Dayna Vreman

Photo Courtesy of the Ingersoll Cheese and Agricultural Museum

In the above photograph, two people of African descent, a husband and wife, stand side by side in front of their small but well tended home.[1] Their plot of land is heavily cultivated with trees, flowers and vegetables, closed off from the outside road by a simple wire fence. While it is difficult to see their facial expressions, their posture is confident, suggesting a quiet but firm pride in the property they own. Looking at this photograph inspires many questions such as: who were these people, or what were their lives like? The answers are surprisingly plural. In fact, there are two competing narratives regarding the identity of the couple. If one were to ask the Ingersoll Cheese and Agricultural Museum, which owns the photograph, the couple would be tentatively identified as Reverend Solomon Peter Hale and his wife, Joanna, who lived in Ingersoll.[2] On the other hand, the Elgin County Museum and Archives identifies the couple as Lloyd Graves and his wife, Amanda Graves who lived around Mount Salem. Which narrative is true? Can they both be plausible?

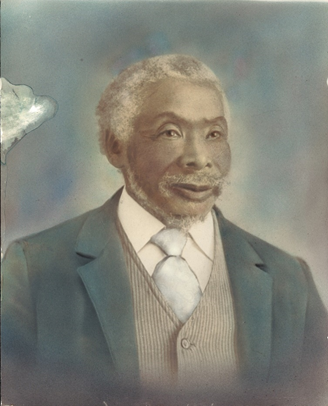

Lloyd Graves. Photo Courtesy of the Aylmer-Malahide Museum and Archives

The two different stories attached to this photograph likely result from the fact that the photographers, the Hugill family, had family members that lived in Ingersoll and St. Thomas.[3] According to Scott Gillies, the curator of the Ingersoll Cheese and Agricultural Museum, John Hugill moved to St. Thomas from Ingersoll in the 1880s where he and his son, Rondeau Bertram Hugill, ran a photography studio.[4] Around the same time, George Alfred Hugill and Ashton Hugill, who operated a drug store in Ingersoll, also became photographers.[5] If the photograph was taken by John and Rondeau, it would likely be depicting the Graves family who lived closer to St. Thomas. On the other hand, if the photo was taken by George or Ashton, it would most likely depict the Reverend Hale and his wife. The question over which Hugill took the photograph and therefore who is depicted in said photograph is unfortunately left a mystery. For the purposes of this project, I have chosen to focus on Lloyd Graves and his wife, Amanda, about whom much more is known.

The lives that Lloyd and Amanda led were dramatic, filled with both hardship and triumph, and intricately tied to themes of slavery, resistance, and freedom. Both Amanda and Lloyd had a connection to slavery. Amanda was born in Canada but was the daughter of a fugitive slave[6] and Lloyd himself was born into slavery in Kentucky in roughly 1836-1837.[7] Upon hearing that he was to be sold “down south” Lloyd began planning a means of escape.[8] He escaped together with George Hamilton and used the clandestine routes of the underground railroad to evade capture.[9] His flight from slavery took him to Cleveland Ohio, where he boarded a steamer and rode it across lake Erie to Port Stanley.[10] Upon reaching Canada in 1854, Lloyd settled in St. Thomas and worked as a driver for Lindop’s Grocer.[11]

Lloyd’s tale of resistance did not end upon his entry to Canada in 1854. In fact, five years later, in 1859, Lloyd was confronted by a former master along with his fellow escapee, George Hamilton, on Talbot Street of St. Thomas.[12] The confrontation was prompted by a series of letters sent between George Hamilton and his former master, John Barton, requesting money to supposedly pay his way back to Kentucky. In his correspondence, Hamilton, with the help of another man, B. Stewart, claimed that he was “tired of the collered [sic] people’s freedom in Canada” and that he regretted leaving Kentucky.”[13] Hamilton’s letter was apparently convincing because his former master sent thirty Ohio dollars to St. Thomas to pay for his fare home.[14] The initial success of Hamilton and Stewart’s scheme enticed them to try to swindle more money out of Barton. Stewart wrote back to John Barton on behalf of George Hamilton with the tragic news that Hamilton had gotten very sick and that most of the money was used to pay his medical fee.[15] The letter requested more money so that once Hamilton got better, he could afford the journey home. No more money was to follow and after a few more exchanges requesting more money, Barton evidently became suspicious. In October of 1859, he sent a Mr. Williams up to check on the situation.[16] In the entirety of the exchange, Lloyd Graves was only mentioned in passing: “…one of John L. Graves’ servants named Loyd [sic] is here, and has written to him and expects to be able to return home when we do.”[17] Despite only playing a minor role in the scheme, Lloyd was confronted by a his former master and asked to come back. He was offered a horse and bridle, but he replied with a stiff refusal.[18] Like all other fugitive slaves, Lloyd valued his freedom.

