distinct repertoires of performance embodied in the gharanas of dance in this period and their appropriation of thumri as part of their articulation of a distinct aesthetic are explored as parallel concerns in the paper.”

Tag: tawaif

Thoban, Sitara. “Locating the Tawa’if Courtesan-Dancer: Cinematic Constructions of Religion and Nation.” Journal of Religion and Popular Culture, 2021.

From the article: “The development of the Hindi/Urdu cinema is intimately connected to the history of artistic performance in India in two important ways. Not only did hereditary music and dance practitioners play key roles in building this cinema, representations of these performers and their practices have been, and continue to be, the subject of Indian film narratives, genres, and tropes. I begin with this history in order to explore the Muslim religio-cultural and artistic inheritance that informs Hindi/Urdu cinema, as well as examine how this heritage has been incorporated into the cinematic narratives that help construct distinct gendered, religious, and national identities. My specific focus is on the figure of the tawaif dancer, often equated with North Indian culture and nautch dance performance. Analyzing the ways in which traces of the tawa’if appear in two recent films, Dedh Ishqiya and Begum Jaan, I show how this figure is placed in a larger representational regime that sustains nationalist formations of contemporary Indian identity. As I demonstrate, even in the most blatant attempts to define the Indian nation as “Hindu,” the “Muslimness” of the tawaiif—and by extension the cinema she informed in ways both real and representational—is far from relinquished. The figure of the “Indian” dancer—manifested variously in the image of the devadasi, the tawa’if, and the bayadère—has long captured imaginations on both sides of the colonial divide. Although often conflated under the catch-all category of nautch, these different incarnations also encode notions of religio-cultural difference, particularly in the wake of the calcification of religious boundaries in modern South Asia. I explore the homogenization of the figure of the nautch dancer in other forms of cultural production elsewhere, but in this paper, I wish to focus specifically on representations of the tawaif in “Indian” cinema, and their relation to the construction of specific national subjectivities. While the question remains as to how such a “national” cinema should be defined given the history of British imperialism in India, the subsequent Partition of the subcontinent, the postcolonial resurgence of Hindu nationalism, and the contemporary globalization of the Hindi film industry, I show below how the very instability of the “national” is assuaged by this cinema’s contribution to the ongoing process of nation formation. Focusing attention on the role the tawaif is made to play in this project of stabilization, the outlines of the “nation” are brought into sharp relief.”

Malhotra, Anshu. “Telling Her Tale? Unravelling a Life in Conflict in Peero’s Ik Sau Saṭh Kāfiaṅ. (one Hundred and Sixty Kafis).” The Indian Economic and Social History Review, vol. 46, no. 4, SAGE Publications, 2009, pp. 541–78, doi:10.1177/001946460904600403.

Abstract:

This article explores the manner in which Peero, a denizen of nineteenth century Punjab, in her 160 Kafis tries to communicate aspects of her own story and life through the diverse cultural resources at her command. The questions of self-representation and self-fashioning are central to this text, and Peero speaks of certain events in her life by relating sagas and evoking moods familiar in the cultural landscape of Punjab. Peero, self-confessedly a prostitute, and a Muslim, came to live in the middle of the nineteenth century in the Gulabdasi dera, a nominally ‘Sikh’ sect. This remarkable move, and her relationship with Guru Gulab Das, probably generated discord that pushed Peero into inserting her ‘self’ into the 160 Kafis. An attempt is made to read Peero’s crafting of her story, along with her silences, and bring out the nuances embedded in her text. The article also examines why Peero writes of her personal trauma and experience in the language of religious conflict between the ‘Hindus’ and the ‘Turaks’. This was particularly surprising as the Gulabdasi dera displayed eclecticism in its philosophical choices, and imbibed radical aspects of Vedantic monism. It also borrowed freely from hybrid religious sources including rhetoric familiar within the Bhakti movement, and the Punjabi Sufis’ anti-establishment mien.

Abstract from Sage Journals This paper also includes translations of the poems discussed and as such has been indicated as both a primary and a secondary source.

Malhotra, Anshu. “Performing a Persona: Reading Piro’s Kafis.” Speaking of the Self: Gender, Performance, and Autobiography in South Asia. Anshu Malhotra & Siobhan Lambert-Hurley, Editors. Duke University Press, 2015. doi.org/10.1215/9780822374978-009.

Abstract: This chapter unravels Piro’s 160 Kafis to show how a former Muslim prostitute, and then a novitiate in a marginally Sikh Gulabdasi establishment, fashioned a self by writing “autobiographical” verses. The transgression of her move from a brothel to a monastic establishment created a situation that pushed Piro into recounting the particular incident that she perceived as transformative in her life. She used her writing to justify her presence in the establishment and her closeness to her guru. The chapter unpacks the meanings of her metaphorical language, what she says, what she leaves unsaid, and what she merely suggests. The meanings of Piro’s obsessive invoking of Hindu-Muslim conflict is sought to be understood, and her recourse to and creative use of diverse Punjabi cultural imaginary is demonstrated. The cultural eclecticism of her sect and her writing, with its borrowings from Vedantic monism, Sikh inheritance, Punjabi Sufis’ antiauthority moods, and Bhakti devotion is delineated.

Abstract from Duke University Books. This paper also includes translations of the poems discussed and as such has been indicated as both a primary and a secondary source.

Shah, Hasan. The Dancing Girl. Translated by Qurratulain Hyder. New Directions, 1993.

Google Books Description

Written in 1790, Hasan Shah’s autobiographical romance, The Dancing Girl, is remarkable for both its lyrical prose and its fine recreation of a time, a place, and a culture – India in the 1780s, a tolerant, affable era before the full establishment of British colonial rule. The Dancing Girl tells of the doomed love of Hasan Shah (aide-de-camp to a British officer) and Khanum Jan (a courageous and gifted dancer of the courtesan caste) whose secret marriage could not prevent their separation. At Khanum Jan’s death, her grief-stricken husband turned his raw emotion into a surprisingly modern, first-person narrative “without realizing,” as leading Urdu novelist Qurratulain Hyder observes in the foreword to her translation (from the 1893 Urdu translation of the original Persian), “that he had become a pioneer of the modern Indian novel.”

Dewan, Saba. Tawaifnama. Context, 2019.

Summary from the New India Foundation

This is a history, a multi-generational chronicle of one family of well-known tawaifs with roots in Banaras and Bhabua. Through their stories and self-histories, Saba Dewan explores the nuances that conventional narratives have erased, papered over or wilfully rewritten.

In a not-so-distant past, tawaifs played a crucial role in the social and cultural life of northern India. They were skilled singers and dancers, and also companions and lovers to men from the local elite. It is from the art practice of tawaifs that kathak evolved and the purab ang thumri singing of Banaras was born. At a time when women were denied access to the letters, tawaifs had a grounding in literature and politics, and their kothas were centres of cultural refinement.

Yet, as affluent and powerful as they were, tawaifs were marked by the stigma of being women in the public gaze, accessible to all. In the colonial and nationalist discourse of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, this stigma deepened into criminalisation and the violent dismantling of a community. Tawaifnama is the story of that process of change, a nuanced and powerful microhistory set against the sweep of Indian history.

Amar Prem. Directed by Shakti Samanta, performances by Sharmila Tagore, Rajesh Khanna, Vinod Mehra, Abhi Bhattacharya, Madan Puri, Shakti Films, 1972.

Summary: A village woman, Pushpa, is thrown out by her husband and his new wife. Pushpa is abandoned by her mother and sold into a Calcutta brothel by her village-uncle. During her time there Pushpa attachments with a local businessman who becomes a regular and exclusive visitor, and her widowed neighbour’s young son.

Abbas, Ghulam. “Anandi.” Translated by G.A. Chaussée. The Annual of Urdu Studies. Department of Languages and Cultures of Asia, University of Wisconsin–Madison, 2003, https://minds.wisconsin.edu/handle/1793/18349.

This story is available for free online through the University of Wisconsin’s digital library. In ‘Anandi’, Ghulam Abbas dissects the hypocrisy of a society that hides behind a facade of self-righteousness but derives secret pleasures from what it declares taboo. Summary from Desi Writer’s Lounge.

Kapil, Pandhey. Phoolsunghi. Translated by Gautam Choubey. Penguin, 2020.

This novel is an English translation of of Pandhey Kapil’s 1977 Bhojpuri novel of the same name.

Publisher‘s Summary

‘Babu Sahib! You must have heard of a phoolsunghi—the flower-pecker—yes? It can never be held captive in a cage. It sucks nectar from a flower and then flies on to the next.’

When Dhelabai, the most popular tawaif of Muzaffarpur, slights Babu Haliwant Sahay, a powerful zamindar from Chappra, he resolves to build a cage that would trap her forever. Thus, the elusive phoolsunghi is trapped within the four walls of the Red Mansion.

Forgetting the past, Dhelabai begins a new life of luxury, comfort, and respect. One day, she hears the soulful voice of Mahendra Misir and loses her heart to him. Mahendra too, feels for her deeply, but the lovers must bear the brunt of circumstances and their own actions which repeatedly pull them apart.

