The Woodstock Industrial Institute Collecting Book: A Case Study of the Black Community in Chatham

Kevin den Dunnen

This blog uses the collecting book from the Woodstock Industrial Institute as a starting point to analyze the segregated history of Chatham’s schools, the difficulties faced by the Black community in a supposed “Promised Land,” and the recent efforts of the community to honour their history despite the loss of significant landmarks.

The collecting book stands as a relic for the fight to end the segregated network of schools in Chatham, Kent County, and the province of Ontario. Kent County segregated schools for much of the nineteenth century. This segregation began without any specific laws requiring such discrimination. Egerton Ryerson, Canada West’s superintendent of education, had left the decision of segregation up to local school boards, [1] who he believed could best respond to racial dynamics in their local communities. In practice, this passive law gave school boards the power to discriminate against Black people with little need for justification aside from claiming the potential for racial conflict.[2] Many people in the Black community did not live near the few schools available to them in the nineteenth century. [3] This made the process of transporting children to school difficult for many families. In addition, those who were able to attend school Chatham most likely did not receive a strong education either. The schools open to the Black students had far too little space and resources for the number of students attending. This overcrowding of the schools meant teachers and assistants could not provide the necessary attention required to educate students properly. [4]

The Black community in Chatham did not meekly accept these conditions. They had long identified such issues with the education system and passionately argued for the official desegregation of schools. In 1893 and after many years of trying, the long campaign to desegregate Chatham succeeded when the Kent County Civil Rights League put forth a variety of plans to force the board to open all schools for Black children. [5] This was not the end of racial struggles in Chatham. The necessity of building the Woodstock Industrial Institute demonstrates the continuing lack of educational resources for the Black community. However, the desegregation of schools was a major victory for the Kent County Civil Rights League and shows the perseverance of the Black community to better their position in a resistant society.