Amanda Graves. Photo Courtesy of the Almer-Malahide Museum and Archives

Lloyd Graves did not remain in St Thomas for long. His dream was to work on a farm and own his own land. As shown by the photograph, he accomplished his dream. Lloyd obtained a property of three or four acres on the second concession of Malahide and paid for it within two years.[19] While Lloyd spent most of his life working for his neighbors, he was also able to cultivate his own land. He grew many fruit trees as well as various vegetables including corn, potatoes, and cabbage.[20] Lloyd’s produce was known county wide as he was a large exhibitor at surrounding Fall Fairs.[21]

Lloyd’s dream of owning land was shared by many other former slaves. In fact, owning land held special significance for them. For generations, slaves had been tied to the land: planting, cultivating, and harvesting its bounty, however, as slaves, they were unable to reap the profits of their own hard work.[22] The ability to benefit from one’s own work was highly attractive and therefore, land ownership came to be viewed as a new beginning for former slaves.[23] Self sufficiency was another reason why land ownership was highly valued in the Black community in Canada. Leading figures in the Southwestern Ontario Black community like Mary Ann Shadd Carey stressed the importance of owning and cultivating land, claiming that it promoted the financial independence and therefore general welfare of Black refugees.[24] In her pamphlet, A plea for emigration, or, Notes of Canada West : in its moral, social, and political aspect; with suggestions respecting Mexico, West Indies, and Vancouver’s Island, for the information of colored emigrants (1852), Mary Ann Shadd Carey spent a significant portion of time discussing climate, soil quality, and crop yields with the expectation that her brethren could become fully independent through working their own land.[25]

Self sufficiency was a moral imperative for the Black community who believed that through hard work and independence, people of African descent would be uplifted in the eyes of whites. Land ownership itself was a way to resist slavery since it suggested Blacks were legally equal to whites and proved that former slaves could be industrious and independent.[26] Black settlements in Ontario like Buxton set up strict rules to prove their respectability. For example, all houses in the Buxton Settlement were required to meet a certain standard and citizens were expected to be hard working and morally righteous (i.e. sober).[27] Residents of Buxton argued that, “The cry that has been often raised, that we could not support ourselves , is a foul slander, got up by our enemies, and circulated both on this and the other side of the line, to our prejudice. Having lived many years in Canada, we hesitate not to say that all who are able and willing to work, can make a good living.”[28] They set out to prove that given freedom, Blacks could be productive, self sufficient, and morally upright just like whites. Indeed, Lloyd’s attitude to hard work and his industrious nature earned respect from other members of the community. In several different sources, he was called a good citizen and viewed in high esteem.[29]

Following the American Civil War and the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment, many Black immigrants chose to return to America to reconnect with their family and friends. The Black communities which had sprouted up in Canada begun to dwindle. Communities that had once thrived with a large Black population such as Wilberforce or the Dawn Settlement shrank and eventually faded into obscurity.[30] Even communities that saw a growth of population were still largely transitory in nature. A good example of this was the Black community in London Ontario. In the 1868-1869 and 1878-1879 London City directories, people of African descent were demarcated by the abbreviation “col’d” or “col” (for coloured).[31] In the 1868-69 directory, 36 people were listed as “col’d” and this number increased to 53 in 1878-1879.[32] However, only 12 of those original 36 people were recorded in both directories which indicated that London was not seen as a final destination for many Black Canadians.

Lloyd Graves and his family stood in stark contrast to this trend because both he and his wife chose to live out the remainder of their lives in Canada, lives that were not at all easy. Lloyd and Amanda went through many hardships. They lost eight of their children to disease and injury, in 1892 a fire destroyed their barn and its contents, and Lloyd himself became sick with la grippe (influenza) and inflammation of the lungs.[33] Nevertheless, Lloyd and Amanda remained in Canada until their deaths. Lloyd died in 1928 and Amanda passed in 1939.[34] Their lives offer an interesting snapshot of Ontario’s Black history as they were deeply interwoven with themes of slavery, resistance and freedom.

Bibliography

“Additional Locals” Aylmer Sun, January 18, 1894.https://inmagic.elgin.ca/ElginImages/ archives/Images Archive/pdfs/A-SU-002_1894.pdf.

Ancestry.com, 1871 Census Of Canada, 1871, (Roll C-9899; Page: 58; Family No: 223) Malahide, Elgin East, Ontario Census records, Ancestry.com Operations Inc, Provo, UT, USA.

Brown-Kubisch, Linda. The Queen’s Bush Settlement: Black Pioneers, 1839-1865. Dundurn, 2004.

“Coloured Rascality” The Weekly Dispatch: St. Thomas and County of Elgin General Advisor, October 27, 1859. https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=BqipwSGYUEgC&dat=1 8591027&printsec= frontpage& hl=en.

Hugill, Photographer. “Untitled Photograph”. Photograph. Ingersoll: Hugill Photography, unknown date. From Ingersoll Cheese and Agricultural Museum.

Johnson Bruce “Lloyd Graves.” Find a Grave. Accessed March 9, 2021, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/173384245/lloyd-graves.

Landon, Fred, and Karolyn. Smardz Frost. 2009. Ontario’s African-Canadian Heritage: Collected Writings by Fred Landon, 1918-1967 Toronto: Natural Heritage Books.

Landon, Fred. “The Buxton Settlement in Canada.” The Journal of Negro History 3, no. 4 (1918): 360-67. doi:10.2307/2713816.