The first ever translation of a Bhojpuri novel into English, Phoolsunghi transports readers to a forgotten world filled with mujras and mehfils, court cases and counterfeit currency, and the crashing waves of the River Saryu.

Chattopadhyay, Sarat Chandra. Devdas. GCS, 30 June 1917.

The novella Devdas is enormously famous, having spawned numerous film, TV, and theatrical adaptations.

Complete Plot Summary (from Wikipedia)

Devdas is a young man from a wealthy Bengali Brahmin family in India in the early 1900s. Parvati (Paro) is a young woman from a middle class Bengali Brahmin family. The two families live in a village called Taalshonapur in Bengal, and Devdas and Parvati are childhood friends.

Devdas goes away for a couple of years to live and study in the city of Calcutta (now Kolkata). During vacations, he returns to his village. Suddenly both realise that their easy comfort in each other’s innocent comradeship has changed to something deeper. Devdas sees that Parvati is no longer the small girl he knew. Parvati looks forward to their childhood love blossoming into a happy lifelong journey in marriage. According to prevailing social custom, Parvati’s parents would have to approach Devdas’s parents and propose marriage of Parvati to Devdas as Parvati longs for.

Parvati’s mother approaches Devdas’s mother, Harimati, with a marriage proposal. Although Devdas’s mother loves Parvati very much she isn’t so keen on forming an alliance with the family next door. Besides, Parvati’s family has a long-standing tradition of accepting dowry from the groom’s family for marriage rather than sending dowry with the bride. The alternative family tradition of Parvati’s family influences Devdas’s mother’s decision not to consider Parvati as Devdas’ bride, especially as Parvati belongs to a trading (becha -kena chottoghor) lower family. The “trading” label is applied in context of the marriage custom followed by Parvati’s family. Devdas’s father, Narayan Mukherjee, who also loves Parvati, does not want Devdas to get married so early in life and isn’t keen on the alliance. Parvati’s father, Nilkantha Chakravarti, feeling insulted at the rejection, finds an even richer husband for Parvati.

When Parvati learns of her planned marriage, she stealthily meets Devdas at night, desperately believing that he will accept her hand in marriage. Devdas has never previously considered Parvati as his would-be wife. Surprised by Parvati’s boldly visiting him alone at night, he also feels pained for her. Making up his mind, he tells his father he wants to marry Parvati. Devdas’s father disagrees.

In a confused state, Devdas flees to Calcutta. From there, he writes a letter to Parvati, saying that they should simply continue only as friends. Within days, however, he realizes that he should have been bolder. He goes back to his village and tells Parvati that he is ready to do anything needed to save their love.

By now, Parvati’s marriage plans are in an advanced stage. She refuses to go back to Devdas and chides him for his cowardice and vacillation. She, however requests Devdas to come and see her before she dies. He vows to do so.

Devdas goes back to Calcutta and Parvati is married off to the widower, Bhuvan Choudhuri, who has three children. An elderly gentleman and zamindar of Hatipota he had found his house and home so empty and lustreless after his wife’s death, that he decided to marry again. After marrying Parvati, he spent most of his day in Pujas and looking after the zamindari.

In Calcutta, Devdas’s carousing friend, Chunni Lal, introduces him to a courtesan named Chandramukhi. Devdas takes to heavy drinking at the courtesan’s place; she falls in love with him, and looks after him. His health deteriorates through excessive drinking and despair – a drawn-out form of suicide. In his mind, he frequently compares Parvati and Chandramukhi. Strangely he feels betrayed by Parvati, though it was she who had loved him first, and confessed her love for him. Chandramukhi knows and tells him how things had really happened. This makes Devdas, when sober, hate and loathe her very presence. He drinks more and more to forget his plight. Chandramukhi sees it all happen, suffering silently. She senses the real man behind the fallen, aimless Devdas he has become and can’t help but love him.

Knowing death approaches him fast, Devdas goes to Hatipota to meet Parvati to fulfill his vow. He dies at her doorstep on a dark, cold night. On hearing of his death, Parvati runs towards the door, but her family members prevent her from stepping out of the house.

The novella powerfully depicts the customs of society that prevailed in Bengal in the early 1900s, which largely prevented a happy ending to a true and tender love story.

Shah, Vidya. Jalsa: Indian Women and Their Journeys from the Salon to the Studio. Tulika, 2016.

Publisher’s Summary

Jalsa takes the reader through the journeys of women performers in India from the salon to the studio. It attempts to give insight into and a perspective on the beginning of the interface of technology and entertainment, and the irreversible impact this has had on how we listen to, enjoy, and consume music. It acknowledges an important slice of the history of Indian music, which is celebrated the world over today in its many forms and avatars.

Notes

Our readers may be interested to know that Jalsa explores the stories of several individual, named courtesans. Included among these are tawaif and renowned singer Jaddan Bai, who went on to establish one of India’s first film production companies, Sangeet Movietone, in 1934, and Janki Bai, an enormously famous singer. Shah writes: “It is said that roads leading to the record shops would get blocked by lovers of her music whenever a new stock of discs arrived. Many of her records sold over 25,000 copies, something unheard of till then even for highly accomplished singers of her time.”

Karmali, Sikeena. The Mulberry Courtesan. Aleph, 2018.

Publisher‘s Summary

In 1857, the shadows are falling thick and fast on what is left of the Mughal empire. The last emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar, is a broken, bitter man in his eighties who has retreated into religion and poetry. Zafar’s empire extends no further than the precincts of his grand palace, the Red Fort in Delhi, but this hasn’t prevented numerous court intrigues and conspiracies from flourishing within the Lal Qila; these involve the emperor’s wives, children, courtiers, hangers-on, and English functionaries among others. Flung into this poison pit is Laale, a young woman from an Afghan noble family, abducted from her home in the mountains and sold into the Mughal emperor’s court as a courtesan. Fiery, independent and beautiful, the ‘mulberry courtesan’ captures the ageing emperor’s heart, giving him hope and happiness in his last years.

Told against the backdrop of India’s great revolt of 1857, and the last days of the Mughal empire, The Mulberry Courtesan is an epic tale of romance, tragedy, courage and adventure.

“160 Kafis.” Accessing Muslim Lives. Accessed 9 March 2021.

This webpage is available to read for free online.

The “160 Kafis” page on Accessing Muslim Lives offers a small selection of poems by Piro, a 19th-century poet and courtesan-turned-religious devotee, which have been gathered from Piro’s autobiographical poetry book titled 160 Kafis, translated by Anshu Malhotra, and annotated by the unnamed author of the webpage. These poems offer a rare opportunity for readers to access Piro’s work for free.

Although technically not a high-class tawaif, Piro was nevertheless a courtesan who was possibly sought after on the fringes of the Lahore court (see page 1509 of “Bhakti and the Gendered Self” by Anshu Malhotra.) Malhotra summarizes the content and purpose of Piro’s book as follows in her chapter, “Performing a Persona: Reading Piro’s Kafis”, which appears in Speaking of the Self: Gender, Performance, and Autobiography in South Asia:

The 160 Kafis is not the usual compilation of philosophical ruminations, homilies on moral living, or advice on adopting an uncluttered life of devotion that one may expect from a text produced in a religious establishment, and one that purportedly borrows from Bhakti, and even Sufi ethics. It is a text constructed with a specific and limited agenda—to elucidate Piro’s move from a brothel to a religious establishment, and lay to rest the misgivings of those opposed to it. The process of its composition may have helped Piro understand and digest what she made of her unusual move. It also allowed her to explain, justify, and popularize her version of the events, besides scotching the egre¬ gious rumors that followed in the wake of her unprecedented move that not only touched her, but cast aspersions on her guru. The personal tone of Piros 160 Kafis can be further gleaned from her preoccupation with noting, indeed emphasizing, the acrimonious relations between “Hindus” (inclusive of Sikhs) and “Turaks,” a theme around which she frames her own story of flight and asylum.

(206)

Mandi. Directed by Shyam Benegal, performances by Smita Patil, Naseeruddin Shah, Kulbhushan Kharbanda, Shabana Azmi, and Amrish Puri, Blaze Entertainment, 1983.

Summary: This film is a satirical comedy which looks at politics and prostitution. Based on a classic Urdu short story Aanandi by writer Ghulam Abbas, the film narrates the story of a brothel, situated in the heart of a city, an area that some politicians want for its prime locality.

Summary from Wikipedia.

Schofield, Katherine, narrator. “A Bloody Difficult Woman: Mayalee Dancing Girl vs. the East India Company.” Histories of the Ephemeral, season 1, episode 2, 25 November 2018, www. listennotes.com/podcasts/histories-of-the/a-bloody-difficult-woman-V9Rb3-Wl2FL/. Accessed February 12, 2021.

This podcast is available free online through Listen Notes.

Summary: In this episode Schofield considers why Indian musicians and especially courtesans appear at all in the official records of the East India Company, and what this tells us about relations between the British colonial state and the Indian peoples whose worlds it was increasingly encroaching upon during the 1830s and 40s.

