History of the American Methodist Episcopal Church

The building known in London as the “Fugitive Slave Chapel” was founded as part of the Canadian circuit of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. The following essay provides historical background on the denomination, and its important place in the struggle for the abolition of American slavery and the struggle against racial oppression in the United States and Canada.

A Brief History of the A.M.E Church in the United States and Canada

By: W. Craig Charteris

Following the American Revolution, America experienced a religious change that saw the emergence of Methodist Episcopal Church. Occurring from 1780 to the 1840’s the Second Great Awakening gave birth to the Methodist religion. This religious revival swept the United States bringing thousands of white Christians to the evangelical denominations such as the Methodist and Baptist.[1] Methodism in particular experienced rapid growth and increased popularity during the Second Great Awakening. By 1850 the Methodist had become the largest religion in America with over a million members and eight thousand local preachers. [2] Through the religious revivals of the Second Great Awakening, Methodism was the dominate religion in the United State and was practiced across the country, by all members of the nation.

Methodism’s popularity was a result of its broad acceptance of members into its congregation. It was a religion that disregarded class or race, unlike the hierarchical Protestant Church. Due to its wide disregard for race many African Americans were drawn to Methodist Episcopal Church; with some becoming preachers within the church.[3] African Americans’ had a presence in the Methodist Episcopal Church from its beginning. One of the reasons for the Methodist Episcopal Church’s appeal to black American’s was the church’s strong opposition to slavery.[4] As many slaves were allowed practice religion, either by attending the white churches of their master or black churches pastured by white clergy men, the Methodist Episcopal Church and its abolitionist stance drew many slaves. This brought many black members to the Methodist Episcopal Church and by 1786 African Americans composed ten present of the church’s members.[5] The African Americans, like many others were drawn to the Methodist Episcopal Church for its acceptance of all races and classes. Accompanied by the churches stance on slavery, a large number African Americans became members of the Methodist Episcopal congregation. From this the roots of African Episcopal Methodist Church (AME Church) are established.

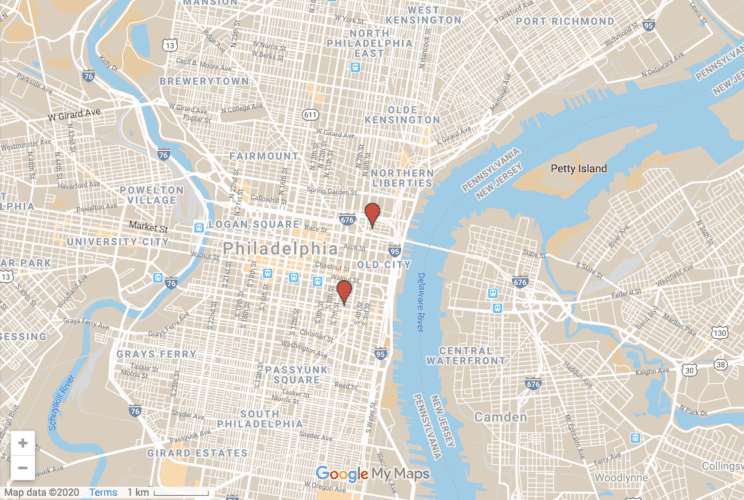

The AME Church began with a conflict between members of its congregation. Although the Methodist Episcopal Church expressed religious acceptance, the white members often discriminate towards the black members of the church. In November of 1787 Richard Allen, Absalom Jones and other black members of the St. George Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia (see map) withdrew from the church due to the discrimination by the white members.[6] Allen and his followers continued to practice the Methodist Episcopal teaching despite not having a place to practice. This lead to the Free African Society ( created by Allen and Jones) which assumed regular religious functions at the Friends Free African School House from 1788 to 1791.[7] Through this establishment Allen and his followers introduce the concept of an African America Episcopal denomination. It gave the persecuted black members of the Episcopal Church a safe place in which they were able to practice Methodism. However, this was not a permanent solution to the black Methodist’s ailments. Richard Allen recognized this and using his own funds he established the first place of worship for African Methodists on his own land, naming it the Bethel Church (see map). [8] Although the African Methodist now had a place to worship the Bethel Church was not recognized by the greater Methodist Episcopal Church. In 1816 a conference that consisted of representatives from Philadelphia, and other African churches in Baltimore, Maryland, Wilmington, Delaware, and Salem, New Jersey, met in Philadelphia and officially formed a church organization under the title of “The African Methodist Episcopal Church.”[9]

