Natalie Boros

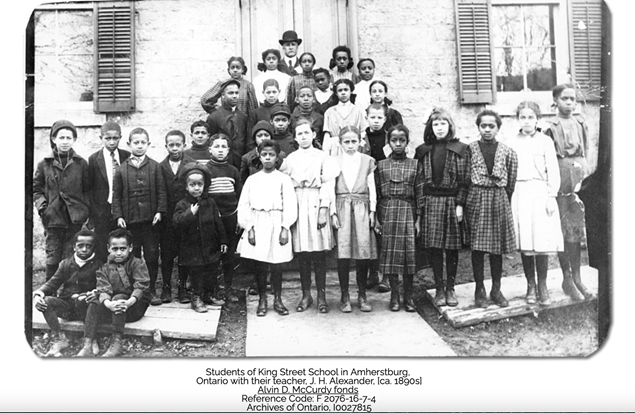

Many individuals have heard the infamous expression “a picture is worth a thousand words.” Photographs are a window into the past; nowadays, pressing a button on a cellphone allows us to instantaneously capture and preserve whatever we choose to document. In a present defined by modern technology, we tend to forget the effort, organization, and commitment invested into the production of a single photograph during the early years of photography. Who or what was worthy of this effort? What was the motive behind capturing a particular moment? These are just a few of the questions I explored once I selected a photograph from the Archives of Ontario website as the basis of my Black Ontario History Episode research project. Taken in the 1890s, the photograph depicts thirty-one students of various ages and their teacher, J.H. Alexander, standing outside of their school in Amherstburg, Ontario. My research revealed how this photograph offers a glimpse into the social progress that had been made in the time since the segregation of schools in the 1850s. However, the photograph also serves as a reminder of the many barriers that had yet to be overcome before African Canadians would be accepted into the broader Ontario community, as well as the ongoing challenges faced by these same communities to this day.

The setting of the image, as taken in front of the King Street School in Amherstburg, Ontario, is an essential aspect in understanding the experiences of the schoolchildren included in the photograph. Located less than twenty-five minutes away from the Detroit border, Amherstburg was home to an esablished Black community during the early nineteenth century, following the influx of free Black migration and the arrival of freedom-seekers through the complex abolitionist network of the underground railroad.[1] As more families settled in this region throughout the 1840s, they wanted their children to be able to attend publicly-funded schools in the district. In 1843, a group by the name of The Coloured People of Hamilton petitioned the Governor General, arguing that “we have paid the taxes and we are denied of the public schools, and we have applied to the Board of the Police and there is no steps taken to change this manner of treatment, and this kind of treatment is not in the United States, for the children of colour go to the Public Schools together with the white children.”[2] Despite these strong arguments, the requests brought forward by the Coloured People of Hamilton were dismissed. In this case, Black parents were limited to two options: forgoing their child’s education, or obtaining the funding and resources necessary to open a school that would include African-Canadians. Black communities in Ontario feared they had fled one country and risked their lives just to experience the same racism in another.

The circumstances of African Canadians only worsened following the Common School Act of 1850, when “segregated schools which had informally come into existence as a result of social pressure were now given official recognition as separate schools for Blacks; the boundaries of school districts were rearranged to ensure that the Blacks lived in the district with the separate school.”[3] Segregated schools were legitimized by the Common School Act of 1850, so that as long as a segregated school existed in the vicinity, the school board could legally force Black students to attend it while preserving public schools for white students. The Act was a continual source of contention for Black Ontario residents; only a decade prior to the photograph, a man named J.L. Dunn in Windsor attempted to send his daughter to a school intended for white children, despite the fact that she was Black.[4] A local newspaper recounted how “some of the other trustees were shocked at the idea of having their kids sitting beside coloured children,” and Dunn’s request for his daughter to attend the white school was denied.[5] As per the rules enforced by the Common School Act, Black children were only permitted to attend white schools if they were located well outside the boundaries of the nearest segregated school, which was not so in Dunn’s case.[6] This longstanding history of the struggle to obtain public education by the same means as white Canadians is crucial for understanding the experiences of the children captured in the photograph in the 1890s.