Schofield, Katherine, narrator. “The Courtesan and the Memsahib: Khanum Jan Meets Sophia Plowden at the 18C Court of Lucknow.” Histories of the Ephemeral, season 1, episode 1, 1 June 2018, www.listennotes. com/podcasts/histories-of-the/the-courtesan-and-the-vgSefIpYJCA/. Accessed February 12, 2021.

This podcast is available free online through Listen Notes.

Summary: This episode explores the musical history of Khanum Jan. Khanum Jan was a celebrity courtesan in the cantonment of Kanpur and the court of Asafuddaula of Lucknow in 1780s North India. Famed then for her virtuosic singing, dancing, and speaking eyes, Khanum became famous again in the twentieth century because of her close musical interactions with a remarkable Englishwoman, Sophia Plowden.

Vanita, Ruth. Memory of Light. Penguin, 2020.

Summary

Preparations for King George the Third’s fiftieth birthday gala are in full swing in Lucknow. As poets and performers vie to be part of the show, Chapla Bai, a dazzling courtesan from Kashi, briefly enters this competitive world, and sweeps the poet Nafis Bai off her feet. An irresistible passion takes root, expanding and contracting like a wave of light. Over two summers, aided by Nafis’s friends, the poets Insha and Rangin, and Sharad, himself in love with a man, they exchange letters and verses, feeding each other the heady fruit of desire. When Chapla leaves for home, they part with the dream of building a life together. Can their relationship survive the distances?

From publisher’s website.

Narayan, R.K. The Man-Eater of Malgudi. Penguin, 1961.

Summary

This is the story of Nataraj, who earns his living as a printer in the little world of Malgudi, an imaginary town in South India. Nataraj and his close friends, a poet and a journalist, find their congenial days disturbed when Vasu, a powerful taxidermist, moves in with his stuffed hyenas and pythons, and brings his dancing-women up the printer’s private stairs. When Vasu, in search of larger game, threatens the life of a temple elephant that Nataraj has befriended, complications ensue that are both laughable and tragic.

Summary from Goodreads.

Narayan, R.K. The Guide. Penguin, 1958.

Summary: Formerly India’s most corrupt tourist guide, Raju—just released from prison—seeks refuge in an abandoned temple. Mistaken for a holy man, he plays the part and succeeds so well that God himself intervenes to put Raju’s newfound sanctity to the test.

Summary from BookFrom.net

Sengupta, Nandini. The King Within. Harper Collins, 2017.

Summary

373 AD. In the thick forests of Malwa, an enigmatic stranger gallops into an ambush attack by bandits to rescue a young courtesan, Darshini. His name is Deva and he is the younger son of Emperor Samudragupta. That chance encounter, first with Deva and later with his two friends, the loyal general Saba Virasena and the great poet Kalidas, forges a bond that lasts a lifetime. From a dispossessed prince, Deva goes on to become one of the greatest monarchs in ancient India, Chandragupta Vikramaditya. But the search for glory comes with a blood price. As Chandragupta the emperor sets aside Deva the brother, lover and friend, to build a glorious destiny for himself, his companions go from being his biggest champions to his harshest critics.

Summary from author’s website.

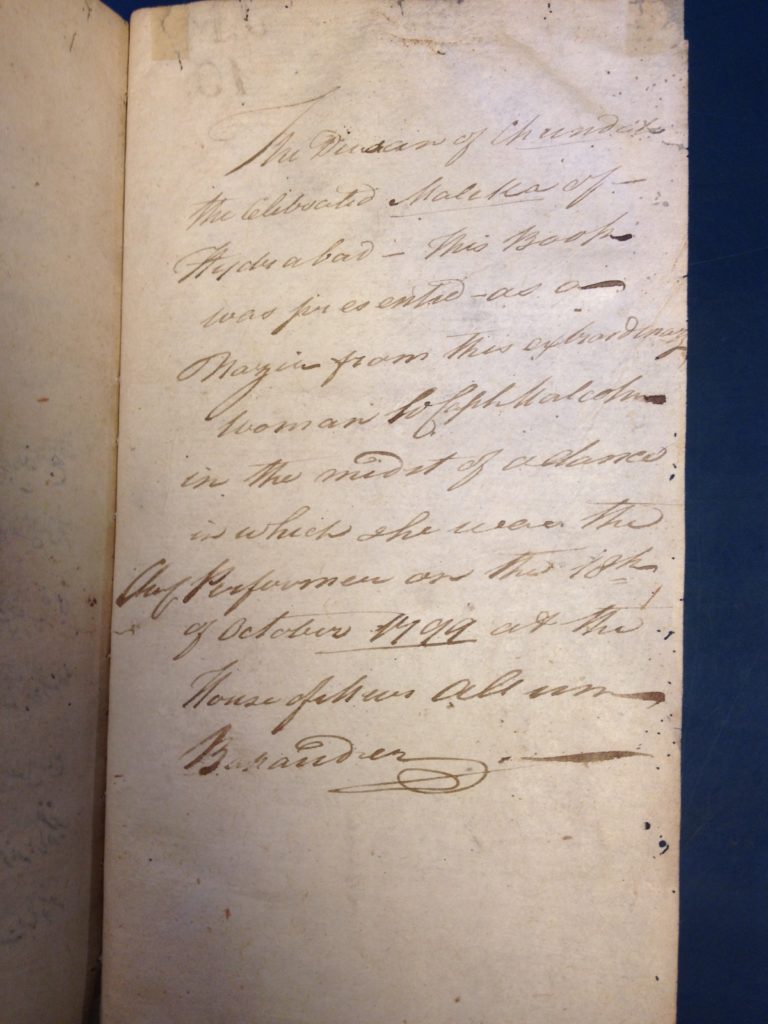

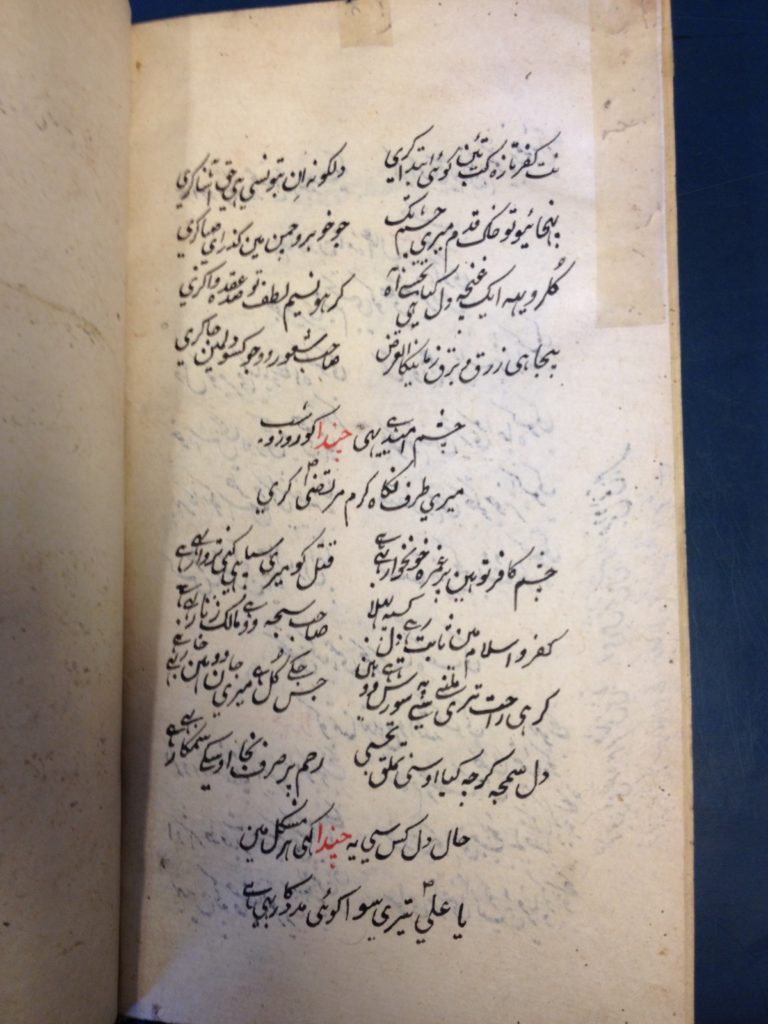

@BLAsia_Africa. “Divan of Chanda, copy presented by author to John Malcolm in 1799 (IO Islamic 2768).” Twitter, 19 April 2017, 5:41 a.m.

This tweet contains photographs of the British Museum’s copy of famed tawaif Mah Laqa Bai’s Divan of Chanda (called Diwan e Chanda in Urdu). Divan of Chanda is a manuscript collection of Mah Laqa’s 125 Ghazals, compiled and calligraphed by her in 1798. The photographs are credited to Sufinama, a web-based archive of Sufi poetry, and William Dalrymple, a historian.

Sachdeva Jha, Schweta. “Tawa’if as Poet and Patron: Rethinking Women’s Self-Representation.” Speaking of the Self : Gender, Performance, and Autobiography in South Asia, edited by Anshu Malhotra and Siobhan Lambert-Hurley, Duke University Press, 2015, pp. 141-164.

