Urvi Maheshwari

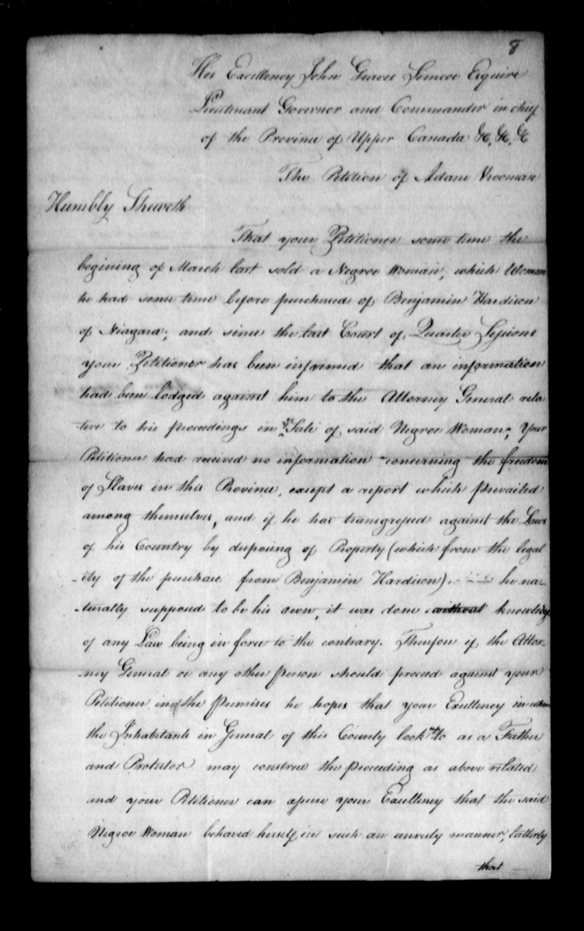

..your Petitioner has been informed that an information had been lodged against him to the Attorney General relative to his proceedings in his Sale of said Negroe Woman; your Petitioner had received no information concerning the freedom of Slaves in this Province, except a report which prevailed among themselves, and if he has transgressed against the Laws of his Country by disposing of Property (which from the legality of the purchase from Benjamin Hardison) he naturally supposed to be his own, it was done without knowledge of any Law being in force to the contrary.[1]

These are lines from a letter addressed to Sir John Graves Simcoe, the Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada from 1791 to 1796. The letter was written by Sergeant Adam Vrooman (also referred to as William), a loyalist from New York. Vrooman wrote this letter in response to charges of violence filed against him in the Court of Quarter Sessions Held at Newark in 1793.[2] (Year?) Vrooman had been accused of using violence against a Black woman enslaved by him, Chloe Cooley. As these lines demonstrate, the petition addresses the legality of his actions against Cooley, and speaks about their necessity, in light of his goal of making a sale. Vrooman wrote:

…your petitioner can assure your Excellency that the said Negroe woman behaved herself in such an unruly manner, latterly that your petitioner was under the necessity of disposing off her…[3]

This petition justifying Vrooman’s actions as an enslaver provides unique insight into the context of individual acts of resistance by enslaved women such as Chloe Cooley, and highlights the strong anti-abolitionist sentiment that prevailed in Upper Canada during this period. Cooley’s resistance to Vrooman’s actions fuelled the Act to Limit Slavery in Upper Canada, 1793, but the bill in its original form was met with significant opposition, and the Act itself was far from ideal. Vrooman’s petition serves as a prominent example of the obstacles to the abolition of slavery in late-eighteenth century Upper Canada.

The violence against Cooley at the hands of her enslaver became a controversial incident that incited the movement for abolition. On March 14, 1793, Vrooman violently bound Cooley in a boat and transported her across the Niagara River, in order to sell her in New York State. However, Cooley resisted fiercely by screaming and kicking, which forced Vrooman to enlist the help of two other men – his brother Isaac, and one of the five sons of Loyalist McGreogry Van Every – to restrain her. A week later, on March 21st, 1793, Peter Martin, a Black loyalist and veteran of the Butler’s Rangers, as well as William Grisley, an employee of Vrooman, witnessed Cooley’s resistance, an reported it to Simcoe, and other members of the Executive Council, Chief Justice William Osgoode and Peter Russel. Martin spoke of

violent outrage committed by one [Vrooman]…residing near Queens Town…on the person of Chloe Cooley, a Negro girl in his service, by binding her, and violently and forcibly transporting her across the [Niagara] River, and delivering her against her will to persons unknown”[4]

