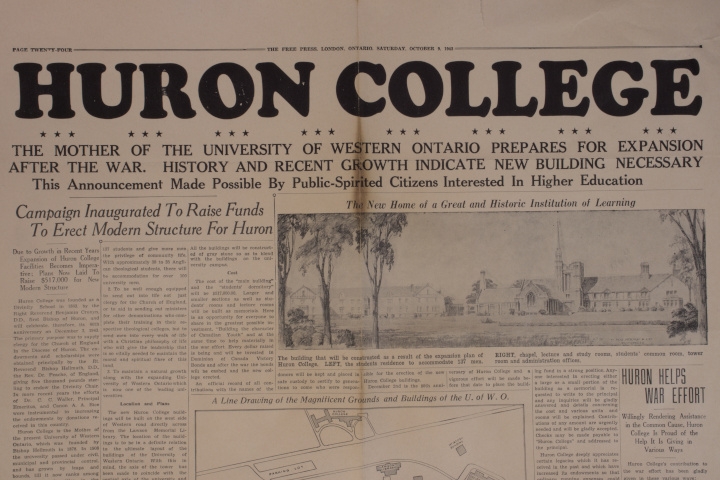

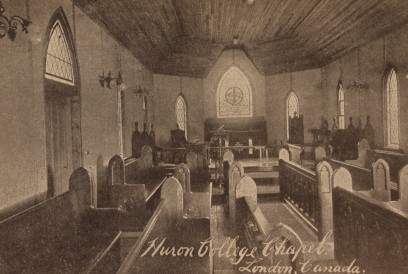

When Huron was a creaky, much-expanded former estate home, his father, John M. Moore, created plans for a new campus. He had a list of things to follow. The college was a mix of residence and teaching. They were a large family, a brotherhood of like-minded and passionately Christian people. The old Huron building evolved from an Italianate home—symmetry, wide cornices, pediments, and pilasters—into an ad hoc monster, a dizzying assortment of additions over 30 years. So, John Moore designed a campus that was laid out like a home—two wings of dorm rooms connecting to a central hallway and a common room in the middle.

His plans were rejected.

The glorious symmetry and strength radiating from the proposed banks of windows and thickly buttressed stone tower were too much for the Huron Executive Council. This was in 1934 and the heart of the Depression. I like to think that John Moore threw up his hands in disbelief, that the rejection was incomprehensible.

John’s son, O. Roy Moore, however, did have a pretty good idea of what Huron wanted. Maybe he tried to convince his dad, a classic case of exuberant youth arguing for innovation in the face of the parent being steadfast to tradition. It was his name on the new drawings of a quaint and asymmetrical building that was accepted as the design for the new Huron College. Where the first design was rigid and bold, the new had a sense of tranquility and unfolding in a meandering way.

Huron College 1863-1965, AFC 338-S1-SS8-F8, Western Archives, Western University.

The Idea to Move

The current Huron campus and the move to relocate find their beginnings with the Moore & Architects architectural firm. In 1932, after having purchased the property on Western Road, The Huron College Executive Council approached John M. Moore to draft plans for a new Huron campus building (Moore 1933). The three versions that John M. Moore drafted were symmetrical, bold, and slightly imposing. The square tower above the main doors had massively thick buttressed walls, and rows of identical rectangular windows were equally spaced apart and aligned. Two wings extended from the main doors, symmetrical from the front façade view. All rooms—bedrooms and classrooms—were sensibly connected to a central hallway. Both wings met in the middle, by the entrance, where there was a common room, chapel, and library from the second floor to the basement, respectively. The design felt gothic, with intricate and carved stone cornices and window frames, but with classical symmetry. The proposed campus was too grand, or bold, because new plans were drafted the following year.

Oliver Roy Moore, the son of John M. Moore, drafted a new series of plans (Moore 1934). These roughly resembled the portion of the current Huron Campus that connects the great hall and chapel with the O’Neil residence and the original dining hall. These plans were less bold and imposing—somewhere between a Victorian cottage and a gothic stone Anglican church. The building was asymmetrical, featuring wood decoration mixed with stone and brick, and slightly more subdued gothic stone decoration. Some elements carried over from the previous iteration; Huron College’s Executive Committee evidently liked some aspects of the first designs.