Abstract

This chapter addresses the issue of women and self-representation through the life of a wealthy courtesan and tawaif poet, Mah Laqa Bai “Chanda” (c. 1767–c. 1824) in the court of late eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Hyderabad. Through her life history, the chapter analyzes the reemployment of “conventional” acts of imperial image making such as composition of poetry, public display of faith, and patronage of architecture and writers by royal women as a means of self-articulation. It will be shown how reading and writing poetry become significant acts of authorship and autobiographical articulation in the specific context of performance, modernity, and mobility in emerging princely cultures.

Introduction

The tawa’ifs have long been compared to the mythological apsaras or devadasis (temple women) in medieval courts as women of the “oldest profession of prostitution and seduction.” Despite the ubiquitous tawa’if of Bombay cinema, writing the history of the tawa’if is a necessary exercise to trace their subjectivity and rethink grand narratives of colonial history and traditions in courtly cultures.

The subject of this chapter is Mah Laqa Bai “Chanda” (c. 1767-c. 1824), a wealthy tawa’if in the princely court of late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Hyderabad. An experienced Urdu poetess, Mah Laqa Bai was the first woman to compile an entire volume or diwan of Urdu poetry in 1798 and a powerful courtesan. She earned revenue from her many jagir (gifted) lands and had an extensive library of manuscripts. A patron of poets and performers, Mah Laqa Bai resided in a grand haveli or palace, which was home to a large retinue of servants as well as a salon to upcoming performers, chroniclers, and poets.

Unlike contemporary understanding of the autobiography as a literary genre, the “autobiographical” articulations of tawa’ifs such as Mah Laqa Bai are not in the form of memoirs or diaries. In earlier courtly contexts, historians have shown how royal women such as queens employed imperial means of self-articulation through the use of public pageantry; traveling with large retinues; commissioning artists or painters; building inns, tanks, and mosques; or minting coins in their own image. Through the narration of Mah Laqa Bai’s life history in this chapter, we will explore the means through which tawa’ifs negotiated their position as courtesans or women of culture. Their reemployment of “conventional” acts of imperial image making such as composing poetry, architectural patronage, and commissioning chronicles will be shown as significant acts of authorship and autobiographical articulation in the context of emerging regional courts of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and the decline of Mughal control. While reading Mah Laqa Bai’s life history and that of her family from the time of her grandmother, we will focus on the lives of those generations of women who chose to become tawa’ifs. Their agency, it will be argued, lay in their attempt to transform their identity through deliberate “erasure” of their past history of displacement and the taking on of new names and movement to different courts or cities in search of livelihood.

Pritchett, Frances W. “Umrao Jan Ada.” Fran’s Favorites: Some Special ‘Study Sites’. Accessed 21 February 2021.

Frances Pritchett’s site about Umrao Jan Ada explores the Urdu novel that inspired the famed Umrao Jaan film in depth. It includes a full English translation of the novel side-by-side with the Urdu original, links to glossaries explaining Urdu words in English, links to scholarship about the novel, and a lovely collection of photographs and illustrations of nautch girls.

Courtney, Chandra and David. “The Tawaif, the Anti-Nautch Movement, and the Development of North Indian Classical Music.” Chandrakantha.com. Accessed 18 February 2021.

Over several pages, this useful website explores the tawaif tradition, the evolution of the will and means to combat the tawaif tradition, and the effects this anti-nautch movement on North Indian music and dance.

Dhar, Debotri. The Courtesans of Karim Street. Niyogi Books, 2018.

Summary

An anonymous letter. The promise of a redgold tree. And Dr. Megan Adams sets off on a ten thousand mile journey. From the scenic suburbs of Princeton and poorer neighborhoods in New Jersey, America, onwards to India, to New Delhi’s opulent enclaves and the narrow bazaars of the old city, Megan’s travel plucks her from the politics of American academia to bring her face to face with the lurking shadows of an untold past. On an entirely different journey is Naina, a young Indian woman who must navigate the stony, impenetrable divide between the old and new sides of Delhi every day. Inheritor of an ancient tradition that pre-dated India’s colonized history, she can still hear the music of the sarangi and the tinkling whisper of anklets. The stories of the two women, their cultures, their pasts and postcolonial presents, collide. And a saga unfolds, of love, loss and liberation, of timeless friendships, and of impossible choices.

Summary from author’s website.

Farooqi, Musharraf Ali. Between Dust and Clay. Freehand Books, 2014.

Summary: In an old and ruined city, emptied of most of its inhabitants, Ustad Ramzi, a famous wrestler past his prime, and Gohar Jan, a well-known courtesan whose kotha once attracted the wealthy and the eminent, contemplate the former splendor of their lives and the ruthless currents of time and history that have swept them into oblivion.

Summary from Goodreads.

Abbas, K.A. “Flowers for Her Feet.” An Evening in Lucknow: Selected Stories, edited by Suresh Kohli. Harper Perennial, 2011, pp 10-35.

Summary: ‘Flowers for Her Feet’ is a short story in which the sexual exploitation of a girl is depicted. Chandra, the dancing girl is harassed and exploited by all, especially the economic elite as the rich people think that women are commodities which can be bought or sold for money.

Summary from Sahapedia.

Kipling, Rudyard. “On the City Wall.” Soldiers Three and In Black and White. Penguin, 1993. pp 153-173.

Summary:

Lalun, a beautiful and talented woman, lives and entertains along the city way of Lahore. Visited by many men, one named Wali Dad is especially friendly. Wali Dad has had an English education and feel uncomfortably places between the European and English worlds. As the story continues, the reader gets an introduction to a leader Khem Singh, someone who may disrupt British rule in India. Khem Singh has been imprisoned though, but escapes. A riot breaks out and Lalun helps an old man out of the riot through her window. She asks the narrator to assistance getting him through the city safely, and he agrees, only to later realize it is Khem Singh. He returns the man to captivity and the rebellion ceases.

Summary from Wikipedia.

Qasim, Suraiya. “Where Did She Belong?” Translated by Mohammad Vazeeruddin. Stories About the Partition of India, vol. II. Edited by Alok Bhalla. Indus, 1994, pp 109-117.

Abstract: This short story is about Munni Bai, a tawaif of unknown parentage in Lahore in the days leading up to and directly following the Partition.

Chander, Krishan. “A Prostitute’s Letter: To Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru and Qai-e-Azam Jinnah.” Translated by Haris Qadeer. River of Flesh and Other Stories: The Prostituted Woman in Indian Short Fiction, edited by Ruchira Gupta. Speaking Tiger Publishing, 2016, pp 184-190.

Abstract: This epistolary short story is written from the point of view of an unnamed sex worker and describes the plight of two girls, one Hindu and the other Muslim, both traumatized by the deaths of their families and placed into sex work following the partition of India and Pakistan.

Sharma, Tripurari. “A Tale from the Year 1857: Azizun Nisa.” Translated by Tutun Mukherjee and A.R. Manzar. Staging Resistance: Plays by Women in Translation, edited by Tutun Mukherjee. Oxford University Press, 2005, pp 120-181.

Abstract: This play tells the story of Azizun Nisa, a courtesan who left her profession during the 1857 Sipahi revolt to become a soldier and fight the British.

Manto, Saadat Hasan. “A Girl from Delhi.” Mottled Dawn: Fifty Sketches and Stories of Partition. Translated by Khalid Hasan, Penguin Random House India, 2011, pp 94-100.

Abstract: This short story follows Nasim Ahktar, a Muslim Nautch girl in Delhi, and her move to Pakistan after the partition of India.

Kamath, Harshita Mruthinti. “Kṣētrayya: The Making of a Telugu Poet.” The Indian Economic & Social History Review, vol. 56, no. 3, July 2019, pp. 253–282, doi:10.1177/0019464619852264.

Abstract

Kṣētrayya is the attributed author of Telugu padams (short lyrical poems) dedicated to Muvva Gōpāla, a form of the Hindu deity Kṛṣṇa. Kṣētrayya is commonly described as a peripatetic poet from the village of Muvva in Telugu-speaking South India who wandered south to the Nāyaka courts of Tanjavur in the seventeenth century. Contrary to popular and scholarly assumptions about this poet, this article argues that Kṣētrayya was not a historical figure, but rather, a literary persona constructed into a Telugu bhakti poet-saint through the course of three centuries of literary reform. A close reading of selected padams attributed to Kṣētrayya reveals the uniquely tangible world of female sexuality painted by the speakers of these poems. However, these padams became sanitized through the course of colonial and post-colonial anti-nautch and Telugu literary reform. In line with this transformation, the hagiography of the poet Kṣētrayya was carefully molded to fit a prefabricated typology of a Telugu bhakti poet-saint. Countering the longstanding narrative of solo male authorship, the article raises the possibility that these padams were composed by multiple authors, including vēśyas (courtesans).

Neti, Leila. “Imperial Inheritances: Lapses, Loves and Laws in the Colonial Machine.” Interventions: International Journal of Postcolonial Studies, vol. 16, no. 2, 1 Aug 2013. pp. 197-214. doi.org/10.1080/1369801X.2013.798914.

