| I. INTRODUCTION

Indigeniety is a term that has been used as a distinction between those who are “native” from “others” in specific locations[1]. The Indigenous peoples of what is now Canada trace back for thousands of years, whereas the first white settlers from Europe arrived in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Many of these newcomers believed that First Nations peoples were uncivilized savages and needed to be tamed, educated, and assimilated into white society, beliefs, and ways of life. This paper focuses on the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, where Anglophone missionaries’s interest transitioned from being primarily interested in learning Indigenous language as a tool to convert North American peoples to Christianity, to, in the 1840s and 50s, a focus on English, and less common, French, instruction. Kanien’kehá:ka are the eastern-most Indigenous nation of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. They are more commonly known as Mohawk, but this paper will address them as Kanien’kehá:ka because this is their traditional name. Although this paper focuses on the attempted erosion of Indigenous culture, it was just that; attempted. Kanien’kehá:ka people managed to keep their unique culture and traditions, and as such, will be called by their proper name throughout their paper. Literacies will be a key component within the historiographical arguments of this paper. Germain Warkentin’s phrase “objects of knowledge transfer” will be used synonymously with literacies to refer to ‘many different types of objects used by native peoples to record and transfer knowledge’[2]. The term literacies can be applied broadly in an Indigenous context to include objects and symbols like wampum belts, clan signs, syllabic script, art, and writing. Rooted in Canada’s history and succeeding historiography is the treatment of the Indigenous peoples, and how, as a country, the past has been dealt with and the future is looked upon. This paper is written with the understanding that both language and literacies are central to the longevity of a culture. Though missionaries tried to assimilate and erode the culture of the Kanien’kehá:ka peoples, this paper will also discuss how they were resilient to the nefarious attempts of European missionaries. Huron College and Weldon’s ARCC Rare Book Collections hold clear evidence and demonstrate white missionary attempts to transform Indigenous societies, erode their culture, and encourage their conversion to Christianity and European lifestyles. The motives of the missionaries were twofold; through assimilation and cultural conversion, they were part of European efforts to colonize Indigenous land, while also attempting to civilize people that they considered ‘savages’ to deliver them from sin and consequence and bring their salvation. The European missionaries that tried to convert and assimilate Indigenous peoples to Christianity targeted Indigenous language and literacy. This paper argues the Rare Book Collections best demonstrates the struggles that Kanien’kehá:ka faced in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and their continuing resistance to these colonial efforts. II. LANGUAGE AND LITERACIES Huron and Western’s Rare Book Collections demonstrates the diverse strategies European colonialists used to assimilate Kanien’kehá:ka people. They fit within the context of developing residential schools in the nineteenth century, and eventual forced conversions and Anglicized education in the latter nineteenth and twentieth.[3] One of the rare books analyzed was a prayer book with a section specific to Sunday school children:

This book from 1853 is a crucial piece of literature and evidence of the effective work the European missionaries— whose intentions were to steal land from the Indigenous peoples and bring them a Christian salvation — as they assimilated the Kanien’kehá:ka and worked to erode their cultural identity by converting them to Anglicized life. |

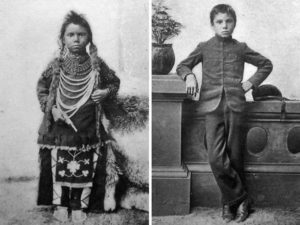

FIG 1: Thomas Moore, 1874 |

| Though residential schools are not a focus of these papers, these schools are important in that they were part of the same process of cultural erosion as the books found at Huron and Western. They reveal how British and Canadian officials used education to affect change in Indigenous language and literacy. Figure 1 visualizes these tactics. The picture is of Thomas Moore, a young Nehiyawak (Cree) boy who was taken from his family and put into a residential school in Saskatchewan. Notice how his dress and hair have been changed, providing a visual representation of how European missionaries stripped him of his Nehiyawak identity. The same thing happened to Kanien’kehá:ka children when they were taken and put into the Mohawk Institute in modern day Brantford. There was some discontent and apprehension among Indigenous elders and parents surrounding the expectation that Indigenous children attend missionary schools as the development of their language and objects of knowledge transfer could be altered with an Anglicized education. According to Elizabeth Elbourne, Haudenosaunee children resisted this practice by keeping their children nearby. “The more distant Indians” Elbourne writes, “being extremely averse to sending their Children abroad for Instruction… one might see Haudenosaunee people attempting to manage Christianity, keeping missionaries (and Haudenosaunee children) close at hand rather than sending their children away to missionary-run schools.”[5]

