Dr. Teresa Hubel is a co-creator of the Courtesans of India project. As part of her commitment to open scholarship, she offers this and other works for free on her Selectedworks page.

On the other side of patriarchal histories are women who are irrecoverably elusive, whose convictions and the examples their lives might have left to us–their everyday resistances as well as their capitulations to authority–are at some fundamental level lost. These are the vast majority of women who never wrote the history books that shape the manner in which we, at any particular historical juncture, are trained to remember; they did not give speeches that were recorded and carefully collected for posterity; their ideals, sayings, beliefs, and approaches to issues were not painstakingly preserved and then quoted century after century. And precisely because they so obviously lived and believed on the underside of various structures of power, probably consistently at odds with those structures, we are eager to hear their voices and their views. The problem is that their individual lives and collective ways of living them are impossible to recover in any form that has not already been altered by our own concerns. In making them speak, by whatever means we might use (archives, testimonials, court records, personal letters, government policy), we are invariably fictionalizing them because we are integrating them into narratives that belong to us, that are about us. Given the inevitability of our using them for our own purposes, we cannot justify taking that all-too-easy (and, as this essay will suggest), middle-class stance that posits us as their champions, their rescuers from history. It falls to us to find other motives for doing work that seeks them.

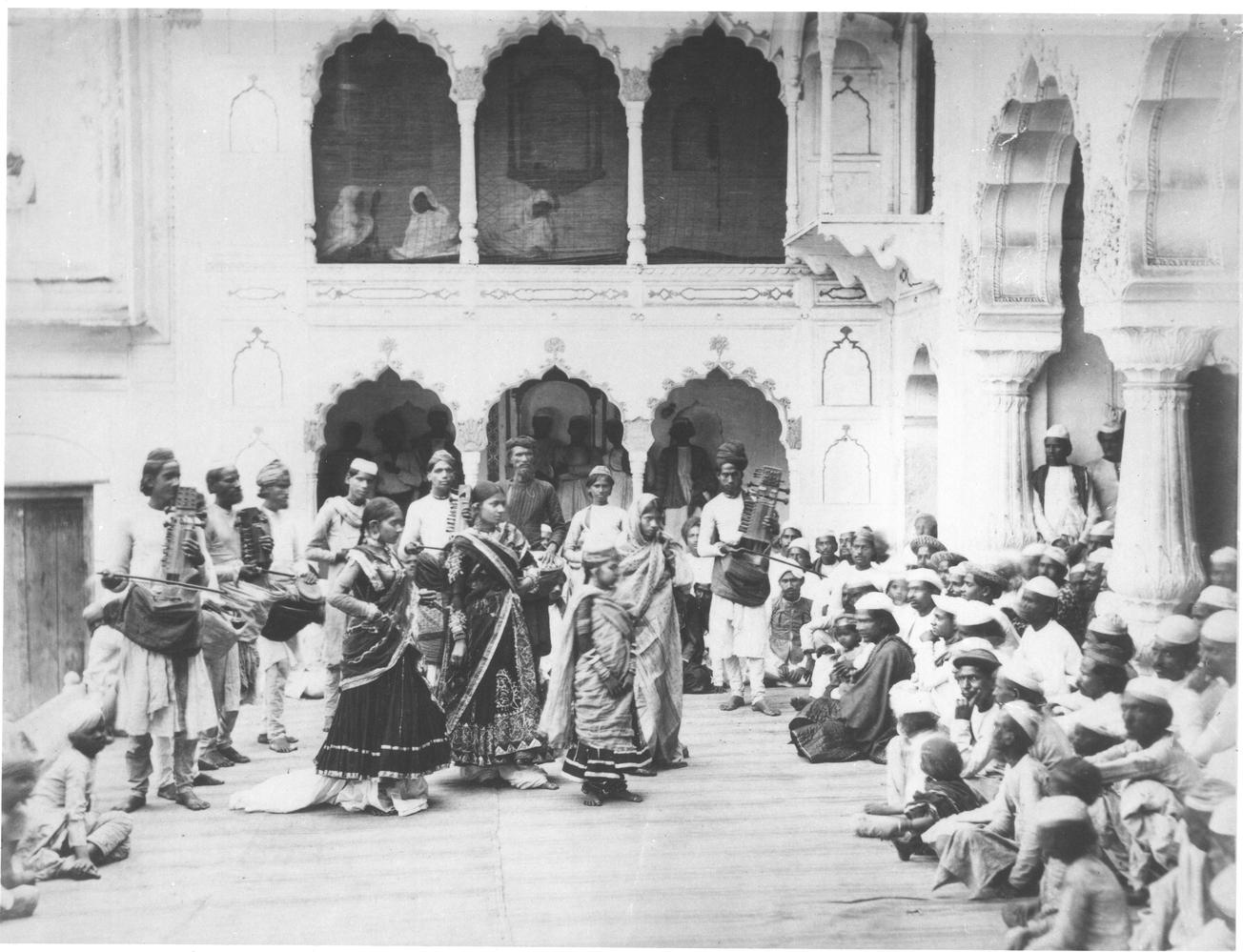

In the case of this essay, the “them” are the devadasis or temple dancers of what is now Tamilnadu in southern India (the term devadasis literally translates as “female servant of God”), especially those dancers who were alive during the six decades of the nationalist movement. This movement was meant to grant Indians freedom from colonial oppression and give them a nationalist identity, but if it succeeded, at least to some extent, in accomplishing these things, it did so at the cost of the devadasis and their dance traditions. Janet O’Shea (1998) explains the logic through which the newer institution, nationalism, drove out the older one, the profession and culture of the devadasis: “Indian nationalism has often required a shift away from cultural diversity in order to construct a unified image of nationhood . . . The de’rlagfns were threatening . . because they represented, for the new nation, an uncomfortable diversity of cultural practices and cultural origins” (p, 55). Most scholars who have written about the modern history of the devadasis would agree with this explanation. To the elite men and women who had the greatest say in what would constitute the new Indian nation, the devadasis were an embarrassing remnant of the pre-colonial and pre-nationalist feudal age and, as such, could not be permitted to cross over into the homogeneity that the nationalists hoped would be post-colonial India.

The campaign to suppress the devadasis and to eliminate their livelihoods culminated in the Madras Devadasis Prevention of Dedication Act of 1947, an act brought about largely through the efforts of middle-class Indian nationalists who were also social reformers and, often, feminists–that is, advocates not only of nationalism but of the burgeoning women’s movement that was to ensure so many of the legal rights Indian women enjoy today.

That feminists who were determined to extend the rights of some women should also work to deny rights to other women is the conundrum that this essay examines.

This chapter was originally published in Intercultural Communications and Creative Practice: Dance, Music and Women’s Cultural Identity.