Abstract

This essay examines eighteenth- and nineteenth-century inheritance laws in India in order to analyse the intersections between state power, heteronormative reproductivity and colonial structures of race. In particular, I focus on the case of Troup et al. v. East India Company, which involves the estate of Begum Sumroo, one of the wealthiest women in colonial India. I explore the ways in which the normativization of western notions of inheritance, allied with reproductive heterosexuality, worked to undergird the racialized expansion of Empire. I argue that, by law, inheritance and gain came to be reinforced as heteronormative (in its definition, procreative) and patriarchal virtues under colonial rule. Begum Sumroo’s place within this legal scheme poses serious challenges to the logic of colonial inheritance. I use the Begum’s case to expose the mechanisms through which, in order for colonial rule to take effect, sexual normativity was heightened to secure the goals of territorial expansion, thus yoking the notion of private property to various controls over bodily and sexual privacy. I read the Sumroo case as an instance of counter-colonial juridical claims to inheritance and possession that in their violent suppressions reveal the brutality of British power and the illogic – racial and sexual – of early colonial governance.

Sharma, Jyoti P. “Kothi Begam Samru: a tale of transformation in 19th-century Delhi.” Marg, A Magazine of the Arts, 1 June 2010. Rpt. in The Free Library. Accessed 15 Jan 2021.

This article is available free online through The Free Library.

Abstract

“This account by an East India Company officer tells of Begam Samru, an affluent and politically astute lady of rather ambiguous origins who lived in the 19th century. The account makes it amply clear that the Begam had cordial relations with the British who controlled Delhi and its outlying territories from 1803. Indeed, Lord Lake, the architect of the British victory over Delhi, was a frequent guest to the lavish entertainment soirees held at her residence there which were known for their splendid European style banquets, nautch sessions, and fireworks displays.”

Kidwai, Saleem. “The Singing Ladies Find a Voice.” India Seminar, 2004, http://www.india-seminar.com/2004/540/540%20saleem%20kidwai.htm. Accessed 9 September 2019.

This article traces the gradual shift in connotation for the words ganewali and tawaif through the path of ganewalis and tawaifs both historical and fictional. However briefly, it touches upon courtesans such as Umrao Jaan and Begam Samru, as well as the activism of tawaifs. Readers may notice that it is limited in its references/citations.

Chakravorty, Pallabi. Bells of Change: Kathak Dance, Women and Modernity in India. Seagull Books, 2008.

Publisher’s Description:

This is the first critical study of Kathak dance. The book traces two centuries of Kathak, from the colonial nautch dance to classical Kathak under nationalism and post-colonialism to transnationalism and globalization. Reorienting dance to focus on the lived experiences of dancers from a wide cross-section of society, the book narrates the history of Kathak from baijis and tawaifs to the global stage.

Natarajan, Nalini. The Unsafe Sex: The Female Binary and Public Violence against Women. Oxford University Press, New Delhi, 2016

“Chapter 2 analyses the effects of militarisation on public spaces by invoking the wife/tawaif duality within the pretext of the Great Indian Revolt of 1857. According to Natarajan, as the Revolt subsumed men into the army, giving them avenues of stable income, it consequentially led to a devaluation of women at home. Contrarily, the courtesan (tawaif), who by and large fled exploitative homes, could be seen as empowered females with steady income from the military. Yet the binary of the purdahnasheen (veiled) wife versus camp courtesan still rendered public spaces unsafe for women, as sexual purity of all women was at risk with men away at war. This, however, led to another division: the elite educated women facing ‘nationalist seclusion’ (p. 48) were shrouded from Western influences and protected from the public, while the lower-class ‘available’ women, with no rights, became exposed to colonial reforms. Thus, although public spaces manifested contrary movements of empowerment for women who occupied it, they were replete with exploitative characters for women through the ‘separate sphere’ ideology of the street (baazari aurat) and home (grihalakshmi), which strongly impresses the notion that public spaces are unsafe for women.”

(Chakraborty, Sanchayita Paul, and Priyanka Chatterjee. “Book Review: The Unsafe Sex: The Female Binary and Public Violence against Women.” Feminist Review, vol. 119, no. 1, July 2018, pp. 165–167)

Chatterjee, Gayatri. “The Veshyā, the Ganika and the Tawaif: Representations of Prostitutes and Courtesans in Indian Language, Literature and Cinema.” Prostitution and Beyond: An Analysis of Sex Work in India. Eds. Rohini Sahni, V. K. Shankar and Hemant Apte. New Delhi: SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd, 2008. 279-300. SAGE Knowledge

From the introduction:

“The circumstances of the contemporary prostitute might be distinct from those in the past; but literary and cinematic representations continue to be steeped in traditional perception, verbalization and visualization, all well established and sanctioned by the society. Today, she might be a citizen of the Indian state, part of the democracy, with the right to vote and liable to be judged in a civil court; but this makes little difference to her social status. Additionally, the representation-narration around the prostitute continues to tell old tales, seldom revealing the tremendously varied and complex histories behind women now held under one blanket term prostitute.

First and foremost, the paper bases itself upon the premise that there is no one group of women involved here. Going further, it seeks to highlight the fact that behind the formation and existence of these groups of women lies vast and varied social, economic, cultural and political circumstances. And the retrieval of those lost histories (even if partial or incomplete) requires an investigation into terms coined to mark ‘such women’ and the history of their linguistic coinage. Interestingly, the retrieval of this history also requires rigourous survey into the history of literary representation. There has been a long tradition of seeing language and representation as tools for the perpetuation of social inequalities. Though that is true, we now also realize that the production of material history is closely linked with the production of language, literature and arts—that the investigation of one leads to the other. The histories of linguistic coinage and the changing course of words and their meanings are important to know what practices are in currency at what time. What the paper ultimately establishes is that the history of the ‘prostitute’ forms an important chapter in the history of work and woman.

The study shows that to begin with, all these women forming various groups were indicated by different word-coinage. They were professional women or were often treated as such. The more they lost their right to work, the more they had to resort to ‘prostitution’. They are patita or fallen women—what they have fallen from is actually their professional status. Early facts and realities are all obliterated now, replaced by a ghettoization of ‘all such women’ into being only sex workers and the rise of social and moral discourse around them.

Three words veshyā, ganika and tawaif are chosen in this article, which begins with an inquiry into the etymologies behind each term, followed by a survey of representation-narration of the women belonging to these groups—today all seen as ‘prostitute’. Coming from Sanskrit, the word veshyā stands for a prostitute in most Indian languages (there surely are other local terms; this is mostly used for formal or literary purposes). The other two words ganika and tawaif are not in use any more, as that particular social situations in which they existed are no more. Nevertheless, they remain important because of their continuous representation in films of all regions and languages.

It is through the continuous use of language and reproduction of representation that societies maintain their status quo, which in this case is an aggregate of opinions and facts: there is one kind of women who sell sexual favours; they live—this they must—outside the purview of the society; they are morally inferior to all members of the mainstream society—which is the reason why they are ‘outside’. Though they are of one kind, they do not actually make up any caste, class or community—they are women who might or might not stay together (mostly they do). They might have some of their own rules of cluster formation. More commonly, these women belong to a house ruled by a matriarchal figure and so are socially and economically governed by each house-rule; in all other ways they are outside the patriarchal society. The only transaction they have with the mainstream society is when men visit them (for a short span of time) for sexual purposes; the women of the mainstream society have nothing to do with them.”

Kugle, Scott. When Sun Meets Moon: Gender, Eros, and Ecstasy in Urdu Poetry. University of North Carolina Press, 2016.

From JSTOR:

“The two Muslim poets featured in Scott Kugle’s comparative study lived separate lives during the eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries in the Deccan region of southern India. Here, they meet in the realm of literary imagination, illuminating the complexity of gender, sexuality, and religious practice in South Asian Islamic culture. Shah Siraj Awrangabadi (1715-1763), known as “Sun,” was a Sunni who, after a youthful homosexual love affair, gave up sexual relationships to follow a path of personal holiness. Mah Laqa Bai Chanda (1768-1820), known as “Moon,” was a Shi’i and courtesan dancer who transferred her seduction of men to the pursuit of mystical love. Both were poets in the Urdu language of the ghazal, or love lyric, often fusing a spiritual quest with erotic imagery.Kugle argues that Sun and Moon expressed through their poetry exceptions to the general rules of heteronormativity and gender inequality common in their patriarchal societies. Their art provides a lens for a more subtle understanding of both the reach and the limitations of gender roles in Islamic and South Asian culture and underscores how the arts of poetry, music, and dance are integral to Islamic religious life. Integrated throughout are Kugle’s translations of Urdu and Persian poetry previously unavailable in English.”