By formally establishing under the AME Church, the African Methodists was able to extend their influence. For example the Bethel Church and many other AME Church’s functioned as important points of the underground rail road; Charleston, South Carolina’s AME Church had over four thousand of its members deeply involved in slave insurrection of 1822. [10] The activism of AME Church’s in Underground Railroad lead to church branching into Canada with the slaves and members who traveled through the church to Canada. In the 1820’s the AME Church was already beginning to establish in Canada and by the 1828 there were four AME centers operating within the country.[11] The AME Church continued to expand over the next twenty years establishing all across Upper Canada. London was one of the black communities where an AME Church was established and in 1847 land was purchased for the establishment of an AME Church. [12] As the AME Church increased its presence in Upper Canada it started to want an independent identity from the American AME Church. The movement towards a church with a separate name from the AME Church was first brought to the attention of the AME Churches delegates in 1854. The Canadian Conference of the AME church which was held in Chatham that year saw the Rev. Benjamin Stewart who advocated “to set us [the Canadian AME Church] apart as a separate body.’[13] This began the eventual separation of the Canadian AME Church, from its AME name. Over the next two years the AME Church in Canada remained under its American identity, however the AME General Conference in 1856 would see the end of the AME Church in Canada. After six days of deliberation the delegates of the AME Church granted the separation of the church in Canada and on September 29, 1856 after seventeen years the AME Church in Canada was no longer under the American AME Church. [14] After the Church in Canada became a separate body there was a need to unify under a new name and identity. On October 1856 the delegates determined by majority to be named the “ British Methodist Episcopal Church” and a day later the first Annual Conference of the B. M. E. Church was held.[15] Although the B.M.E . Church was now a separate entity to the A.M.E. Church, it continued to follow the Methodist teaching brought by the Second Great Awakening and it remained a central player in the liberation of African Americans from the United States.

[1] Eric Fonger, “Give me Liberty,” Seagull Forth Edition (2014): 341-344.

[2] Nathan O. Hatch, “The Puzzle of American Methodism,” Church History: Studies in Christianity and Culture 63, (2): 175-189.

[3] Ibid.

[4] C. Eric Lincoln and Lawernce H. Momiya, The Black Church in the African American Experience (United States of America: Duke University Press, 1990),50.

[5] Ibid.

[6]Rev. N. C. W. Cannon, “A History of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the Only One in the United States of America, Styled Bethel Church.” Documenting the American South. (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 2000). http://docsouth.unc.edu/church/cannon/cannon.html

[7] C. Eric Lincoln and Lawernce H. Momiya, The Black Church in the African American Experience (United States of America: Duke University Press, 1990),57.

[8] Rev. N. C. W. Cannon, “A History of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the Only One in the United States of America, Styled Bethel Church.” Documenting the American South. (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 2000). http://docsouth.unc.edu/church/cannon/cannon.html

[9]Richard R. Wright ,”1816 -1916 CENTENNIAL ENCYCLOPAEDIA OF THE African Methodist Episcopal Church,” Documenting the American South. (Book Concern of the A. M. E. Church 631 Pine Street, Philadelphia, PA, 1916). http://docsouth.unc.edu/church/wright/wright.html

[10] . Eric Lincoln and Lawernce H. Momiya, The Black Church in the African American Experience (United States of America: Duke University Press, 1990),52.

[11] Dorothy Shadd Shreve, The AfriCanadian Church:A Stabilizer(Ontario, Canada: Paidiea Press, 1983),78.

[12] History of Fugitive Slave Chapel site. Museum of Ontario Archeology, 2013. http://archaeologymuseum.ca/fugitive-slave-chapel-site/

[13] Dorothy Shadd Shreve, The AfriCanadian Church:A Stabilizer(Ontario, Canada: Paidiea Press, 1983), 80-81.

[14] Payne, Daniel Alexander, 1811-1893 ,Smith, C. S. (Charles Spencer), 1852-1923, Ed , “Recollections of Seventy Years: Electronic Edition.” http://docsouth.unc.edu/church/payne70/payne.html

[15] Ibid.