Huron College 1863-1965, AFC 338-S1-SS8-F8, Western Archives, Western University.

Aerial Views of Campus, AFC 339-S2-SS1-F1, Western Archives, Western University.

November 9th, 1951 must have been an exciting day; the new Huron College was officially opened. The headline from the London Free Press, as I zoom in on the microfilm reader, reads “Archbishop Opens Huron College.” On the right side of the accompanying picture is O’Neil, looking incredibly young beside much older clergymen.

O’Neil resigned from the office of principal a year after the new College was opened. It is strange to imagine working tirelessly for a decade to accomplish something and then not staying to enjoy it when it is accomplished. Was Huron’s relocation just the first step in launching his career? He went on to be General Secretary of the British and Foreign Bible Society, where he most likely had a greater reach to spread his religion. Was that how he thought of Huron’s relocation, necessary for Huron College so that it could better provide more youth with religious education? Was it just a stepping stone on a career path to what he perceived as bigger and greater things?

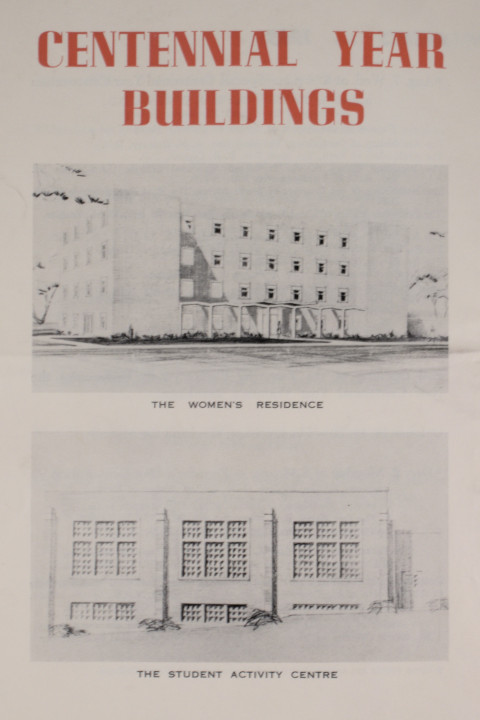

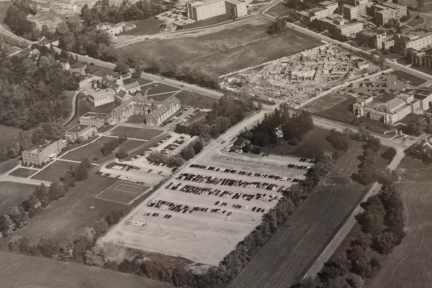

In the years after O’Neil left, the new campus underwent radical change. For O’Neil, the relocation was the conclusion of decade-long efforts. For W.D. Coleman, it was the beginning of a refreshed Huron College. Hellmuth Hall was built in 1957 and the first women enrolled at the College started to live in residence. The Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences was created; arts courses went from being fledgling electives to full-blown degree programs. More students meant the campus was more cramped, so a new library and reading room were built in 1958 to hold 100,000 books. The same year, the Huron Executive Council became the Huron Corporation, when the Lay Representatives—such as O. Roy Moore—officially were no longer apart of the Huron Executive Council.

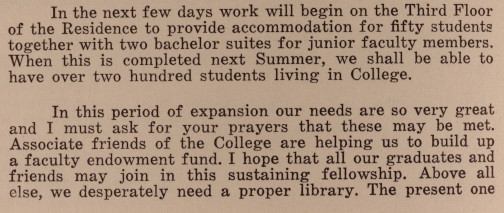

There was no mention in 1949 or 1951 that Huron College would have women enrolled and in residence in less than a decade. Nor was there a plan to build the library and reading room in 1958. The only construction anticipated in 1951 was renovations on the third floor of the O’Neil residence for a handful of student bedrooms.