Kugle, Scott. “Mah Laqa Bai: The Remains of a Courtesan’s Dance.” Dance Matters Too: Markets, Memories, Identities, edited by Pallabi Chakravorty and Nilanjana Gupta, Routledge India, 2018, pp.15-35

From the abstract:

“Mah Laqa Bai is one of Hyderabad’s most famous women. She was a poetess, singer and dancer, and political advisor during her time. She lived from 1768 until 1824 and was active during the era of the Second and Third Nizams (as rulers from the Asaf Jahi dynasty of Hyderabad state were known), and was one of the first women to author a full collection of Urdu ghazals (love poems).1 This chapter takes up the subject of Mah Laqa Bai and was originally written as a keynote address for the conference Dance Matters II. One of the questions this conference asked was, what remains of a dance when the performance is done? What are the traces of dance in the senses, memory, tradition or material objects?”

Sachdeva, Shweta. In Search of the Tawa’if in History: Courtesans, Nautch Girls and Celebrity Entertainers in India (1720s-1920s). 2008. University of London, PhD Thesis.

From the abstract:

Most scholars see the tawa’if either as an unchanging group of hereditary performers or as women engaged in the ‘oldest profession’ of prostitution. This thesis attempts to rethink these linear and separate histories of performers and prostitutes into a dynamic historical model across the long duree of the 1720s to the 1920s. Using multiple language sources I first show that a diverse group of slave girls, prostitutes and women performers made up the varied group of the tawa’if. To trace the continuities and difference in their lives across changing historical contexts of courtly culture and colonial cities, I use Stephen Greenblatt’s theoretical concept of self-fashioning and see these women as agents of their own identity-making. Delving into hierarchies of prostitution and performance, I argue that the most talented and astute amongst the tawa’if became courtesans and wealthy nautch girls through specific acts of self-representation.

Reading their acts in conjunction with their historical images in literary and visual representations, this history sees the tawa’if as historical actors in worlds of image-making. As subjects of courtly culture or urban leisure, the image of the tawa’if could signify both, courtly tradition and emerging modernities of city-life. Rethinking a straightforward history of the ‘decline’ of the ‘courtesan tradition’ since the late nineteenth century, I show that if some tawa’if were marginalised as prostitutes by colonial and reformist praxis, others became celebrity entertainers. Through their use of new technologies of print, photography and recording, and strategic political acts such as forming local caste associations, the tawa’if in this history will emerge to be acute observers and participants in the milieux of courtly cultures and emergent nation-space.

Singh, Vijay Prakash. “From Tawaif to Nautch Girl: The Transition of the Lucknow Courtesan.” South Asian Review, Vol. 35, No. 2, 2014.

Abstract

Lucknow with its Nawabi court and its patronage of dance and music has been for over two centuries a center of the art of fine language and etiquette. This paper focuses primarily on the dancing women, tawaif, who performed outside the court in private salons or kothas. As highly accomplished women catering to the nobility, the tawaif enjoyed a high degree of financial independence and social prestige. After the establishment of the East India Company, the tawaif were solicited as entertainers for British social gatherings and later pushed into prostitution. The paper shows the decline of the tawaif as representatives of culture to mere social entertainers and subsequently as bazaar prostitutes surviving on the margins of society.

Caldwell, John. “The Movie Mujra: The Trope of the Courtesan in Urdu-Hindi Film.” Southeast Review of Asian Studies, Vol. 32, 2010, p. 120+.

Abstract

The trope of the courtesan is found in many Urdu-Hindi films from the earliest period of Indian cinema. The courtesan was essential to the film musical because her character could dance and sing when the more modest heroine could not. The courtesan could also express sexual desire, longing for freedom and independence, and choice in the matter of lovers. She expressed herself primarily through the medium of the mujra-ghazal, a musical set-piece derived from nineteenth-century century courtesan culture in northern India. This article traces the musical and dramatic trajectory of the trope of the courtesan with reference to two of the most famous courtesan films: Pakeezah (1972) and Umrao Jaan (1981).

Tawaif. Directed by Baldev Raj Chopra, performances by Rishi Kapoor and Rashi Agnihotri, Sunrise Films, 1985.

Summary

After a crime lord leaves a courtesan, Sultana, in the home of the unsuspecting Dawood and threatens to kill him if anything happens to her, Dawood must pretend she is his new bride. Dawood, who is forming a romance with a local author writing a book about a courtesan, must carefully conceal Sultana’s identity while avoiding unsavoury circumstances. Despite Dawood’s resistance, a romance develops, and the two must ensure Sultana’s escape from the crime lord and ensure a happy ending.

Questions to Consider

- A common theme of the Bollywood courtesan genre is courtesans wishing to escape their lives into “respectable” heterosexual marriages (see Poonam and Hubel to learn more.) This is certainly true of Tawaif’s ending, but is Sultana’s courtesan life not considered “respectable”? Does the film respect Sultana herself? Does it respect her work? Can they be separated?

- Dawood is very interested in Poonam’s book about courtesans, but looks down upon the real courtesan, Sultana. Who else consumes media representations about courtesans while disrespecting the people upon which those representations are based? What might the film be suggesting here about representation and consumption?

- Was Sultana respectable before she was married? If so, how does the marriage serve to influence opinions of Sultana—those of the audience and the other characters?

- Several scenes suggest that Sultana believes her work is shameful. For example, while staying with Dawood, Sultana refuses to sleep on the wedding bed the landlady had intended for her son, believing that as a courtesan, she is “unworthy” of lying on such a bed, or even of marriage in general. From where do we believe Sultana absorbed this opinion? Is this opinion of courtesans shared by the other characters? Is it shared by the film?

- Does Sultana have a say in the work she does? In the world of this film, do other courtesans? Would Sultana’s happy ending be accessible to a courtesan who liked or chose her work? Does this film appear to believe that courtesans can like their or choose their work?

- In what ways could viewing courtesans as innocent victims of circumstance (e.g: trafficking, poverty) help them? In what ways could that view pose a risk?

Jagpal, Charn Kamal Kaur. “I Mean to Win”: The Nautch Girl and Imperial Feminism at the Fin de Siècle. 2011. University of Alberta, PhD Dissertation.

This dissertation is available to read for free online at the University of Alberta’s ERA website.

Abstract

Grounded in the methodologies of New Historicism, New Criticism, Subaltern Studies, and Colonial Discourse Analysis, this dissertation explores English women‘s fictions of the nautch girl (or Indian dancing girl) at the turn of the century. Writing between 1880 to 1920, and within the context of the women‘s movement, a cluster of British female writers—such as Flora Annie Steel, Bithia Mary Croker, Alice Perrin, Fanny Emily Penny and Ida Alexa Ross Wylie—communicate both a fear of and an attraction towards two interconnected, long-enduring communities of Indian female performers: the tawaifs (Muslim courtesans of Northern India) and the devadasis (Hindu temple dancers of Southern India). More specifically, the authors grapple with the recognition that these anomalous Indian women have liberties (political, financial, social, and sexual) that British women do not. This recognition significantly undermines the imperial feminist rhetoric circulating at the time that positioned British women as the most emancipated females in the world and as the natural leaders of the international women‘s movement. The body chapters explore the various ways in which these fictional devadasis or tawaifs test imperial feminism, starting with their threat to the Memsahib‘s imperial role in the Anglo-Indian home in the first chapter, their seduction of burdened Anglo-Indian domestic women in the second chapter, their terrorization of the British female adventuress in the third chapter, and ending with their appeal to fin-de-siècle dancers searching for a modern femininity in the final chapter. My project is urgent at a time when imperial feminism is becoming the dominant narrative by which we are being trained to read encounters between British and Indian women, at the expense of uncovering alternative readings. I conclude the dissertation by suggesting that the recovery of these alternative readings can be the starting point for rethinking the hierarchies and the boundaries separating First World from Third World feminisms today.

Maciszewski, Amelia. “Texts, Tunes, and Talking Heads: Discourses about Socially Marginal North Indian Musicians.” Twentieth-Century Music, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 121-144.

In this study, criss-crossing discourses – written, visual, and aural – are brought together in an effort to shed light on a section of the tawa’if (traditional courtesan) community in contemporary North India. As a kind of companion text to my point-of-view documentaries Guria, Gossip, and Globalization and Chandni’s Choice, I present an overview of the NGO Guria. This organization works to empower tawa’ifs to reclaim their liminality as artists, able to move back and forth between their own profoundly socially marginalized community and mainstream society, a privilege they enjoyed historically but have virtually lost in the present day. I have juxtaposed this with an exegesis of talk, including gossip, about and by these performers and their music. This includes issues of their gossip- and media-driven legacy that have led to their current position, often dangerously vulnerable, in the global marketplace. Finally, I examine the life of a teenage member of a musical matriarchy whose foremothers have been somewhat successful at continuing to traverse the borderlands between various levels of society.

Boejharat, Jolanda Djaimala. “Indian Courtesans: From Reality to the Silver Screen and Back Again.” IIAS Newsletter, Vol. 40, No. 8, 2006.

