Jacob Vanderhoeven

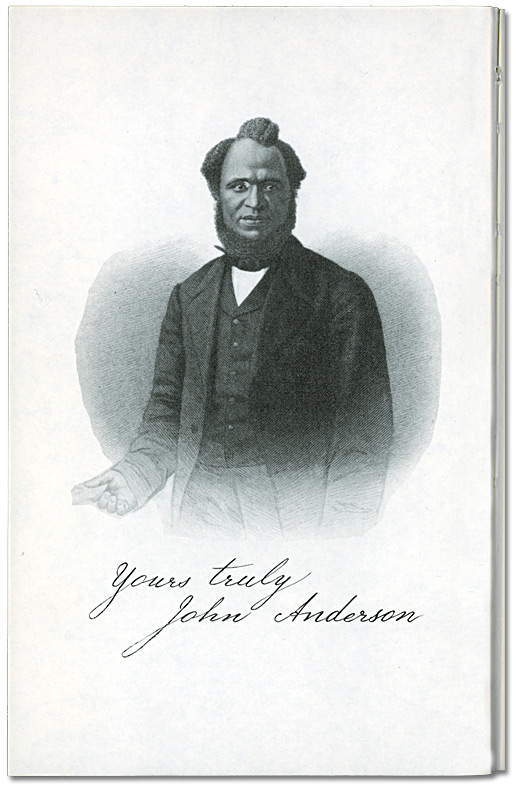

John Anderson’s portrait can tell us a lot about the lives of Black Canadians in the 19th century. Born enslaved in Missouri, John Anderson would establish a new life for himself in Chatham, Canada in 1858 after escaping from his former master. The portrait itself was engraved in England in 1863 by an abolitionist society which was interested in using Anderson as a symbol for the dehumanising nature of American chattel slavery.[1] The reveals how Black Canadians lived during the period, but also how they hoped to reshape their image in the face of harmful racial stereotypes which were pervasive throughout Canadian society. Although slavery had been abolished in 1833 by an act of British Parliament, it did not magically resolve the many prejudices Black people faced (and continue to face) in Canadian society.[2] The portrait speaks to the fierce debate which erupted over the proper place of these black migrants from the United States which was fought in Ontario classrooms, courtrooms, and even within the broader British Empire.

Who was the man who would inspire such a contentious portrait, and what did this portrait look like? Born in 1831 in Missouri into American chattel slavery, he would spend the first twenty years of his life enslaved to a planter named Jack Burton on his farm in Missouri.[3] He had grown up effectively orphaned, as his mother was sold off the farm and his father ran away while he was young.[4] Perhaps John Anderson inherited something of his father’s rebellious spirit, as in 1853 he would follow in his father’s footsteps by emancipating himself through running north to Canada.[5] According to his testimony, by 1860, he had been settled in Canada for two years, had bought a house in Niagara, and was practicing the trades of masonry and plastering.[6] As Anderson began his new life, he was unaware that his former owner was conspiring to reclaim him, and his attempt to do so would ignite a fierce debate within Canadian society over whether Canada should be a place of refuge for enslaved peoples.

The portrait, engraved from a studio photograph in 1863, depicts Anderson standing with his hand holding a piece of parchment.[7] He bears a long, serious, but somewhat solemn expression, as he looks slightly off to the side.[8] In short, he is depicted as an honest, gentle, and thoughtful man who would not look out of place in a local law office or coffeehouse in London or Kingston.

The accuracy of this depiction is doubtful. This photo was commissioned by the abolitionist society which authored his autobiography, and given their political motivations, it may represent more of an ideal rather than reality.[9] Further, there are some striking inconsistencies. For example, an earlier portrait, published in 1861 for the Illustrated London News, displays a beardless man with a round face and a far more grandfatherly and softer disposition.[10] However, what is consistent between the two images is his middle-class appearance, complete with a kind expression and fine suit.[11] The message was that Black men could become model citizens of the British Empire and that despite their traumatic pasts, the formerly enslaved could find welcome in Canadian society, a message meant to speak well of Canada’s moral character. Anderson wears a suit to represent the same sense of dignity and civility.