The sturdy stone walls and new-looking shutters that are seen behind the students in the photograph taken in the 1890s imply that the injustices faced by African Canadians were not always ignored by the Amherstburg community. The school is unrecognizable compared to when it first opened in the 1850s, when it was a log cabin without blackboards or chairs.[7] During his tour of Black settlements in Canada in 1856, abolitionist Benjamin Drew went so far as to describe the original school as “comfortless and repulsive” and noted how “the teacher, a coloured lady, is much troubled by the frequent absences of the pupils, and the miserably tattered and worn-out conditions of the books.”[8] Deprived of the proper funding or support from the school board or government, parents and teachers continually struggled to provide their students with the basic necessities. However, with the help and investment of several residents in Amherstburg, the community worked together throughout the years to improve the conditions of the segregated school, transforming it into what we see in the photograph.

Aside from the school’s architecture, the photograph further piqued my interest when I noticed the presence of several white students; I wanted to learn more about why they were there. If the King Street School was established because of segregation rather than out of necessity, why were white children attending one of the four segregated schools in their district? My research into the legacy of their teacher, J.H. Alexander, revealed that most, if not all of the white children in the photo likely attended the school by choice rather than out of obligation. According to a tribute published on the Amherstburg Freedom Museum website, “by providing an excellent education to his students, John Henry attracted the attention of white parents to his King Street School, where students of both races were welcome to attend.”[9] Any potential benefits that could come from attending white schools were no match to the capabilities of J.H. Alexander. Alexander became a very influential figure in the Amherstburg community and affected the lives of many through his devotion to teaching. As a mixed-race man himself, Alexander aspired to foster a learning environment inclusive for all, regardless of ethnicity – and the photograph is proof of this feat.

Without the ability to know the exact intention of the photograph – either for the purpose of a yearbook, a local or regional newspaper, or as personal memorabilia – it is impossible to determine why these specific students were photographed at this exact time. Whatever the specific reason, it attests to the school’s significance: “By the late nineteenth century the King Street School had become the hub of Amherstburg’s Black community, serving as a recreation centre and a meeting place for Sunday school classes and literary society meetings. Debates, dances, boxing matches and concerts were also held in the building.”[10] Being a community founded on resilience and perseverance, the residents of Amherstburg might have hired a photographer to document their successful students while paying tribute to the building that made their successes possible. Regardless of the intent behind the photograph, the King Street School is proof of the commitment made by previous generations to ensure their African Canadian children were provided for in spite of the limitations Ontario society tried to place on them.

It would not until 1966, another eighty years after the photograph was taken, that the last segregated school in Canada closed.[11] Although African Canadians are no longer subjected to the same form of segregation as experienced by the King Street School students, institutionalized racism still remains embedded in the curriculum, hallways, and classrooms of Canadian education. In an article published in 2008 about the education of African youth in Ontario, sociology and Equity Studies Professor George J. Stefa Dei explains how:

The issue of race and the stigmatization of students arising from their differential treatment by race (e.g., labeling and stereotyping, sorting of students, low student expectations by teacher, lack of curricular sophistication, the absence of diversity in staff representation, and the disciplining of Black bodies with suspensions and expulsions) cannot be underestimated. While we do have caring and dedicated teachers in the system, students’ narratives also point to experiences with teachers who label and stigmatize Black students. The onerous pressure this labeling puts on youth to challenge such prejudices is compounded by the fact that there are not sufficient safeguards and antiracist support measures in the schools to assist the students to deal with such problems.[12]

While I am unqualified to speak on the immense burdens that institutional racism places on Black Canadian students, it is important to remind readers of the work that is yet to be done as we celebrate the improvements that have been made. If we are to come to terms with our past, we must also acknowledge the contemporary burdens faced by members of our community today and work together to make Canada a safe space for all.