This article is available for free online through the Leiden University Repository: https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/handle/1887/12710

From the Introduction – Modern Courtesans

People today speak nostalgically about the golden age of courtesans, when their company was much appreciated and an accepted part of aristocratic life. Nevertheless, the current practice of this seductive art as found in today’s brothels (kotha) is despised, while its practitioners are considered outcasts operating on the margins of society. Of course there is great variety in India’s red-light districts: from child prostitutes to call girls in modern city bars and women who still use the mujarewali tradition of dancing and singing as part of their seductive technique. Their daily lives and their nighttime practices place them in a twilight zone, serving a male clientele without regard to caste or religion.

Some artists and researchers say that traditional mujarewali no longer exist, as the artistic expressions of today’s courtesans are in no way comparable to those of bygone days. Still, although their techniques have changed, these women perform the arts of seduction, and their customers visit them not only for their public services, but to return to an earlier time, to leave behind the cares of today and of the future.

From the Introduction – Courtesan Films

The Bollywood film industry, with 900 releases annually, is among the largest in the world. Many film producers’ works feature both historical courtesans and their present-day representatives…. The introduction of sound in the 1930s gave birth to a tradition of films featuring embedded music and dance

sequences. Of these, the courtesan genre includes such well-known examples as DevDas (1955) Pakeeza (1971) and Umrao Jan (1981). Early courtesan films idealized the beauty and artistic skills of the historical mujarewali and portrayed prostitutes restored to social respectability through marriage. The narratives were interspersed with song and dance sequences similar to what we assume to have been traditional mujara practice.

Ward, Leda. Images of a Decolonizing India: Bollywood’s Tawai’f and the Postcolonial Muslim. Thesis, Barnard College, Dance Department, Columbia University, 2008.

This thesis is available for free online through Barnard College’s Dance Department.

Ward’s thesis explores the ways in which the tawa’if figure in 4 major Bollywood films—the nameless tawai’f of Sahib Bibi aur Ghulam, Chitralekha of Devdas, Umrao Jaan of Umrao Jaan, and Sahib Jaan of Pakeezah—”retell the story of Muslims in colonial and postcolonial India,” particularly in terms of displacement and marginalization. Ward contextualizes her analyses using the historical background of pre-colonial tawa’ifs and of partition.

Ram, Anjali. “Framing the Deminine: Diasporic Readings of Gender in Popular Indian Cinema.” Women’s Studies in Communication, vol.25, no.2, 2002, pp.25-52.

Abstract

This essay focuses on the ways in which Indian immigrant women actively engage and interpret Indian cinema. Employing an ethnographic approach, the analysis moves between readers’ readings and film texts in order to locate how Indian cinema mediates the constitution of gendered identities in the diaspora. Keeping alive the sense of agency, this study demonstrates that Indian women viewers/readers simultaneously comply with and resist the dominant patriarchal representations that saturate Indian cinema.

Notable Excerpt (pp. 44-45)

The image that most directly counters the purity/sanctity model of Indian womanhood in cinema is that of the courtesan. Chakravarty (1993) comments that the courtesan, as historical character and cinematic spectacle, is one of the most enigmatic figures to haunt the margins of Indian cultural consciousness. Socially decentered, she is yet the object of respect and admiration because of her artistic training and musical accomplishments. The courtesan is an ambiguous/romantic figure in multiple senses. She embodies both Hindu and Muslim social graces and represents what Chakravarty calls “female power-cum-vulnerability”. Rekha’s most memorable roles have involved playing the courtesan directly or indirectly. In Silsila she plays the role of the “other woman,” which is echoed in variations in Basera (1985). In Mukadaar ka Sikandar she plays a bazaar entertainer in love with the tortured hero played by Bachchan, again blurring the boundaries between real/reel life, fiction/fantasy as film gossip and text intersect. In Utsaav, she plays Vasantsena, the legendary courtesan of ancient India, whose life is narrated in the classical Sanskrit play of the fourth century A.D. entitled Mirchchakatika (The Little Clay Cart). However, it is in Umrao Jaan (198 1), which Chakaravarty (1993) calls the quintessential courtesan film of Indian cinema, where she plays both desiring subject and desired object and reveals the contested nature of the feminine in the collective Indian imaginary.

Anderson, Michael. “Body and Soul: Pakeezah and the Parameters of Indian Classical Cinema.” Tativille, 16 May 2012.

This article is available for free online through Tativille: http://tativille.blogspot.com/2012/05/body-and-soul-pakeezah-and-parameters.html

From the Introduction

The classical Indian cinema today is no more in need of justification than was its Hollywood counterpart in the late 1960s. This is not to argue that either cinema has been immune historically to dispersions against its artistic character, nor even that it no longer is; as commercial industries, each has and continues to arouse criticism for its relationship to the marketplace, and for its supposed concessions to capitalist enterprise. Still, to say the neither requires justification is to make the least controversial of claims: that art and entertainment can and do coexist in the finest instances of each tradition….

….Writer-director Kamal Amrohi’s Pakeezah (‘Pure Heart,’ 1972) succeeds in “validating” the concept of a classical Indian cinema: that is, Pakeezah’s existence – and indeed its elevated artistic status – is altogether implausible outside the contours of Bollywood filmmaking. This is not to suggest merely that Amrohi’s film required the commercial and/or technological institutions of the Bollywood industry. Rather, Pakeezah owes its existence to the singular formal structure of the popular Indian cinema. Specifically, Amrohi’s picture is constructed according to Bollywood filmmaking’s defining epic structure; its characteristic recourse to diegetic musical sequences – with motivations that are not always readily discernable; and its wild disjunctures of space and time. This is to say that Pakeezah adheres to a set of conventions that mark its distance from the characteristic economy of Hollywood studio filmmaking, even as it instantiates a popular idiom of its own.

At the same time, Pakeezah does not represent simply an adoption of this popular form, but instead an appropriation of its formal singularities for its particular semantic ends. That is, while Pakeezah utilizes a pre-existing mass-art form, its application is calibrated to match the idiosyncrasy of the film’s content. Thus, though Amrohi has not invented a cinematic idiom unique to his film, he has nonetheless succeeded in producing the same level of organic rigor – between form and discourse – than have those artists who have remade the language of their cinema in the image of their subjects: from Carl Theodor Dreyer to Chantal Akerman to Abbas Kiarostami, among scores of others. It is almost as if we might say that the language of the classical Indian cinema is Amrohi’s, to the degree that it was under his direction in Pakeezah that the form appeared to become as malleable as it long has been for the greatest exemplars of counter-cinema, who have all transformed the language of their art to match the content of individual works. Pakeezah thusjustifies the classical Indian cinema as it not only marks it as but in fact makes it a singularly expressive form.

Courtesans of Bombay. Dir. Ismail Merchant. Perf. Saeed Jaffrey, Zohra Segal. Merchant Ivory Productions. 1983. DVD.

This 1983 docudrama examines an enclosed area of Mumbai known as Pavan Pool, a low-income apartment community home to many courtesans. The film explores their daily lives and showcases their performances. Notably, much of the work is scripted: its three interview subjects (a landlord, a retired courtesan and a frequent patron) are all played by actors whose lines were written by screenwriter Ruth Prawer Jhabvala. The landlord speaks about the working conditions at the compound, the retired courtesan speaks about how the tawaif practice has changed over time, and the patron speaks about his relationship with and perception of courtesans and their art. The scripted interviews are presented alongside footage of the real residents and performers of Pavan Pool, but videos of the real residents speaking amongst each other are not subtitled.

While the footage of tawaifs’ performance may be useful and interesting to our readers, the dramatization of the documentary draws some interesting ethical questions.

We highly recommend reading Geeta Thatra’s “Contentious Socio-Spatial Relations: Tawaifs and Congress House in Contemporary Bombay/Mumbai” alongside viewing this documentary.

Questions to Ask About Courtesans of Bombay and Other Documentaries

- This documentary was commissioned by BBC Channel 4. It was made by British people for British consumption. How might this funding and purpose affect the documentary’s content?

- Given that this film’s subtitled speech—the speech understandable to an English-speaking British audience—is entirely scripted, can this film be accurately called a documentary? Is it drama? Is it both?

- To what degree do the Pavan Pool courtesans appear to be involved in constructing the film’s narrative? Whose insights are included and whose are left out?

- What real-life political impacts can documentaries have on the groups they feature? What ethical problems should documentary filmmakers consider when telling stories about marginalized groups? Could the Pavan Pool courtesans benefit from this film? Could the film cause them harm?

- The landlord consistently presents the Pavan Pool courtesans as naïvely causing their own financial ruin: according to him, they keep hoping for an improbable film contract, they fight each other over cheating men, and some cling to outdated and unprofitable traditions. What does this representation suggest about the courtesans? Are viewers encouraged to believe the landlord is well-informed and truthful? What other reasons might exist for why the courtesans are struggling? How could this representation impact the audience’s view of these courtesans’ agency?