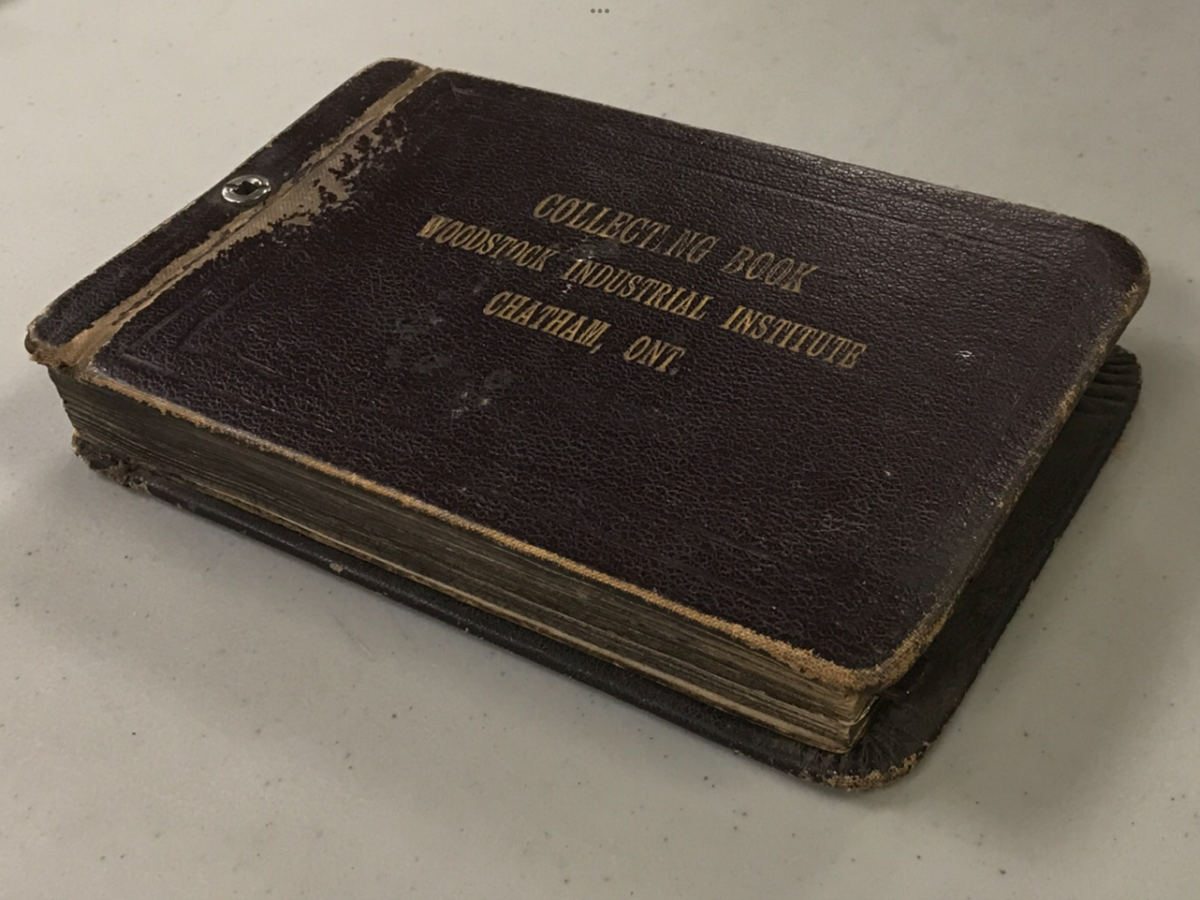

This collecting book holds the memory of the Woodstock Industrial Institute. The Woodstock Industrial Institute opened in 1908 to address the lacking industrial educational opportunities in the east side of Chatham where many members of the Black community lived (Figure 1). Figure 2 shows the location of the school on King Street Chatham. Within this neighbourhood were several other institutions of importance to the Black community such as the “Baptist Church (Colored)” and “Campbell Chapel (Colored).” The 1913 Insurance Plan informed insurance companies of the makeup for each building such as brick, wooden, or stone exterior so they could tailor insurance plans and prices accordingly. For historians, such maps supply a highly detailed map of buildings in the area and the building materials. Using this map from one small area in Chatham, we can imagine the area as a hub for the Black community with such significant buildings like the churches found nearby. By 1921, the school employed twenty-seven teachers in departments such as wireless telegraphy, blacksmithing, music, sewing and dressmaking, and electroplating. All these departments addressed workforce needs withing the community. [6] The school closed in 1927 to become a community centre and offer fun activities like community dances, craft and arts sessions, and hosting site for various clubs like the Quarter Century Club. [7] In 1984, the city took down the building after community plans to restore the building failed. [8]

Figure 2. Chas. E. Goad CO., 1913 Insurance Plan of Chatham, Ontario, photograph (London, n.d.), Western University Archives and Research Collection, A fire insurance plan map of Chatham in 1913. The map shows the makeup of each building for insurance companies to easily know what plans the building would fall under. For example, a building made of wood would require different insurance costs than brick.

The front cover of the collecting book contains a written statement from January 1925, authorizing Reverend J. G. Taylor as the school collector. This role involved collecting funds from the community to support the school. As such, in this position, Rev. Taylor would travel around the community asking businesses and individuals to donate money to the Woodstock Industrial Institute. Reverend J. G. Taylor had an interest in farming and was also a member of the Prince Hall Freemasons, which supported Black education projects. [9] The Prince Hall Freemasons were an African-American branch of the fraternal organization originating in Boston, Massachusetts in 1784 after splitting with another Freemasons group due to racism. Part of Prince Hall’s early community work included fundraising to open schools for Black children. [10] Working as a collector for the Woodstock Industrial Institute was thereby a fitting position for Rev. Taylor.

This collecting book contains the names and donation amounts of many businesses and people who gave Reverend Taylor money or a cheque in support of the school (Figure 3). Businesses like The Royal Bank of Canada and The American Pad & Textile Co. donated to support the school. These businesses potentially supported the Woodstock Industrial Institute to gain more competitive employees by helping develop the education and working skills of the Black community. They could also donate for the simple reason of supporting the Black community in Chatham. Regardless, the list of names and businesses provides an interesting snippet at those willing to financially support a Black-led institution during this period.

Reverend Taylor held this position from the opening of the school in 1908, until he died in 1925. Only two years later, the school closed as an educational institution and transitioned into the J. G. Taylor Community Centre. [11] The naming of this community centre after Reverend Taylor demonstrates his influence on the school and community of Chatham. His involvement with the Woodstock Industrial Institute predated the school’s opening. Figure 4 shows an article from the Blyth Standard, in May 1908,stating that Taylor was there to scout locations for a future industrial school to serve the Black community. The article then mentions that Chatham became the location of the school. [12] Taylor’s efforts in scouting locations for the school as well as his authorization as collector, prove his influence on the Black community and Woodstock Industrial Institute.

The collecting book also contains signatures from leaders of the Woodstock Industrial Institute who signed the book to authorize J. G. Taylor as the collector. These names include the school’s president W. A. James, a teacher named Ms. Hodge, the secretary-treasurer James B. Richards, and the collector Reverend J.G. Taylor. These names are significant to the history of Chatham as leaders of the school because their efforts helped develop the working skills of the and overcome some of the disadvantages faced by the Black community. Furthermore, the building they owned would go on to be a community centre for almost sixty years. This information all feeds into a wider history of the Woodstock Industrial Institute as well as the challenges overcome by the Black community in Chatham, Ontario.