It was important to display escaped slaves as model citizens, since although slavery had been outlawed in Canada in 1833, the status of fugitive slaves in Canada was far from settled. In 1842, as part of the Webster-Ashburton treaty which settled Canada’s borders with the United States, provisions were made for the extradition of certain criminals. Article x of the treaty provided for the extradition of each side’s criminals if they violated any of the ten laws which were shared by both nations such as charges of murder, robbery, possession of forged papers, and assault.[12] Anderson and many other escaping slaves had been forced to result to robbery and even murder to maintain their freedom. Anderson himself had killed a white slave-hunter who had tried to bring him back to his master for a reward.[13] As a result, many free people, John Anderson included, faced the threat of extradition back to a country which did not recognise their freedom for crimes they had committed in reasserting their freedom.

This treaty was controversial in its time, with many abolitionists maintaining that it effectively opened a backdoor to American slaveowners to reclaim their former property through extradition.[14] However, this condemnation was not unanimous within Canadian society. Although not necessarily in favour of slavery, many Canadian conservatives feared that granting escaped slaves’ asylum would encourage a wave of black migration into the colony.[15] Further, the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850 in the US effectively eliminated the legal distinction between free and slave states, by enabling slave hunters and owners to bring and hunt their slaves throughout the US. This development was not lost on Canadian abolitionists, who encouraged formerly enslaved peoples to stay in Canada where their freedom was secured rather than living in the United States after the passage of the Act.[16] As a result, local Ontario officials were often caught between the desires of abolitionist and conservative factions.

Naturally, many Black leaders and their white, abolitionist allies sought to seek ways to present themselves as model British patriots in the face of conservative skepticism. The image of John Anderson as a gentle and sophisticated man presented in the picture certainly played a role in this larger conflict. For example, in 1852, a Black man named Dennis Hill wrote to the superintendent for Schools for Upper Canada (and father of the Residential Schools) Reverend Egerton Ryerson to argue that his son be admitted into the common schools. Hill, like Anderson in his portrait, presented himself as a middle-class man, who owned substantial tracts of land and was within one of the largest tax brackets.[17] Although this attempt was unsuccessful, the argument fits within the larger theme of Black men attempting to earn acceptance within Canada through presenting themselves as ideal, middle-class British patriots.

Lastly, the portrait of John Anderson is notable for his solitary nature. Anderson is the only person in the image, and this effectively severs his link with perhaps the greatest sources of support available to him, the Black community. For example, during an earlier extradition case, the Black community had unified behind their pastor to prevent the extradition of Solomon Moseby to Kentucky. Moseby was accused of stealing a horse on his escape north to Canada, and many feared that if he was extradited to the States, his former owner would exploit an opportunity to enslave him again. During the trial, the Black community held a vigil, and when the authorities decided to extradite him, their protests enabled Moseby to escape from Canadian authorities and avoid extradition.[18] It was through the black community’s efforts that the defendants in these extradition trials were provided with lawyers and forms of informal support which often prevented them from being easily extradited by Canadian authorities.

However, the solidarity expressed by the Black community was not unique to extradition cases, nor was it limited to Canadian affairs. As the Black community attempted to assert its rights to the full benefits of British freedom, they were careful to establish meaningful links between Canadian communities and other communities throughout the British Empire. For example, utilising their common experiences with imperial rule, Black communities in both the East Indies and the Canadian colonies joined forces to draft and send petitions to request government funding to build schools and gain legal protections from extradition.[19] However, even in expressing bonds forged by the rigours of imperial rule, these sentiments were often framed through patriotic expressions. For example, in both Jamaica and Chatham, Canada the Black community hosted annual celebrations of the Act to Abolish Slavery on August 28th in a similar manner to how many Black Americans celebrate Juneteenth.[20] Through these celebrations, Black communities throughout the British Empire managed to consolidate this newfound sense of solidarity and pride in a socially acceptable manner.

Thus, although the portrait of John Anderson which I investigated in this post may not have represent the man accurately, it did strike a far deeper and more controversial reality. In the image, we see how self-emancipated men and women attempted to cast themselves as model British citizens to distance themselves from their lives as enslaved peoples. Through, the development of strong links throughout the British Empire and Black diaspora, Black communities were able to establish strong support groups that would stand up for them when the Canadian government would not. Thus, John Anderson’s story and portrait demonstrate that escaping to Canada was only a significant step in a far longer and incomplete journey towards acceptance by Canadian society at large.

Bibliography

Act of Abolition of Slavery, Statute of the United Kingdom 1833, c. 73. http://www.archives.gov.on.ca/en/explore/online/black_history/big/big_02_imperial_act.aspx

Asuka, Ikuko. “Our Brethren in the West Indies”: Self-emancipated People in Canada and the Antebellum Politics of Diaspora and Empire.” The Journal of African American Studies. (2012): 219-239.