Leonard, Karen. “Political Players: Courtesans of Hyderabad.” The Indian Economic and Social History Review, vol. 50, no. 4 (2013), pp. 423-48

From the abstract: “Important recent works on the Mughal state and women in the Indo-Muslim world have not considered courtesans or tawa’ifs, the singing and dancing women employed by Indo-Muslim

states and nobles, to be significant participants in politics and society. Drawing on detailed

archival data from late nineteenth century Hyderabad state and other historical materials,

I argue that courtesans were often elite women, cultural standard-setters and wielders of political

power. Women whose art and learning gained them properties and alliances with powerful

men, they were political players in precolonial India and in the princely states. They successfully

negotiated administrative reforms in princely states like Hyderabad, continuing to secure protection

and patronage while in British India they began to be classified as prostitutes. Colonial

and modern India have been less than kind to courtesans and their artistic traditions, and more

research needs to be done on the history of courtesans and their communities.”

Gupta, Trisha. “Bring on the Dancing Girls.” Tehelka, no 6, vol 44. November 7, 2009.

Gupta’s article, largely drawing from Saba Dewan’s documentary The Other Song, examines the prominence of the courtesan figure in popular culture and briefly outlines the shifting attitudes towards tawaif music and dance through the 19th and early 20th century. Gupta notes how social attitudes forced some artists to reinvent themselves and distance themselves from their pasts, as well as how certain songs had words and lyrics rewritten to be less suggestive and more ‘respectable.’

Kesavan, Mukul. “Urdu, Awadh, and the Tawaif: the Islamicate roots of Hindi Cinema.” Forging Identities: Gender, Communities and the State in India. Edited by Zoya Hasan, Westview, 1994, pp. 244-257.

Kesavan’s essay explores the relationship between Hindi cinema and what Kesavan calls “Islamicate” culture, referring “not directly to the religion, Islam, itself but to the social and cultural complex historically associated with Islam and Muslims.” Kesavan notes three key links between Islamicate culture and cinema, notably Urdu, Awadh (the setting of, among many texts, Umrao Jaan) and the cinematic figure of the tawaif.

Vanita, Ruth. Dancing With the Nation: Courtesans in Bombay Cinema. Speaking Tiger, 2017.

Ruth Vanita’s Dancing with the Nation: Courtesans of Bombay Cinema is an important piece of scholarship detailing the representation of tawaifs in Hindi cinema and how these representations shape and were shaped by the culture in which they were produced. Throughout the course of writing this book, Vanita closely studied over 200 films; we encourage encourage our readers to purchase a copy of this valuable book for themselves or their libraries.

A substantial excerpt from this book can be found on The Daily O.

Publisher’s Summary

This summary was obtained from the Speaking Tiger website.

“Acknowledging courtesans or tawaifs as central to popular Hindi cinema, Dancing with the Nation is the first book to show how the figure of the courtesan shapes the Indian erotic, political and religious imagination. Historically, courtesans existed outside the conventional patriarchal family and carved a special place for themselves with their independent spirit, witty conversations and transmission of classical music and dance. Later, they entered the nascent world of Bombay cinema—as playback singers and actors, and as directors and producers.

In Ruth Vanita’s study of over 200 films from the 1930s to the present—among them, Devdas (1935), Mehndi (1958), Teesri Kasam (1966), Pakeezah (1971), Ram Teri Ganga Maili (1985), Ahista Ahista (1981), Sangeet (1992) and Ishaqzaade (2012)—courtesan characters emerge as the first group of single, working women depicted in South Asian movies. Almost every female actor—from Waheeda Rehman to Rekha and Madhuri Dixit—has played the role, and compared to other central female roles, these characters have greater social and financial autonomy. They travel by themselves, choose the men they want to have relations with and form networks with chosen kin. And challenging received wisdom, in Vanita’s analysis of films such as The Burning Train (1980) and Mujhe Jeene Do (1963), courtesan characters emerge as representatives of India’s hybrid Hindu-Muslim culture rather than of Islamicate culture.

A rigorously researched and groundbreaking account of one of the less-examined figures in the study of cinema, Dancing with the Nation is also a riveting study of gender, sexuality, the performing arts and popular culture in modern India.”

Kohli, Namita. “In the company of the tawaif: Recreating the magic with darbari kathak.” Hindustan Times, 27 Aug 2016.

This piece profiles Kathak performer Manjari Chaturvedi and her project to recreate kathak dances once performed by courtesans, as part of her show “The Courtesan – An Enigma.” Kohli discusses some of the negative stereotypes surrounding courtesans and their representation in Bollywood and wider media, contrasting them with Chaturvedi’s research and attempts to build a more accurate, nuanced and dignified portrayal of courtesans and their role in art and history. As Chaturvedi herself notes, “I had to do this for her, and for all the other tawaifs who deserve that dignity.”

Hubel, Teresa. “From Tawa’if to Wife? Making Sense of Bollywood’s Courtesan Genre.” The Magic of Bollywood: At Home and Abroad. Ed. Anjali Gera Roy. Sage, 2012, pp. 213-233.

Dr. Teresa Hubel is a co-creator of the Courtesans of India project. As part of her commitment to open scholarship, she offers this and other works for free on her Selectedworks page.

Although constituting what might be described as only a thimbleful of water in the ocean that is Hindi cinema, the courtesan or tawa’if film is a distinctive Indian genre, one that has no real equivalent in the Western film industry. With Indian and diaspora audiences generally, it has also enjoyed a broad popularity, its music and dance sequences being among the most valued in Hindi film, their specificities often lovingly remembered and reconstructed by fans. Were you, for example, to start singing “Dil Cheez Kya Hai” or “Yeh Kya Hua” especially to a group of north Indians over the age of about 30, you would not get far before you would no longer be singing alone.’ Given its wide appeal, the courtesan film can surely be said to have a cultural, psychological, and ideological significance that belies the relative smallness of its genre. Its meaning within mass culture surpasses its presence as a subject. And that meaning, this chapter will argue, is wrapped up not only in the veiled history of the courtesans, a history that Hindi cinema itself has done much to warp and even erase, but in the way in which the courtesan figure camouflages a deep-seated anxiety about female independence from men in its function as a festishized “other” to the dominant female character, the wife or wife-wannabe, whose connotation is so overdetermined in mainstream Indian society that her appearance in Hindi cinema seems mandatory.

Pakeezah. Directed by Amrohi Kamal, Mahal Pictures Pvt. Ltd., 1972.

In this famed courtesan movie, the protagonist Sahibjaan is born to a tawaif, Nargis, who was desperate to escape courtesan life but who was spurned by her lover’s family. Nargis dies in childbirth, and Sahibjaan’s aunt, Nawabjaan, raises Sahibjaan as a tawaif, where she learns to be an excellent and alluring singer and dancer. One night, an unknown poet leaves a poem at Sahibjaan’s feet while she sleeps. She does, eventually, meet him, and, stunned by her beauty and innocence, he renames her “Pakeezah”—meaning “pure”—and proposes to elope with her to take her away from courtesan life. But many painful trials await.

Questions to think about:

- What does Pakeezah’s purity indicate about the film’s “idea” of tawaifs? Can any tawaif be pure, or is Pakeezah exceptional?

- Can a tawaif be “forgiven” from the film’s perspective? Can a tawaif escape?

- What dimensions of sympathy does the film create for Pakeezah? Is the sympathy respectful? Paternalistic?

- Does the film imply tragedy is in store for all courtesans, or just Pakeezah? How culpable are courtesans in their fate?

Devdas. Directed by Sanjay Leela Bansali, Mega Bollywood Pvt., 2002.

In this 2002 film adaptation of the 1917 novel of the same name, the protagonist Devdas is about to return home after 10 years of law school in England. Devdas’s mother, Kaushalya Mukherjee, tells her poor neighbour Sumitra, who is overjoyed. Sumitra’s daughter Paro and Devdas are loving childhood friends. Both families believe Devdas and Paro will get married, but Devdas’s conniving sister-in-law reminds Devdas’s mother, Kaushalya of Paro’s “inappropriate” maternal lineage of nautch girls.

Heartbroken by his family’s rejection of Paro, Devdas leaves his parents’ house and takes refuge at a brothel, where he becomes an alcoholic and where a good-hearted tawaif named Chandramukhi falls in love with him. Eventually he becomes desperate to return to Paro, but a number of tribulations stand in the way of Devdas, Paro, and Chandramukhi’s ideals.

Notable Elements

- Develops a positive sisterhood between Chandramukhi and Paro, rather than following the common film trope of situating women as hostile or antagonistic to one another

- Challenges the Mukherjees’ arrogance about their wealth as well as their double-standards about tawaifs: “Aristocrats’ lust creates the bastards they scorn!” “You [rich people] act high and mighty, but you sell your daughters for bride prices!” “The money you flash around lays at harlots’ feet!”

Questions to consider:

- If the film in some ways tries to challenge anti-nautch attitudes; what is the significance of the fact that the lowest points of Devdas’s life occur in a brothel, or that mostly evil men go to see tawaifs?

- Numerous characters shame women for their supposed sexuality. Overall, does it appear like the film to some degree condones this shaming?

- What dimensions of sympathy do we have for Devdas? What about Paro? How culpable are they in their fates?

Ansari, Usamah. “‘There are Thousands Drunk by the Passion of These Eyes.’ Bollywood’s Tawa’if: Narrating the Nation and ‘The Muslim.’” South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, vol. 31, no. 2, 2008, pp. 290-316.

From the Introduction