The colonies of Canada developed a reputation as a “Promised Land” for Black people escaping from America around the time of the American Civil War. The American system openly placed Black people below their white counterparts both in law and in culture. In contrast, laws in the Canadian colonies appeared to place Black and white people as equals. [13] However, the collecting book from the Woodstock Industrial Institute, as an artifact of the last school opened by the Black community, shows the continuing inequalities faced by Black people in Chatham. All citizens of Chatham and the province of Ontario paid taxes, which in part, funded the public school system. However, most of Chatham’s schools funded by this system did not allow for the attendance of Black children. [14] Black citizens thus paid taxes into a system that actively restricted them from using the schools funded by these taxes. This unfair practice did not sit well in the Black community, and newspapers from the mid-nineteenth century onward complain about the unfair system of public education. For example, in a newspaper article from 1843 titled, “Citation from the Colored Inhabitants of Hamilton,” the writer represents many Black residents of Ontario in stating their disdain for the Government’s refusal to allow Black children into the schools that their tax dollars actively funded. [15] To provide a proper education for their students, the Black community thus had to fund and organize schooling systems of their own. Advertisements for private schools appeared in local newspapers. One such example is Amelia F. Shadd and M. A. S. Cary’s notice from 1859 in the Provincial Freeman, titled, “School for All.” As the advertisement states, the school welcomed all children and offered a reduced price for families in poverty. [16] Shadd did not support the segregation of schools and tried to address the need for educating Black children. [17] However, private schools such as Shadd and Cary’s struggled to operate because they lacked funds. The schools continued to be overcrowded, paid teachers poorly compared to other schools, and lacked educational resources. [18] The Woodstock Industrial Institute, opened in 1908, was the last school created by the Black people for Chatham. [19] As a remnant of the Woodstock Industrial School and direct component of gathering funds for the school to ensure a strong education for its students, this collecting book is a reminder of the difficulties faced by the Black community of Chatham in a supposed “Promised Land.”

The Black community in Chatham continues to honour their history and the Woodstock Industrial Institute despite facing many setbacks along the way. One major setback is that many of the buildings relevant to Black history in Chatham are now gone. The groundswell of support and community identity needed to end segregation and lessen the impact of racism in the Black community gradually faded throughout the twentieth century. This translated into difficulties acknowledging and preserving the Black community’s history in Chatham.. In 1979, those trying to save Black history in Chatham developed plans to renovate the former Woodstock Industrial Institute, then named the J. G. Taylor Community Centre, and re-establish it as a community space. [20] Despite their best efforts, the plans failed, and by 1984 the city of Chatham tore down the building. However, the Black community resurged in the 1990s to develop a new community centre to fill the gap left behind by the J. G. Taylor Community Centre. This movement raised over four million dollars from community donations and government funding. By 1996, the new W.I.S.H Centre opened as a community space with a gym, workshops, computer facility, and museum to display the history of Chatham’s Black community. The “W” and “I” in W.I.S.H. honour the Woodstock Institute. [21] As an artifact of the Woodstock Industrial Institute, the collecting book continues to tell the story of the Black people in Chatham and their efforts to re-establish the identity and memory of their past.

As an artifact from the Woodstock Industrial Institute, this collecting book represents a wider history of Chatham’s Black community. As the last school created by the Black community, the Woodstock Industrial Institute, represented by this collecting book, embodies the history of segregated schooling in Chatham. The collecting book and school also reference the history of racism and disadvantages placed on the Black community in a supposedly equal society. Lastly, as a popular community centre and partial namesake of the new W.I.S.H Centre, the Woodstock Industrial Institute and its destruction reignited support for the support and remembrance of the Black community in Chatham. Therefore, the collecting book from the Woodstock Industrial Institute represents the history of the Black community in Chatham through the segregated history of Chatham’s schools, the difficulties faced by the Black community in a supposed “Promised Land,” and the recent efforts of the community to honour their history despite the loss of significant landmarks.

Bibliography

Charles, Peter D. Windfall….At the Forks: An Architectural Book on the City of Chatham. Chatham, ON: Chatham Local Architectural Conservation Advisory Commission, 1979.

“Citation from the Colored Inhabitants of Chatham,” October 19, 1843.

“J.G. Taylor Community Centre History.” Chatham-Kent Black Historical Society & Black Mecca Museum, March 10, 2021. https://www.facebook.com/CKBHS/posts/3736603953089644.