The new designs were less imposing and symmetrical, but they kept a similar core concept of how the space was to be used. Both plans detail a campus that has a strong residential feel, with residences for students, the principal, and the bishop. The continuity between these drawings indicates that Huron College would keep the atmosphere of a tight-knit family of theological students. Switching from John M. Moore to his son O. Roy Moore drafting the drawings is most likely the architectural firm’s decision, rather than starting from scratch with a new architect. The clear continuity from the old to the new drawings points toward John M. Moore easing his son into his firm where many of the conceptual decisions had already been made. It is unclear how much John M. Moore influenced the drawings bearing his son’s name.

Moore listened as O’Neil and the others explain the fundraising plans. The money for the college would come almost entirely from the Church and nearby parishes. He held the brochure in his hand, looking over the neat breakdown of “the plan”: all Anglican families in the Diocese of Huron should average a $10 donation. He glanced over the “why column” on the right side, reading:

New Huron College buildings are urgently needed. The present college rooms are inadequate and overcrowded. Huron college must keep pace with the rapid growth of the University of Western Ontario as a whole. The completed college will stand as a triumphant achievement of the people of the Church and friends of this institution throughout this area—an achievement which should not belong alone to the immediate college family or to the men who initiated the project but to the people at large, throughout the entire area.

Extensive Fundraising

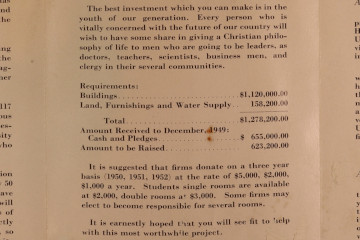

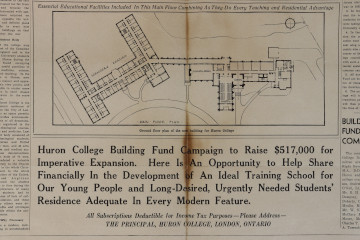

O’Neil and the Huron Executive Council led a fundraising campaign periodically throughout the 1930s and 1940s. They planned to fundraise from Anglican dioceses of Southern Ontario with a focus on London, Hamilton, and Toronto. The fundraising committee meeting minutes list New York as a potential fundraising location for Anglican dioceses. The executive committee appealed to the Rockefeller foundation with a detailed proposal of the building and a call for funds (“Building Fund Committee 1942”). No response to that appeal is mentioned in the meeting minutes. The executive committee planned to approach banks for additional funds if fundraising was not enough. It is not clear how much was eventually fundraised and how much was from bank loans. However, after relocation, the Executive Committee began another fundraising campaign to “free [the] college of debt” (“The New Huron College” brochure from 1951). Presumably, this debt was from loans to build the campus. These loans supplemented the substantial—but unexpectedly outmatched—donations.

Both diocesan donations and bank loans were needed to cover the increased construction cost after the wartime increase in demand for steel. From skyrocketed wartime demand for steel, the cost had doubled by the time Huron’s executive committee began construction. This increased the cost of relocation from $617,000 in 1945 to $1,353,000 in 1951 (“Building Fund, 1953). This increase deeply complicated fundraising that was almost entirely met already from diocese donations. In 1949, the executive committee initiated a new fundraising campaign. This campaign had a sense of urgency: the contract had already been signed with the Pigott Construction Company on May 11th, 1949 for $1,120,000 to build O. Roy Moore’s designs (“Executive Board – Planning and Property Builders Agreement”, 1949). The fundraising brochures were only sent out on June 14th (“Building Fund Committee”). The relocation transformed from a dreamy sketch on a fundraising brochure and discussion item at meetings to a physical, permanent building.

Educational Trends and University Expansion

The following is an adapted version of a literature review I wrote titled: “A Review of Architectural Design and Educational Aspirations in University Expansions“. The full review is accessible via the button below, or from the menu at the top of the page.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the university institution was at a turning point in its educational aspirations and architectural design. Dramatic increases in technology, global governance, and population following World War II led to a greater need for post-secondary education in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields. The importance of these fields in the Cold War arms race coincided with new styles of university architecture. With geometric concrete and glass shapes and a lack of embellishments, the new brutalist and modern constructions were starkly different from traditionally neo-gothic University buildings.