Since Martin was a Black man and a former slave, he knew the credibility of his complaint would be questioned. He brought Grisley, a white man and Vrooman’s employee who also witnessed the violence to attest to the truth of Martin’s claims. Grisley reported:

… on Wednesday evening last he was at work at Mr. Frooman’s [Vrooman] near Queens Town, who was in conversation told him he was going to sell his Negro Wench to some persons in the States, that in the evening he saw the said Negro girl, tied with a rope, that afterwards a boat was brought, and the said Frooman [Vrooman] with his brother and one Van Every, forced the said Negro girl into it…and carried the boat across the river; that the said Negro girl was then taken and delivered to a man upon the bank of the river by [Vrooman], that she screamed violently and made resistance, but was tied in the same manner…[5]

The complaint petition registered by Martin and Grisley led to charges of violence against Vrooman. However, in response to these charges, Vrooman spoke of the legality of his actions given that the purchase and sale of slaves was legal. He further suggested that the incident in March was not the only time Cooley had fought against her enslavement. She engaged in ongoing acts of resistance, behaving in “an unruly manner”: she regularly engaged in truancy and refused to work when told. Vrooman argued that Cooley’s past behaviour, and her physical struggle against her transportation and sale in March warranted violence against her. Furthermore, the petition suggests that the violence was justified since Cooley’s resistance impeded Vrooman’s ability to make the sale of his property.

The Attorney General, John White knew that the government did not have a case, since enslaved people were considered property. Additionally, an enslaved person “was deprived of all rights, marital, parental, proprietary, even the right to live”.[6] White knew that Vrooman was within his rights, and could not be prosecuted; therefore, the charges against him were dropped. Historian and Jurist William Riddell wrote: “Chloe Cooley had no rights which Vrooman was bound to respect: and it was no more a breach of peace than if he had been dealing with hisheifer.”[7] The Court’s inability to prosecute Vrooman in light of the legality of his actions demonstrate that although Cooley’s resistance was noted, it was not enough to hold Vrooman to account under existing laws.

However, despite the failure of prosecution, the Cooley episode led to the the rise of hush-toned conversations about abolition and freedom in the region. The episode of violence against Cooley became a controversial subject in the region. Although Simcoe and the authorities were unable to take legal action against Vrooman,[8] Simcoe used this episode of violence against Chloe Cooley and Vrooman’s response to the charges against him to mobilize support for the abolition of slavery in Upper Canada.

Simcoe – a strong advocate for abolition – had long been shocked to learn that many colonists in Upper Canada enslaved people, and that legislators in both chambers of the House were slaveholders. Simcoe saw the controversial Cooley incident as a means to achieve his goal of abolishing slavery.[9] He directed Chief Justice William Osgoode to draft a bill prohibiting the importation of slaves into Upper Canada.[10]

On 19 June 1793, an abolition bill was introduced to the House of Assembly by Attorney General John White. He said the bill received “much opposition but little argument” from government slaveholders. The bill was passed in the face of tremendous opposition from House representatives with slaveholding interests, who insisted that slave labour was crucial for the agricultural economy. Slaveholders within and outside the Parliament refused to give up their slaves, and Simcoe gave into the pressure. After several amendments to Osgoode’s draft, the government arrived a compromise after long negotiations, and passed An Act to Prevent the further Introduction of Slaves and to limit the Term of Contracts for Servitude or simply, the Act to Limit Slavery in Upper Canada. The bill was given Royal Assent on July 9, 1793. The preamble outlines:

Whereas it is unjust that a people who enjoy freedom by law should encourage the introduction of slaves; and whereas it is highly expedient to abolish slavery in this province so far as the same may gradually be done without violating private property…[11]

It is important to understand that despite it being a legislative success for Simcoe and his supporters, the Act was not foolproof: it secured the property rights of slaveholders who held slaves before July 9, 1793 and confirmed the position of those who were already enslaved. The Act did not free any enslaved people. Although slavery could not be expanded, it continued to function openly.[12]

However, the Act provided for children born to enslaved mothers after 1793. These children would become free on their 25th birthdays, and their children would then earn their freedom at birth.[13] On the passing of what became known as Simcoe’s Act, Simcoe said that enslaved people “may henceforth look forward with certainty to the emancipation of their offspring.” The legislation achieved two objectives. First, it prohibited the import of enslaved people into the colony, thereby repealing the Imperial Act of 1790, which allowed colonists to bring in people from Africa to work.[14] Second, it outlined that enslaved people arriving in Upper Canada from other countries would be free immediately, meaning that enslaved people were guaranteed freedom on arriving in Upper Canada.[15] The Act made Upper Canada a haven for enslaved peoples from foreign countries.[16]

The Cooley incident and resulting Act also inspired further resistance against the institution of slavery in Upper Canada. Realizing that the Act would not free them, many enslaved people in Upper Canada escaped to places like the Old Northwest Territory (Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, Minnesota, and parts of Wisconsin), and New York.[17] These were places that had either prohibited slavery or were passing legislation to do so.

