Marion Lyons’ Quilt

Danielle Walls

Photo – Marion Lyons’ Quilt

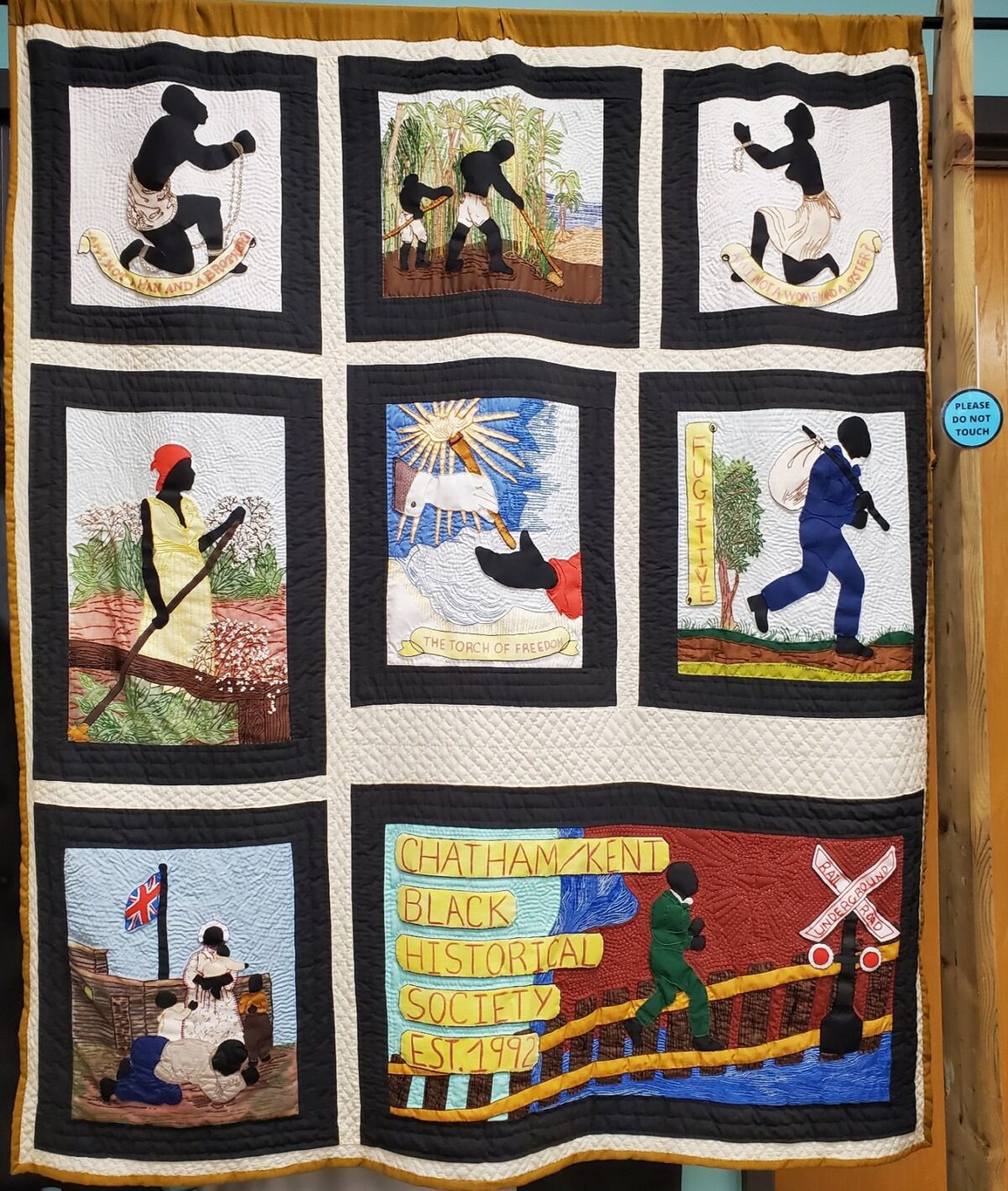

My research for this community-based project focused on the quilt created by Marion Lyons that is currently on display in the showroom of the Chatham-Kent Black Historical Society’s Black Mecca Museum. Marion Lyons was the former President of the Chatham-Kent Black Historical Society and unfortunately passed away on December 26, 2007, at the age of 66.[1] The quilt displays seven panels that each depict abolitionist imagery and Black people’s presence within the Chatham area, stimulating interest in the narratives of abolition and slavery within North America as well as the settlement of the Black population within the counties of southwestern Ontario.[2] Why did Lyons choose to create a quilt? What is its significance and purpose? Why is it hanging so prominently in the display room? The answers to these questions can be found in the role of women within Chatham’s Black community, their involvement in the abolitionist movement, and in the history and art of quilting itself.