STEM studies became associated with the new architecture. However, just because STEM fields and brutalist university architecture were correlated in the postwar period, one did not necessarily cause the other (Campbell 2011). New buildings at British universities such as Oxford were in the brutalist style due to a lack of funds for extravagant materials or designs. More often than as a deliberate prioritization of STEM studies, brutalist architecture was chosen for its affordability and rapid construction: brutalist architecture minimized a university’s costs (Campbell 2011, 396). Without intricate or laborious details, large-scale University expansions were much more financially feasible in the brutalist or modernist styles using predominantly concrete, steel, and glass.

Unlike most university expansions in 1960, Huron’s campus construction was styled after older, more traditional Tudor and Edwardian styles. This was for a variety of reasons, such as:

- The campus designs were created when that style was contemporary, in the 1930s, and only delayed until 1950 due to gradual fundraising and a material shortage;

- Modernist university constructions tended to be expansions on existing neo-gothic or neoclassical architecture, supplementing rather than defining an entire campus;

- The architecture and layout invoke a strongly religious (theological) atmosphere, and not coincidentally Huron was definitively an Anglican theological institution for training priests for the Anglican ministry.

It is easy to assume that the architectural style of the new Huron campus was dated because it was not visually similar to postwar modernist and brutalist styles. In a sense, this seems to be true in the sense of nostalgia or regret that Huron College did not have a storied neo-gothic campus like most 20th-century universities. Or perhaps so the campus would be reminiscent of Anglican churches and give a Christian atmosphere to the construction—walking through the cloister-styled arches, or the ribbed-vault-hallway outside the great hall, this effect has certainly been achieved. These motivations do not necessarily clash with the brutalist trends in the sense that makes Huron seem outdated. Rather, it is crucial to remember that brutalist constructions on campuses in Southern Ontario—Guelph, Western, Toronto, Waterloo, Hamilton, and others—accompany existing neo-gothic buildings from the late 19th or early 20th century. It is far less common for entire academic institutions with origins in the 19th century—such as Huron College—to relocate to a completely modern or brutalist campus and scrap the old one.

Bibliography

Appleyard, R. T. (1937). The origins of Huron College in relation to the religious questions of the period. 1937. University of Western Ontario, MA thesis.

Campbell, Louise. “Building on the Backs: Basil Spence, Queens’ College Cambridge and University Architecture at Mid-Century.” Architectural History, vol. 54, Cambridge University Press, 2011, pp. 383–405, doi:10.1017/S0066622X0000410X.

Coulson, Jonathan, et al. University Trends: Contemporary Campus Design. 2nd ed., Routledge, 2018, doi:10.4324/9781315213606.

Fagerlid Cicilie, et al. “Engaging with Mixed-Use Design”. Architectural Anthropology, London: Routledge, 2021, pp. 121-133. https://doi-org.proxy1.lib.uwo.ca/10.4324/9781003094142

Gowans, Alan. “Twentieth-Century Canadian Architecture as Cultural Expression.” Journal of Canadian Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, Trent University, 1966, pp. 24–35, doi:10.3138/jcs.1.1.24.

Hancock, Philip. “Academic Architecture and the Constitution of the New Model Worker,” (Mar 2011), https://doi.org/10.1080/14759551.2011.544885

Holleran, Max. “Concrete Monsters of the Welfare State: Discussions of Brutalist Architecture on Social Media.” Space and Culture, 2021, p. 120633122110193–, doi:10.1177/12063312211019384.

Owram, Doug. “5. School Days, 1952-1965”. Born at the Right Time: A History of the Baby Boom Generation, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018, pp. 111-135. https://doi-org.proxy1.lib.uwo.ca/10.3138/9781442657106-006

Talman, James John. Huron College, 1863-1963. Huron College, 1963.

Thomas, Christopher. “‘Canadian Castles’?: The Question of National Styles in Architecture Revisited.” Journal of Canadian Studies, vol. 32, no. 1, University of Toronto Press, 1997, pp. 5–27, doi:10.3138/jcs.32.1.5.

Tromly, Benjamin. “The university in the Soviet social imagination”. Making the Soviet Intelligentsia: Universities and Intellectual Life Under Stalin and Khrushchev, Cambridge University Press, 2013, pp. 53-76. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139381239.