Fear of settler society was well-founded by the turn of the nineteenth century. Some Great Lakes Indigenous peoples even feared possible extermination by the government or the settlers it represented. Jeffrey Ostler writes that Indigenous peoples feared colonial malevolence. Though fearful, perhaps this is why they agreed to many terms and conditions missionaries and settlers laid out for them — things like treaties, sending children to residential schools, and altering their religion and way of life to live peacefully with the new people.[6]. As generations of Indigenous children were growing up, put into ‘schools’ and whitewashed, the native children lost their Indigenous identity. Through no fault of their own, they lost their language; in school it was forbidden, and if students went home for the summer, they were ashamed of their native culture and repressed it until they became pseudo-Anglicized European settler children. Crucial to both First Nations’ historiography and the longevity of their culture is a continuance of native Indigenous traditions, having a language, and a literate population of people. With the loss of language, colonial officers from Europe and interference in the upbringing of their children, Indigenous peoples were close to losing their cultural identity through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries[7]. However, there is evidence of a strength of character and resilience against evil, “Rather than simply existing as passive victims of a huge bureaucracy, students and parents found ways to push back as active agents.”[8] |

FIG. 2: Image from Claus Primer, 1786 |

| Figure 2 is an engraving of a late-eighteenth-century Kanien’kehá:ka. This photograph is especially important and significant as it points to the early period in which these people began to engage with colonial systems of schooling. Though structured much like colonial schools, what we see here is that they were educated and taught by elders from their own nation. In demonstrating their engagement with schooling, it is clear that the European missionaries who, in the later nineteenth century decided that all children must learn English, were incorrect in assuming that Kanien’kehá:ka children were uneducated and uncivilized. Education was embedded in their culture for years before the missionaries and white settlers arrived and wanted to change things.

European missionaries that traveled to Canada worked to conceive a ‘white Canada’, where they targeted Kanien’kehá:ka literacy as part of conversion tactics.

The evidence that this book from Western’s Rare Books Collection offers is that unlike this image, and many of the other books held in this collection, the Sunday School section appears solely in English. This demonstrates the ways in which missionary education was changing; children were not learning Kanien’kehá:ka language, but rather were being educated in a pseudo-European, entirely colonial system that was meant to radically change the Indigenous cultures. The historiography of the Kanien’kehá:ka people of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy in Canada, hand in hand with the historiography of Canada, is directly tied to the demonstration of eroded traditional-Indigenous culture presented in the ARCC rare book. Since the history of Canada is tied to the first peoples of Canada, and the Indigenous nations originated in Canada, their histories and succeeding historiographies are intertwined. The books in the Rare Book Collections connect these respective historiographies, as they demonstrate both the first peoples of Canada and the treatment they received, while showing the desire for colonial dominance within Canada. The passage from the ‘Hymns for Sabbath-Schools’ prayer book is a direct display of a forced loss of literacy among the new generation of Mohawk people. This book was published in 1884, and as such, it is clear that this cultural erosion was successful by the later nineteenth century. Methodist felt a particularly strong obligation with children in their commitment to make disciples of all and create a highly Christianized moral social order. Sunday schools, which were also employed by Thaddeus Osgood and missionaries representing other Christian denominations, were an important tool for Methodists in their attempts to morally transform and bind the children of setter and Indigenous populations to institutional religion.[10] Brendan Edwards discusses the missionaries and education directed towards children, although in a slightly different context, in his book Paper Talk. Though his focus is on Methodist ministers, the premise is identical. At the time of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Sunday schools were being developed by ministers and lay people alike who wanted to give a basic moral and educational foundation to poor people — including Indigenous peoples. The final but equally important literary aspect to the attempted erosion of Indigenous culture in Canada’s history is Indigenous-white treaty making. In The Royal Proclamation of 1763, there were clauses that constantly reassured Indigenous nations of the security of their lands and assured their safety[11]. In his book Compact, Contract, Covenant J.R. Miller describes this process:

Miller’s account of treaty-making in the region provides a vehement description of unjust Europeans and white practice in dealing with the Indigenous peoples. It seems as though the settlers, who, without Indigenous assistance would not have survived in Canada, went to extraordinary efforts to make deals with various nations. The colonialists from Europe clearly had ulterior motives in their connection with Indigenous peoples, sometimes attacking their weak fronts through coercion, bribes or even straight-up lies while using the mask of misunderstanding and illiteracy as a cover until deals were completed. Kristin Burnett provides another example of the problems with literary communication between Kanien’kehá:ka and European missionaries:

The land is a critical aspect in the study of literacies. It is an object of knowledge transfer and provides a type of language, to which we must be sensitive and attuned. The treaty problems as outlined above, coupled with nefarious schemes by white settlers, missionaries, or colonial figures sent to accumulate land – the physical space in which Kanien’kehá:ka lived and reestablish how life was to be lived – are evidence of the negative effect colonial intentions had on the first peoples of Canada. |

|

III: INDIGENOUS MISSIONARIES There were Indigenous peoples that grew up in settler villages, learned the English language and attended school either at a residential school or with settler children. As time developed, the missionaries got more comfortable with Indigenous people, and as generations of Indigenous peoples, specifically Kanien’kehá:ka, grew, colonial influences grew. They were born into mixed families, being baptized into various denomination of the Christian faith, learning the English language, and were going to school all under European guidelines and ideals. As early as the 1760s, the Mohawks had made many changes to their way of life. They had sold, given away, or been cheated of much of their land. They had adopted many European customs, such as drinking tea, and from Albany stores they bought English goods that ranged from women’s stockings to padlocks and knee buckles. They owned horses, sleighs, and wagons.[14] Some Indigenous peoples either truly followed Christianity or wanted to use it for personal gain, and decided to become a minister or preacher. When Indigenous peoples were leaders of the faith, they had a closer ties to more traditional Kanien’kehá:ka who did not believe in Christianity. As missionaries slowly became more and more successful in converting people, the Indigenous religious leaders were more successful in gaining a Christian following. They were trusted and easy to connect to by peoples of their same nation. There was more success with missionaries born from Kanien’kehá:ka nation as compared to strangers from Europe, as exemplified in Joseph Brant’s life story. His life and how it ties into this paper will be flushed out in the next section. Do not mistake, however, this argument as one suggesting that these people lost their culture and identity. In fact, on the whole I argue here that they were successful in not losing sight of Kanien’kehá:ka culture, language, objects of knowledge transfer, despite the best efforts of European missionaries that tried to assimilate them into the lifestyle of white people. These peoples, after a period where they did lose sight of their culture and identity, worked on teaching the native language to their children, rather than allowing the white residential schools to whitewash Indigeniety and the culture of being Kanien’kehá:ka out of them. |

|

IV: CASE STUDIES T’hayendenega (more commonly known as Joseph Brandt) was perhaps the best-known Kanien’kehá:ka of his time. His name is famous in the field of Indigenous studies, and within the historiography of Canada. His life story is the personification of the arguments presented in this paper. Directly tied to the Indigenous Missionaries section, T’hayendenega made an excellent connection to the attempted erosion of culture that this paper analyzes. He made great strides in creating relationships between English and Kanien’kehá:ka peoples and converting native Indigenous peoples to Anglicanism. T’hayendenega also worked to translate the Gospel of St. Mark into Kanien’kehá:ka language. His work in education and literacy was unparalleled at the time. The rare book examined throughout this paper, the book of Hymns[15] for people of ‘the Mohawk’ language is an example of the uses of language and literacies in this nation. T’hayendenega spearheaded alphabetic language development without eroding the importance of various objects of knowledge transfer within the community. Clearly T’hayendenega understood the importance of language, literacies, and other objects of knowledge transfer in Indigenous life, but some people may interpret that he used the importance of language and literacies to convert his peoples rather than reinforcing Kanien’kehá:ka history and culture. According to Lisa Brooks, in her analysis of Brant in The Common Pot, “Brant became convinced that the only sustainable route to the protection of Mohawk lands was a firm alliance with the Crown”[16]. T’hayendenega is not, however, primarily associated with religious missionary conversion, but rather in linguistics, as he was a language assistant to John Stuart in the early 1770s[17]. There was one point where T’hayendenega lost his faith in the British government — after diplomatic visits to Britain[18] — and was one of the key motivations for “his later political work trying to unite Indigenous peoples and make them independent of Britain”[19]. These significant distinctions allow one to see that although T’hayendenega was an Anglican missionary and tried to convert members of his nation to Christianity, everything he did in his life was to enhance the life of his people and to give them a fair chance in the world increasingly defined by colonial land grabs, lies in treaty making, confusion and trickery, and the fear of extermination.[20] T’hayendenega has another very strong tie to this paper, which is the connection to Kenwendeshon (Henry Aaron Hill). Kenwendeshon was the publisher of the Huron Rare Book that this paper is tied to, A Collection of Hymns for the use of Native Christians of the Mohawk Language, to which are added a number of Hymns for Sabbath-Schools. The key historical figure who embodies the argument that language and objects of knowledge transfer are the foundation of a culture, who are held together by the land they live on[21], is directly tied to the person that produced the book in which these arguments are anchored. According to Elizabeth Elbourne, Kenwendeshon was a member of the powerful Hill family. These men worked together to establish a better life for their people and communities, ensuring their land was not stolen and forging good relationships with Europeans and other missionaries. As they worked together and are written into the history of both Canada and the Kanien’kehá:ka nation, so are these men and their works connected to the present day through the Huron University College Rare Book Collection. |