The Act to Limit Slavery in Upper Canada, 1793 became the first legislation in the British Colonies to restrict slave trade. Vrooman’s response to charges of violence highlights not only the situational and environmental conditions under which enslaved people resisted, but also demonstrates the obstacles facing the movement for abolition in the region. It is notable that the resistance of one enslaved woman, Chloe Cooley was the catalyst for anti-slavery legislation and the first step towards abolition of slavery in late-eighteenth century Upper Canada.

Bibliography

Aladejebi, Funke. “Remember, Resist, Redraw #02: Chloe Cooley, Black History, and Slavery in Canada.” Active History: History Matters (Blog Post). February 24, 2017. https://activehistory.ca/2017/02/remember-resist-redraw-02-chloe-cooley-black-history-and-slavery-in-canada/

“An Act to prevent the further introduction of Slaves, and to limit the Term of Contracts for

Servitude within this Province,” 33 George IV, c.7, 9 July 1793, The Provincial Statutes of Upper-Canada,

Revised, Corrected and Republished by Authority (York: R.C. Horne, 1816).

Cooper, Afua. “Acts of Resistance: Black Men and Women Engage Slavery in Upper Canada, 1793-1803.” Ontario History, vol 19. No. 1. (2007): 5-17. https://doi.org/10.7202/1065793ar

Cruikshank, E.A. ed. The Correspondence of Lieut. Governor John Graves Simcoe, vol. 1. Toronto: The Society, 1923. https://archive.org/details/correspondenceof01simc/page/n3/mode/2up

Elgersman, Maureen. Unyielding Spirits: Black Women in Slavery in Early Canada and Jamaica. New York: Garland, 1999.

Henry, Natasha L., “Chloe Cooley and the Act to Limit Slavery in Upper Canada”. In The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Article published October 30, 2013; Accessed: November 2, 2020. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/chloe-cooley-and-the-act-to-limit-slavery-in-upper-canada

Riddell, W.R. “The Slave in Upper Canada.” The Journal of Negro History 4, no. 4 (October 1919): 372-395.

Power, Michael and Nancy Butler. “Slavery and Freedom in Niagara,” Buffalo Quarters Historical Society Papers, 1993.

Shadd, Adrienne. The Journey from Tollgate to Parkway: African Canadians in Hamilton. Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2010.

“The Petition of Peter Martin” Ontario History, Vol 26 (1930): 243. Planet Directory of the Town of Chatham, 1882. Chatham, ON: Planet Stream Printing, 1882.

“The Petition of Adam Vrooman.” Upper Canada Land Petitions, “U-V” Bundle 1, 1792-1796. (RG 1, L3, Vol. 514). Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa, ON. https://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/microform-digitization/006003-119.01-e.php?q2=29&q3=2646&sqn=1093&tt=1265&PHPSESSID=lb645d1csk2aseg41dmk5na8m0

[1] “The Petition of Adam Vrooman.” Upper Canada Land Petitions, “U-V” Bundle 1, 1792-1796. (RG 1, L3, Vol. 514). Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa, ON. https://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/microform-digitization/006003-119.01-e.php?q2=29&q3=2646&sqn=1093&tt=1265&PHPSESSID=lb645d1csk2aseg41dmk5na8m0

[2] Natasha Henry., “Chloe Cooley and the Act to Limit Slavery in Upper Canada”. In The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Article published October 30, 2013; Accessed: November 2, 2020. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/chloe-cooley-and-the-act-to-limit-slavery-in-upper-canada

[3]“ The Petition of Adam Vrooman,” Upper Canada Land Petitions.

[4] William Riddell, “The Slave in Upper Canada,” Journal of Negro History 4 (1919), 377.

[5] Ibid., 333-78.

[6] Ibid, 380.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Afua Cooper. “Acts of resistance: Black men and women engage slavery in Upper Canada, 1793-1803.” Ontario History 99, no. 1 (2007): 5-17.

[10] Ibid, 12.

[11]“An Act to prevent the further introduction of Slaves, and to limit the Term of Contracts for

Servitude within this Province,” 33 George IV, c.7, 9 July 1793, The Provincial Statutes of Upper-Canada,

Revised, Corrected and Republished by Authority (York: R.C. Horne, 1816).

[12] Afua Cooper, “Acts of Resistance,” 14-17

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid., 15.

[17] Ibid., 13.