Ultimately, it is because of my investigation into the history of Amherstburg and the implications of segregated schooling that I was able to situate a single photograph into the bigger picture of Black Ontario history. This project not only taught me how a photograph can be worth significantly more than a thousand words, but how important it is to contribute to a better understanding of the past and highlight the diverse experiences of Black Canadians. While there are still many improvements to be made before we can confidently say that all Black Canadians have equal opportunities for success throughout their public education, the photograph of the 1890s serves as a reminder of the barriers overcome since the establishment of segregated schools.

Bibliography

Amherstburg 1796-1996: The New Town on the Garrison Grounds. Amherstburg, Ontario: Amherstburg Bicentennial Book Committee, 1997.

Becky. “A Tribute to John Henry Alexander.” Amherstburg Freedom Museum. September 13, 2017. https://amherstburgfreedom.org/a-tribute-to-john-henry-alexander

de b’Beri, Boulou, Nina Reid-Maroney, and Handel K. Wright, eds. The Promised Land, (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2014) doi: https://doi-org.proxy1.lib.uwo.ca/10.3138/9781442667457

“Economy and Education.” Black History, Alvin McCurdy Collection. http://www.archives.gov.on.ca/en/explore/online/alvin_mccurdy/economy.aspx.

“Petition of the ‘People of Colour’ of Hamilton to the Governor General protesting the practice of segregated schooling for Black children.” Archives of Ontario, October 15, 1843. http://www.archives.gov.on.ca/en/explore/online/black_history/murray-letter.aspx

Sefa Dei, George J. “Schooling as Community: Race, Schooling, and the Education of African Youth.” Journal of Black Studies 38, no. 3 (2008): 346-66. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40034384.

“Students of King Street School in Amherstburg, Ontario with Their Teacher, J. H. Alexander. c. 1890s.” Alvin D. McCurdy Fonds, Archives of Ontario, Amherstburg. In Archives of Ontario. http://www.archives.gov.on.ca/en/explore/online/black_history/big/big_35_students.aspx

“Windsor’s School Privileges.” Archives of Ontario, September 6, 1883. http://www.archives.gov.on.ca/en/explore/online/black_history/big/big_29_windsor_news.aspx.

[1] Boulou de b’Beri, Nina Reid-Maroney and Handel K. Wright, The Promised Land. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2014, 23.

[2] Petition of the ‘People of Colour’ of Hamilton to the Governor General protesting the practice of segregated schooling for Black children.” Archives of Ontario, October 15, 1843. http://www.archives.gov.on.ca/en/explore/online/black_history/murray-letter.aspx

[3] Amherstburg 1796-1996: The New Town on the Garrison Grounds (Amherstburg, Ontario: Amherstburg Bicentennial Book Committee, 1997), 49.

[4] “Windsor’s School Privileges.” Archives of Ontario, September 6, 1883. http://www.archives.gov.on.ca/en/explore/online/black_history/big/big_29_windsor_news.aspx.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Amherstburg 1796-1996: The New Town on the Garrison Grounds (Amherstburg, Ontario: Amherstburg Bicentennial Book Committee, 1997), 49.

[7] Amherstburg 1796-1996: The New Town on the Garrison Grounds (Amherstburg, Ontario: Amherstburg Bicentennial Book Committee, 1997), 53.

[8] Amherstburg 1796-1996: The New Town on the Garrison Grounds (Amherstburg, Ontario: Amherstburg Bicentennial Book Committee, 1997), 53.

[9] Becky, “A Tribute to John Henry Alexander,” Amherstburg Freedom Museum, September 13, 2017, https://amherstburgfreedom.org/a-tribute-to-john-henry-alexander/

[10] Amherstburg 1796-1996: The New Town on the Garrison Grounds (Amherstburg, Ontario: Amherstburg Bicentennial Book Committee, 1997), 53.

[11] “Economy and Education.” Black History, Alvin McCurdy Collection. http://www.archives.gov.on.ca/en/explore/online/alvin_mccurdy/economy.aspx.

[12] George J. Stefa Dei, “Schooling as Community: Race, Schooling, and the Education of African Youth.” Journal of Black Studies 38, no. 3 (2008): 350.