|

V: KANIEN’KEHÁ:KA RESILIENCE As threaded throughout this paper, the main argument of an attempt at eroding Kanien’kehá:ka culture has been punctuated by the resilience of this culture which kept their individuality, language, literacy and land alive and intact right into present day. The resilience of the Indigenous peoples is the reason that historians today are able to study the existing historiography, rare books, objects of knowledge transfer, and other pieces of history and evidence left behind from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. As Indigenous children were sent to residential schools and became pseudo-Europeans, there were Indigenous peoples who ensured that their culture was never fully erased. Traditions, story telling, and the language continues to be passed down.

This passage from Makin perfectly summarizes how Indigenous peoples relationship with the land is central to daily life and everything in which one can possibly engage. As defined in the introduction, Indigeniety is the root word from which ‘Indigenous’ comes. It is a term anchored in the Land, which is central to daily life, to their history — and succeeding historiography of their nation — and to the future. Brooks has a strong understanding of land as a physical space in which Indigenous nations live in and amongst and how it shapes the past and present[23]. Indigenous nations fight for their rights, converse with the government, and ensure that their children are taught from a young age about their heritage. In schools today, Indigenous nations celebrate the success of their peoples, and preserve historical documents and buildings to ensure the historiography continues. |

|

VI: CONCLUSION Indigeniety and the unique cultural identity of the Kanien’kehá:ka nation was threatened in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. These people were faced with attempted cultural erosion, primarily at the hands of European missionaries and they worked on colonial land grabs and attacked native language and literacies. Some missionaries wanted to convert Indigenous peoples to deliver them from sin, but many had ulterior motives. The Rare Book Collections best demonstrates the struggles that Kanien’kehá:ka Indigeniety faced in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as they hold evidence of the arguments used to work against their culure — the material, the translator, and even the publisher. Chief Josiah Hill in a speech addressing the Six Nations Council said of schooling in 1902:

This passage is from Hill’s speech upon the opening of a school and serves as a segue into the concluding remarks that tie this paper together. As identified throughout, there are various ways that language, objects of knowledge transfer and education were used as a colonial tool by primarily European missionaries to assimilate and deprive the Indigenous peoples of Canada of their culture, lands and control. The Kanien’kehá:ka of Grand River selectively engaged with the white people, learned their foreign language and adopted new ways of life to live in harmony. But they were cheated. Huron and ARCC’s Rare Book Collections provide strong evidence of assimilation and a switch of basic language education, as demonstrated with the ‘Sunday Sabbath’ passages for Kanien’kehá:ka children was purely in English text. The various tools that European missionaries and colonial agents used to assimilate Kanien’kehá:ka peoples were in fact reversed and used to keep their unique and individual culture. This paper identifies and allows one to see the fast-paced history and historiography of Canada alter with time, and how the first peoples of this nation overcame adversity to be resilient in their beliefs, from the early presence of white settlers and missionaries to present day. [1] Francesca Merlan, “Indigeneity: Global and Local,” Current Anthropology 50, no. 3 (2009): 303, http://archanth.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/documents/merlan_capaper.pdf. [2] Matt Cohen and Jeffrey Glover, Colonial Mediascapes: Sensory Worlds of the Early Americas. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2014), 105. [3] Elizabeth Graham, The Mush Hole: Life at two Indian Residential Schools (Waterloo: Heffle Publishing, 1997), 2. [4] Henry Aaron Hill, A Collection of Hymns for the use of Native Christians of the Mohawk Language, to which are added a number of Hymns for Sabbath-Schools. (New York: American Tract Society, 1853), 147. [5] Elizabeth Elbourne, “Managing Alliance, Negotiating Christianity: Haudenosaunee Uses of Anglicanism in Northeastern North America, 1760s-1830s,” in Mixed Blessings, eds. Tolly Bradford and Chelsea Horton (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2001), 41. [6] Jeffery Ostler, “‘To Extripate the Indians’: An Indigenous Consciousness of Genocide in the Ohio Valley and Lower Great Lakes, 1750s-1810,” William and Mary Quarterly 72, no. 4 (October 2015): 587. [7] Graham, 39. [8] Kristin Burnett and Geoff Read, Aboriginal History: A Reader (Ontario: Oxford University Press, 2012), 213. [9] Hill, A Collection of Hymns, 147. [10] Brendan Frederick R. Edwards, Paper Talk: A History of Libraries, Print Culture, and Aboriginal Peoples in Canada before 1960 (Maryland: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2005), 47. [11] J.R. Miller, Compact, Contract, Covenant: Aboriginal Treaty-Making in Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009), 7. [12]Ibid. [13] Burnett, 386. [14] Jennifer E. Monaghen, Learning to Read and Write in Colonial America (Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2005), 185. [15] Hill, A Collection of Hymns, 12. [16] Lisa Brooks, The Common Pot: The Recovery of Native Space in the Northeast (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2008), 115. [17] Elbourne, Mixed Blessings, 53. [18] Ibid., 54. [19] Ibid. [20] Ostler, To Extripate the Indians, 587. [21] Brooks, The Common Pot, 254. [22] Laurie Makin, Criss Jones Díaz and Claire McLachlan, eds. Literacies in Childhood: Changing Views, Challenging Practice (Australia: Elsevier Australia, 2007), 232. [23] Brooks, The Common Pot, 252. [24] Keith Jamieson, History of Six Nations Education (Brantford: The Woodland Indian Cultural Education Centre, 1987), 19. |

| Bibliography |

|

Bradford, Tolly and Chelsea Horton, eds. Mixed Blessings: Indigenous Encounters with Christianity in Canada. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2001. Brandão, J.A. and William A. Starna. “The Treaties of 1701: A Triumph of Iroquois Diplomacy.” Ethnohistory 43, no. 2 (1996) 209-244. Brooks, Lisa. The Common Pot: The Recovery of Native Space in the Northeast. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2008. Burnett, Kristin and Geoff Read. Aboriginal History: A Reader. Ontario: Oxford University Press, 2012. Cohen, Matt and Jeffrey Glover. Colonial Mediascapes: Sensory Worlds of the Early Americas. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2014. Calloway, Colin G. The Indian History of an American Institution: Native Americans and Dartmouth. New Hampshire: Dartmouth College Press, 2010. Edwards, Brendan Frederick R. Paper Talk: A History of Libraries, Print Culture, and Aboriginal Peoples in Canada before 1960. Maryland: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2005. Graham, Elizabeth. The Mush Hole: Life at two Indian Residential Schools. Waterloo: Heffle Publishing, 1997. Hill, Henry Aaron. A Collection of Hymns for the use of Native Christians of the Mohawk Language, to which are added a number of Hymns for Sabbath-Schools. New York: American Tract Society, 1853. Jamieson, Keith. History of Six Nations Education. Brantford: The Woodland Indian Cultural Education Centre, 1987. Makin, Laurie, Criss Jones Díaz and Claire McLachlan, eds. Literacies in Childhood: Changing Views, Challenging Practice. Australia: Elsevier Australia, 2007. Merlan, Francesca. “Indigeneity: Global and Local,” Current Anthropology 50, no. 3 (2009): 303-33. http://archanth.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/documents/merlan_capaper.pdf. Miller, J.R. Compact, Contract, Covenant: Aboriginal Treaty-Making in Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009. Monaghan, Jennifer E. Learning to Read and Write in Colonial America. Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2005. Ostler, Jeffery. “‘To Extripate the Indians’: An Indigenous Consciousness of Genocide in the Ohio Valley and Lower Great Lakes, 1750s-1810,” William and Mary Quarterly 72, no. 4 (October 2015): 587-622. Smith, Donald B. Sacred Feathers: The Reverend Peter Jones (Kahkewaquonaby) and the Mississauga Indians. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2013. Stevenson, Angus and Christine A. Lindberg, eds. New Oxford American Dictionary, Third Edition. Cambridge: Oxford University Press, 2010. |