The top left and right panels depict iconic images of the abolitionist movement. The top left is a Black man kneeling with the quote “Am I Not A Man And A Brother?” written under him in a banner.[3] The top right is a Black woman in the same pose as the man with the quote “Am I Not A Woman And A Sister?”[4] The image of the man was originally created by British potter and abolitionist, Josiah Wedgewood in 1787 as the seal for the Society for the Abolition of Slavery in England.[5] George Bourne was inspired by Wedgewood’s design and created the “Am I Not A Woman And A Sister?” image in 1838 to include women in the expanding discussion on abolition.[6]

The top, middle panel is a depiction of two enslaved men working a field. The second row (from left to right) includes depictions of a woman beside a tree that has been cut down, a white hand passing “The torch of freedom” to a black hand, and a runaway slave with “Fugitive” written vertically alongside him.[7] The third row only has two panels. The panel on the left is of a mother, father and their three children standing in front of a wood settlement with the British Flag in the background.[8] The final and largest panel on the quilt has “Chatham-Kent Black Historical Society Est. 1992” written on it alongside the image of a man running down train tracks with “Underground Railroad” sprawled across the railway crossing sign.[9] The last panel identifies the intended recipient of Lyons’ quilt along with what Chatham is most notably known for within the context of Black history in Ontario, that being a stop on the Underground Railroad. The date refers to the establishment of the Chatham-Kent Black Historical Society in 1992, so it can be safely assumed that Lyons’ made the quilt to commemorate the Society’s creation.[10]

Why did Lyons’ choose to portray abolition and Black settlement in Chatham through the medium of quilting? The answers lie in the long history of quilt making and women’s creative work in Chatham’s Black community.

Black women’s role in the family economy were essential to the success of Black settlement as well as the liberation of their people.[11] According to the 1851 Chatham census women made up 49% of the Chatham’s Black population. However, in the 1851 and 1861 censuses, the occupational status of most of these women were either not recorded or were simply listed as housewife.[12] Despite this, in the 1861 census there were 39 women artisans listed as seamstresses, likely in home-based businesses which catered to the local community.[13] The importance of sewing as a profession for Black women and its popularity amongst the women possibly explains the link between Marion Lyons’ choosing to create a quilt to gift the Chatham-Kent Black Historical Society.

Sewing and quiltmaking is an artform that continues to be used amongst African American and African Canadian women as a sociopolitical tool to form communities with each other in order to resist racism, oppression, and patriarchy.[14] Quilts as objects primarily exist in feminine spheres of artistic expression that reflect lasting, interconnected knowledge that resonates with generations of women. They are also commonly designed to “commemorate, preserve, illustrate, or express important events” within women’s lives.[15] Quilting represents matrilineal ties and knowledge that are shared and preserved amongst women within a specific community such as the Black community of Chatham.

Marion Lyons’ quilt is an example of a “story quilt” as it holds a distinct narrative and knowledge of slavery, abolition, and community. Story quilts are a form of quiltmaking used amongst African American women which combines multiple sewing methods in order to tell visual and textual tales. Some key characteristics of story quilts include the use of color, a sense of image, surface embroidery, and key words to help explain the story being presented.[16] Lyons’ quilt displays all of these characteristics from the use of colour and images, distinct surface embroidery, and key words like “Fugitive” and “The Torch of Freedom.”[17] The paneling on the quilt also progresses in a way that a story would. The top panels tell a story of abolition and slavery within North America, the middle panels depict fleeing to Canada and beginning to settle the land, and the bottom two panels show the permanent settlement of Black families within the Chatham area that leads to the eventual establishment of the Chatham-Kent Black Historical Society in 1992. Marion Lyons and her quilt are part of an ongoing tradition of African American women using the art of quilting as a means of resistance, storytelling, and sharing generational knowledge within their respective communities.