Jaynes, Gerald D. “Prince Hall Masons.” Essay. In Encyclopedia of African American Society, 663. Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 2005.

Kerr, J. Leslie. “Collecting.” The Blyth Standard, May 28, 1908.

Paul, Heike. “Out of Chatham: Abolitionism on the Canadian Frontier.” Atlantic Studies 8, no. 2 (June 1, 2011): 165–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/14788810.2011.563135.

Reid-Maroney, Nina, Handel Kashope Wright, Boulou Ébanda de B’béri, and Afua Cooper. The Promised Land: History and Historiography of the Black Experience in Chatham-Kent’s Settlements and Beyond. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press, 2014.

Robinson, Gwendolyn, and John W. Robinson. Seek the Truth: A Story of Chatham’s Black Community. Canada: G. & J.W. Robinson, 1989.

Semple, Neil. “Egerton Ryerson.” In The Canadian Encyclopedia, December 17, 2007. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/egerton-ryerson.

Shadd, Adrienne. “No ‘Back Alley Clique’”: The Campaign to Desegregate Chatham’s Public Schools, 1891-1893.” Ontario History 99, no. 1 (2007): 77. https://doi.org/10.7202/1065798ar.

Simpson, Donald George. “Negroes in Ontario from Early Times to 1870.” Dissertation, The University of Western Ontario, 1971.

The Woodstock Institute Sertoma Help Center. Chatham, ON: Chatham Kent Black Historical Society & Black Mecca Museum, n.d.

[1] Neil Semple, “The Canadian Encyclopedia,” in The Canadian Encyclopedia, December 17, 2007, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/egerton-ryerson.

[2] Donald George Simpson, “Negroes in Ontario from Early Times to 1870” (dissertation, The University of Western Ontario, 1971), 507.

[3] Shadd, “No ‘Back Alley Clique’,” 83.

[4] Donald George Simpson, “Negroes in Ontario from Early Times to 1870” (dissertation, The University of Western Ontario, 1971), 676-677.

[5] Adrienne Shadd, “No ‘Back Alley Clique’”: The Campaign to Desegregate Chatham’s Public Schools, 1891-1893,” Ontario History 99, no. 1 (2007): p. 77, https://doi.org/10.7202/1065798ar, 94.

[6] Gwendolyn Robinson and John W. Robinson, Seek the Truth: A Story of Chatham’s Black Community (Canada: G. & J.W. Robinson, 1989), 93-94.

[7] “J.G. Taylor Community Centre History,” Chatham-Kent Black Historical Society & Black Mecca Museum, March 10, 2021, https://www.facebook.com/CKBHS/posts/3736603953089644. Robinson and Robinson, Seek the Truth, 94.

[8] The Woodstock Institute Sertoma Help Center (Chatham, ON: Chatham Kent Black Historical Society & Black Mecca Museum, n.d.), 3. Peter D. Charles, Windfall….At the Forks: An Architectural Book on the City of Chatham (Chatham, ON: Chatham Local Architectural Conservation Advisory Commission, 1979), 32.

[9] “J.G. Taylor Community Centre History,” Chatham-Kent Black Historical Society & Black Mecca Museum, March 10, 2021, https://www.facebook.com/CKBHS/posts/3736603953089644.

[10] Gerald D. Jaynes, “Prince Hall Masons,” in Encyclopedia of African American Society (Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 2005), p. 663.

[11] The Woodstock Institute Sertoma Help Center, 2.

[12] J. Leslie Kerr, “Collecting,” The Blyth Standard, May 28, 1908, p. 5.

[13] Nina Reid-Maroney et al., The Promised Land: History and Historiography of the Black Experience in Chatham-Kent’s Settlements and Beyond (Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press, 2014), 135-136.

[14] Shadd, “No ‘Back Alley Clique’,” 85.

[15] “Citation from the Colored Inhabitants of Chatham.” October 19, 1843.

[16] Shadd, Amelia F., and M. A. S Cary. “School for All!” Provincial Freeman. January 28, 1859.

[17] Heike Paul, “Out of Chatham: Abolitionism on the Canadian Frontier,” Atlantic Studies 8, no. 2 (June 1, 2011): pp. 165-188, https://doi.org/10.1080/14788810.2011.563135, 173.

[18] Shadd, “No ‘Back Alley Clique’,” 86.

[19] Shadd, “No ‘Back Alley Clique’,” 96.

[20] Charles, Windfall….At the Forks, 32.

[21] The Woodstock Institute Sertoma Help Center, 3.