“Lloyd Graves passes in his 105th year,” Aylmer Express, March 8, 1928. https://inmagic.elgin. ca/ElginImages/archives/ImagesArchive/pdfs/A-EX-016_1928.pdf

London and Middlesex County Directories 1856-1881. Elgin County Microfilm Collection (MF-100), microfilm edition, Room 105, D12. Special Collections, Elgin County Archives.

Museum of London, Black History Tour: London and Southwestern Ontario, London, Ontario: Museum of London, 2004.

Schweninger, Loren. 1990. Black Property Owners in the South, 1790-1915 Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Shadd, Mary A., Notes of Canada West in its moral, social, and political aspect: with suggestions respecting Mexico, West Indies, and Vancouver’s Island for the information of colored Emigrants. Detroit: George W. Pattison, 1852; Canadiana by CRKN. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/ oocihm.47542/3?r=0&s=1.

[1] Hugill, Photographer. “Untitled Photograph”. Photograph. Ingersoll: Hugill Photography, unknown date. From Ingersoll Cheese and Agricultural Museum.

[2] Scott Gillies, email message to Dayna Vreman, March 23rd, 2021.

[3] Ibid.

Information on the Hugill family is taken from David Gibson in his 1990 publication The Hugill Chronicles: A Mosaic – Father and Son, Photographers 1860-1900.

[4]Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Profile photographs, General Interest-Amanda Graves, 1934, 2008-01, R8 S4 Sh5 B1 69, St. Thomas Times-Journal Fronds, Elgin County Archives, St. Thomas, Ontario (hereafter cited as Profile photographs, St. Thomas Times-Journal Fronds).

[7] 1871 census Of Canada, 1871, (Roll C-9899; Page: 58; Family No: 223) Malahide, Elgin East, Ontario Census records, Ancestry.com Operations Inc, Provo, UT, USA.

[8] Fred Landon, and Karolyn. Smardz Frost. 2009. Ontario’s African-Canadian Heritage : Collected Writings by Fred Landon, 1918-1967 (Toronto: Natural Heritage Books), 134.

[9] For a detailed description of Lloyd’s escape from Kentucky, see Landon and Frost, Ontario’s African Canadian Heritage, 134-136.

As an important side note, Landon refers to Lloyd’s comrade as George Barton, giving him the same last name as his former owner, John Barton. On the other hand, I have chosen to address George as George Hamilton since it is more likely that George adopted this last name instead. In his correspondence with his former master, George signs his name as ‘George Hamilton.’

[10] Landon and Frost, Ontario’s African Canadian Heritage, 136.

[11] Ibid., 134,137.

[12] Ibid., 137.

[13] “Coloured Rascality” The Weekly Dispatch: St. Thomas and County of Elgin General Advisor, October 27, 1859. https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=BqipwSGYUEgC&dat=18591027&printsec=frontpage& hl=en (Accessed March 16, 2021).

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Profile photographs, St. Thomas Times-Journal Fronds., also Landon and Frost, Ontario’s African Canadian Heritage, 137.

[20] Landon and Frost, Ontario’s African Canadian Heritage, 137., also Profile photographs, St. Thomas Times-Journal Fronds.

[21] “Lloyd Graves passes in his 105th year,” Aylmer Express, March 8, 1928. https://inmagic.elgin.ca/ElginImages/archives/ImagesArchive/pdfs/A-EX-016_1928.pdf (Accessed March 11, 2021).

[22] Loren Schweninger, 1990. Black Property Owners in the South, 1790-1915 Urbana: University of Illinois Press. 145.

[23] Ibid., 145.

[24] Shadd, Mary A., Notes of Canada West in its moral, social, and political aspect: with suggestions

respecting Mexico, West Indies, and Vancouver’s Island for the information of colored Emigrants.

(Detroit: George W. Pattison, 1852; Canadiana by CRKN). https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm. 47542/3?r=0&s=1. 8.

[25] Ibid., 8.

[26] Linda Brown-Kubisch, The Queen’s Bush Settlement: Black Pioneers, 1839-1865. Dundurn, 2004. 8.

[27] Fred Landon, “The Buxton Settlement in Canada.” The Journal of Negro History 3, no. 4 (1918): 360-67. doi:10.2307/2713816. 363.

[28] Shadd, Notes of Canada West, 32.

[29] “Lloyd Graves passes,” Aylmer Express, March 8, 1928., See also: “Additional Locals” Aylmer Sun, January 18, 1894. https://inmagic.elgin.ca/ElginImages/archives/ImagesArchive/pdfs/A-SU-002_1894.pdf.

[30] Museum of London, Black History Tour: London and Southwestern Ontario (London, Ontario: Museum of London, 2004).

[31] London and Middlesex County Directories 1856-1881. Elgin County Microfilm Collection (MF-100), microfilm edition, Room 105, D12. Special Collections, Elgin County Archives.

[32] Ibid.

[33] “Additional Locals,” Aylmer Sun, January 18, 1894.

[34] “Lloyd Graves,” Find a Grave, Bruce Johnson, accessed March 9 2021, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/ 173384245/lloyd-graves.