O’Neil and Moore [Exeunt]

What did O’Neil and the executive committee plan for after relocation? Was building a completely new campus on a new site purely a practical matter of needing more space? Did the Executive Committee foresee any evolution of the College beyond being a small theological college? The College was officially opened for full-time students and classes in the fall of 1952, with no further construction anticipated or planned except for completing partly-finished third-floor residence rooms (O’Neil, “Report to the Corporation”, 1950). Accomplishing the monumental feat of fundraising $616,000 in donations, overcoming an unanticipated doubling in costs, and staying dedicated to a relocation plan for almost twenty years are all impressive achievements. While O’Neil and the Executive Committee could plausibly have felt satisfied with what they had accomplished, it is strange to think that the passion for and dedication to Huron College—enough to work tirelessly for a completely new campus— would dissipate so quickly. Huron College was a very tight-knit community; there was simply no space or too high a population before not to be familiar with other students and faculty, and both interviewees attest to Huron’s community as “one big happy family” (Appleyard, pp. 5). If O’Neil was proud and emotionally attached to the college, would he not stay to enjoy the brand-new campus, which he saw as a necessary improvement?

Spearheading a complete campus reconstruction, O’ Neil was ambitious. He had plenty of experience and respect with the Executive Committee to remain Huron College’s principal for the foreseeable future. Instead, he resigned to become General Secretary of the British and Foreign Bible Society (Talman 1963). He was replaced by W. D. Coleman.

W. D. Coleman Arrives

While O’Neil may have seen the relocation as the end goal for the College, W. D. Coleman saw it as the beginning. The larger capacity for students, along with more teaching spaces and land to expand on in the future, would be essential to reinvigorate the College within the community

…through the provision and encouragement of strong church-related colleges within the framework of our great universities. Such colleges should exist to create through a residential student community a Christian ethos and to foster humane studies in which the Christian perspective and Christian values are exposed with intelligence and without apology.” (Coleman, “Report to the Corporation”, April 25, 1958).

O’Neil had advocated for a similar purpose on the fundraising brochures. Yet W. D. Coleman differs from O’Neil’s view: a liberal arts college should “challenge its students by confronting them with the Christian outlook so that if they espouse it, they may do so intelligently; if they reject it, they may do so for important and not trivial reasons” (Coleman “Report to the Corporation”, April 25, 1958). W. D. Coleman gave this speech in the great hall in 1958 after the Silcox Memorial library was completed (Coleman, “Report to the Corporation”, April 25, 1958). This library was the latest in a series of new expansions to the Huron campus since W. D. Coleman became principal in 1952.

None of the additions completed under W. D. Coleman were planned for or anticipated by those who orchestrated the relocation, apart from the third-floor residence renovations. All of the changes brought to Huron College were encouraged by W.D. Coleman’s administration. The Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences (FASS) was created in response to increasing enrolment in arts and social science courses as electives by Western or Huron’s theological students. FASS immediately surpassed theological programs in enrolment. Hellmuth Hall, the first women’s residence, was completed in 1956. The new library was built to accommodate the increased student population. In 1958, the Executive Committee was abolished and replaced by the Huron Executive Corporation. Many of the representatives to the various committees that governed all aspects of Huron College were disbanded, including O. Roy Moore as Lay Representative.

Huron College would now be governed by a central corporate body and a board of directors. This change symbolizes the transition from the familial theological Huron College to a fully-fledged—but focused—liberal arts college. Huron College was still a heavily theological and Christian school—in its traditions, architecture, chapel, and motto of “true religion and sound learning” (Coleman, “Report to the Corporation”, April 25, 1958). Yet, relocating the campus gave Huron College an opportunity to reevaluate its role in educating the postwar generation. Huron College’s motivations to expand as part of the larger global trends in post-secondary education were centered around increasing enrollment while maintaining Huron’s focused role in providing a liberal arts education with a Christian perspective.

Throughout this project, it has been interesting to develop a better understanding of the processes in which Huron College adapted to contemporary needs during a time of global change in Universities while maintaining its tradition and purpose. It has been interesting and strikingly relatable how students and faculty experienced and adapted to the evolving Huron College of the 1950s as a community.

Moore listened as O’Neil and the others explain the fundraising plans. The money for the college would come almost entirely from the Church and nearby parishes. He held the brochure in his hand, looking over the neat breakdown of “the plan”: all Anglican families in the Diocese of Huron should average a $10 donation. He glanced over the “why column” on the right side, reading:

New Huron College buildings are urgently needed. The present college rooms are inadequate and overcrowded. Huron college must keep pace with the rapid growth of the University of Western Ontario as a whole. The completed college will stand as a triumphant achievement of the people of the Church and friends of this institution throughout this area—an achievement which should not belong alone to the immediate college family or to the men who initiated the project but to the people at large, throughout the entire area.