Abstract

This chapter addresses the issue of women and self-representation through the life of a wealthy courtesan and tawaif poet, Mah Laqa Bai “Chanda” (c. 1767–c. 1824) in the court of late eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Hyderabad. Through her life history, the chapter analyzes the reemployment of “conventional” acts of imperial image making such as composition of poetry, public display of faith, and patronage of architecture and writers by royal women as a means of self-articulation. It will be shown how reading and writing poetry become significant acts of authorship and autobiographical articulation in the specific context of performance, modernity, and mobility in emerging princely cultures.

Introduction

The tawa’ifs have long been compared to the mythological apsaras or devadasis (temple women) in medieval courts as women of the “oldest profession of prostitution and seduction.” Despite the ubiquitous tawa’if of Bombay cinema, writing the history of the tawa’if is a necessary exercise to trace their subjectivity and rethink grand narratives of colonial history and traditions in courtly cultures.

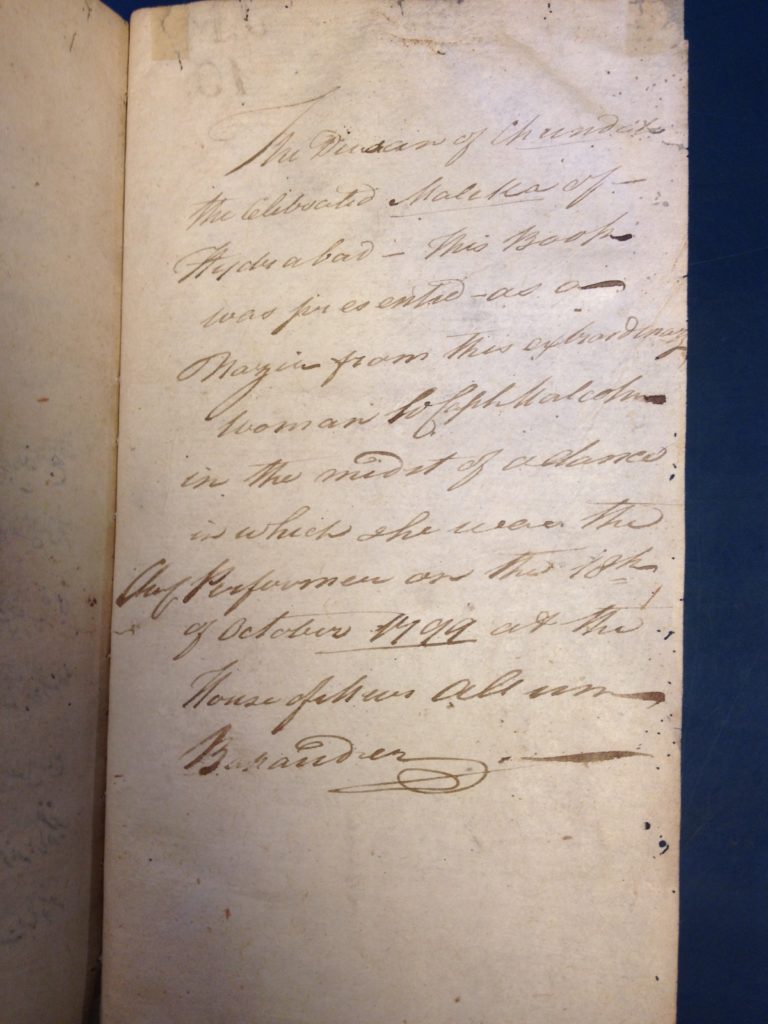

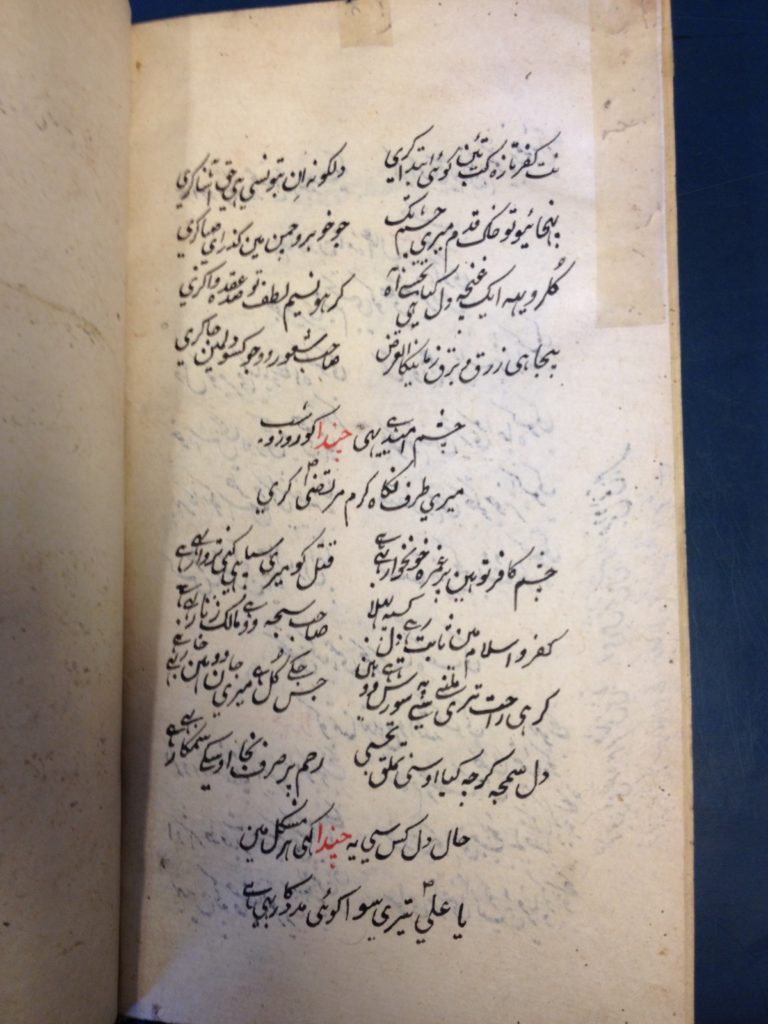

The subject of this chapter is Mah Laqa Bai “Chanda” (c. 1767-c. 1824), a wealthy tawa’if in the princely court of late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Hyderabad. An experienced Urdu poetess, Mah Laqa Bai was the first woman to compile an entire volume or diwan of Urdu poetry in 1798 and a powerful courtesan. She earned revenue from her many jagir (gifted) lands and had an extensive library of manuscripts. A patron of poets and performers, Mah Laqa Bai resided in a grand haveli or palace, which was home to a large retinue of servants as well as a salon to upcoming performers, chroniclers, and poets.

Unlike contemporary understanding of the autobiography as a literary genre, the “autobiographical” articulations of tawa’ifs such as Mah Laqa Bai are not in the form of memoirs or diaries. In earlier courtly contexts, historians have shown how royal women such as queens employed imperial means of self-articulation through the use of public pageantry; traveling with large retinues; commissioning artists or painters; building inns, tanks, and mosques; or minting coins in their own image. Through the narration of Mah Laqa Bai’s life history in this chapter, we will explore the means through which tawa’ifs negotiated their position as courtesans or women of culture. Their reemployment of “conventional” acts of imperial image making such as composing poetry, architectural patronage, and commissioning chronicles will be shown as significant acts of authorship and autobiographical articulation in the context of emerging regional courts of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and the decline of Mughal control. While reading Mah Laqa Bai’s life history and that of her family from the time of her grandmother, we will focus on the lives of those generations of women who chose to become tawa’ifs. Their agency, it will be argued, lay in their attempt to transform their identity through deliberate “erasure” of their past history of displacement and the taking on of new names and movement to different courts or cities in search of livelihood.