By exploring the history and meaning of quiltmaking and its relationship with Black women in North America, it is clear that Marion Lyons wished to pass on the knowledge and history of abolition and the importance of Black settlement within Chatham and the rest of Ontario. The role of women as seamstresses within the Black population contributes to framing Lyons’ quilt in a localized historical context as it signifies the sense of community that was created amongst these women and how they utilized this artform to fight for abolition and emigration to southwestern Ontario.[18] However, in the broader context of antislavery activities within North America, Lyons’ quilt is one of many that continues to tell the stories of Black people’s struggle for rights and equality. A more recent example of a quilt that tells the story of a community and their shared knowledge is the 2018 Black Lives Matter Witness Quilt which was made by Black women to remember and honour the lives of other Black women who were murdered by their partners.[19] This concludes that the practice of quiltmaking as a knowledge-based artform is still alive and well within Black, matrilineal communities.

During my research process it was difficult to think of the quilt outside of its basic history of who made it and why. However, as I continued to explore more about quilting and its ties to communities of Black women within North America, it is clear to see how material objects are able to transcend beyond their basic functionality and meaning. Such is the case for the quilt of Marion Lyons. Its basic history is that it was a quilt made to commemorate the establishing of the Chatham-Kent Black Historical Society in 1992. However, it is a part of the deeper history of abolition, resistance, and community that was fostered not only amongst the Black community in Chatham and the surrounding areas, but also in other American and Canadian Black communities. Marion Lyons’ quilt hangs on display in the showroom of the Chatham-Kent Black Historical Society because it is a small yet significant piece of Black women’s contributions to their communities. It continues to preserve the knowledge of abolition and resilience within Chatham and the rest of Ontario for future generations to learn from and contribute to.

Bibliography

Bristow, Peggy. We’re Rooted Here and They Can’t Pull Us Up: Essays in African Canadian Women’s History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1994.

Butler, Alana. “Quiltmaking Among African-American Women as a Pedagogy of Care, Empowerment, and Sisterhood.” Gender and Education 31, no. 5 (2019): 590-603.

Chatham-Kent Black Historical Society. “About Us,” The Museum, Accessed March 14, 2022. https://ckbhs.org/about/.

Higgs, Elizabeth, and Polly F. Radosh. “Quilts: Moral Economies and Matrilineages.” Journal of Family History 38, no. 1 (2013): 55-77.

Miles, Tiya. “Packed Sacks and Pieced Quilts: Sampling Slavery’s Vast Materials.” Winterthur Portfolio 54, no. 4 (2020): 205-222.

“Picture: Marion Lyons’ Obituary (CKBHS archives),” Chatham-Kent Black Historical Society, https://ckbhs.org/.

“Object: Am I not a man and a brother?,” Library of Congress Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Reference Number: 20540. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2008661312/.

“Object: Quilt made by Marion Lyons,” Chatham-Kent Black Historical Society, https://ckbhs.org/.

“Picture: Am I not a woman and a sister?,” SHEC: Resources for Teachers, https://shec.ashp.cuny.edu/items/show/1223.

[1] “Picture: Marion Lyons’ Obituary (CKBHS archives),” Chatham-Kent Black Historical Society, https://ckbhs.org/.

[2] “Object: Quilt made by Marion Lyons,” Chatham-Kent Black Historical Society, https://ckbhs.org/.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] “Object: Am I not a man and a brother?,” Library of Congress Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Reference Number: 20540. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2008661312/.

[6] “Picture: Am I not a woman and a sister?,” SHEC: Resources for Teachers, https://shec.ashp.cuny.edu/items/show/1223.

[7] “Object: Quilt made by Marion Lyons.”

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] “About Us,” The Museum, Chatham-Kent Black Historical Society, accessed March 14, 2022, https://ckbhs.org/about/.

[11] Peggy Bristow, We’re Rooted Here and They Can’t Pull Us Up: Essays in African Canadian Women’s History (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1994), 87.

[12] Ibid., 97-98.

[13] Ibid., 104, 139.

[14] Alana Butler, “Quiltmaking among African-American women as a pedagogy of care, empowerment, and sisterhood,” Gender and Education 31, no. 5 (2019): 590.

[15] Elizabeth Higgs, and Polly F. Radosh. “Quilts: Moral Economies and Matrilineages.” Journal of Family History 38, no. 1 (2013): 55.

[16] Tiya Miles, “Packed Sacks and Pieced Quilts: Sampling Slavery’s Vast Materials,” Winterthur Portfolio 54, no. 4 (2020): 217.

[17] “Object: Quilt made by Marion Lyons,” Chatham-Kent Black Historical Society, https://ckbhs.org/.

[18] Peggy Bristow, We’re Rooted Here and They Can’t Pull Us Up, 108.

[19] Alana Butler, “Quiltmaking among African-American women as a pedagogy of care, empowerment, and sisterhood,” Gender and Education 31, no. 5 (2019): 590.