Brode, Patrick. The Odyssey of John Anderson. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1989.

Finkelman, Paul. “International Extradition and Fugitive Slaves: The John Anderson Case.” Brooklyn Journal of International Law vol 18, no 3, (1992): 765-810.

Girard, Philip, Jim Phillips and R. Blake Brown. A History of Law in Canada: Volume One. Toronto: Toronto University Press, 2018.

Hill, Dennis. “Dennis Hill to Rev. Egerton Ryerson”, November 22, 1852, The Ontario Archives, http://www.archives.gov.on.ca/en/explore/online/black_history/dennis-hill-letter.aspx.

Illustrated London News. vol. 38, no. 1078, p. 223. Published in March 9, 1861.

Murray, David. “Hands Across the Border: The Abortive Extradition of Solomon Moseby.” The Canadian Review of American Studies vol. 30, no 2. (2000): 187-209.

Portrait of John Anderson. In the Archives of Ontario. Accessed October 31, 2020. http://www.archives.gov.on.ca/en/explore/online/black_history/big/big_12_john_anderson.aspx

Thomas, Harry. Summary of The Story of the Life of John Anderson, the Fugitive Slave. Documenting the American South. Accessed April 6, 2021. https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/twelvetr/summary.html.

Webster-Ashburton Treaty”. Signed on August 9, 1842. Yale University’s Avalon Project: Documents in Law, History and Diplomacy vol. 4. (1934): 80-121. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/br-1842.asp

Wickham, S. S. Wickham to D.B. Stephenson. October 12, 1850. In the Archives of Ontario. Accessed October 31, 2020. http://www.archives.gov.on.ca/en/explore/online/black_history/freedom.aspx

[1]Harry Thomas, “Summary of The Story of the Life of John Anderson, the Fugitive Slave,” Summary of The Story of the Life of John Anderson, the Fugitive Slave (Documenting the American South), accessed April 6, 2021, https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/twelvetr/summary.html.

[2]Act of Abolition of Slavery, Statute of the United Kingdom 1833, c. 73. http://www.archives.gov.on.ca/en/explore/online/black_history/big/big_02_imperial_act.aspx

[3]Patrick Brode, The Odyssey of John Anderson, (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1989), 4

[4]Ibid., 2.

[5]Ibid., 7.

[6]Paul Finkelman. “International Extradition and Fugitive Slaves: The John Anderson Case.” Brooklyn Journal of International Law vol 18, no 3, (1992): 766-7.

[7]Portrait of John Anderson, in the Archives of Ontario, Accessed October 31, 2020. http://www.archives.gov.on.ca/en/explore/online/black_history/big/big_12_john_anderson.aspx

[8]Ibid.

[9]Thomas, “Summary of the story of the life of John Anderson, a fugitive slave,” https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/twelvetr/summary.html

[10]Illustrated London News. vol. 38, no. 1078, (March 9, 1861): p. 223.

[11] Finkelman, International Extradition and the slave trade, 766-767

[12]The Webster-Ashburton Treaty” Signed in August 9, 1842, Yale University’s Avalon Project: Documents in Law, History and Diplomacy vol. 4, (1934): 80-121. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/br-1842.asp

[13]Brode, The Odyssey of John Anderson, 12.

[14]Finkelman, International Extradition and the slave trade, 765-766.

[15]Philip Girard, Jim Phillips, and R. Blake Brown, A History of Law in Canada: Volume One, (Toronto: Toronto University Press, 2018), 671

[16]S. S. Wickham, “Wickham to D.B. Stephenson”, October 12, 1850,. In the Archives of Ontario. Accessed October 31, 2020. http://www.archives.gov.on.ca/en/explore/online/black_history/freedom.aspx

[17]Dennis Hill, “Dennis Hill to Rev. Egerton Ryerson”, November 22, 1852, The Ontario Archives, http://www.archives.gov.on.ca/en/explore/online/black_history/dennis-hill-letter.aspx

[18]David Murray, “Hands Across the Border: The Abortive Extradition of Solomon Moseby.” The Canadian Review of American Studies vol. 30, no 2, (2000): 187-188.

[19]Ikuko Asuka. “Our Brethren in the West Indies”: Self-emancipated People in Canada and the Antebellum Politics of Diaspora and Empire,” The Journal of African American Studies, (2012): 222.

[20]Asuko, Our Brethren in the West Indies, 224-225.