The 1852 Toronto edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Local Provenance, and the Case for Copies.[1]

First serialized in The National Era, in June of 1851, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin was published in book form in March of 1852 by the Boston firm of John B. Jewett and Co. A powerful, critical assessment of American slavery, Stowe’s novel joined a long line of slave narratives in print. In fact, Stowe had modelled many of the scenes in Uncle Tom’s Cabin on previously published narratives produced by writers such as Frederick Douglass and Josiah Henson.[2] While Stowe may have looked to an established, familiar genre for her story, the popularity of her work was unprecedented. The book’s first printing of 5000 copies sold out within weeks. Subsequent printings would follow throughout the year and the demand was so great that Jewett had to outsource work to multiple presses, papermakers, and binders. By October of 1852 the book would see more than 120,000 copies produced and by the Spring of 1853 the novel reached a staggering 310,000 copies sold. Western’s copy of Jewett’s first edition is from one of these later printings. The tag “One hundred fifteen thousand” found on the copy’s first title page, in Image 2 below, provides evidence for this more precise dating.[3]

[1] This post was inspired by the Phantoms of the Past Project. https://www.huronresearch.ca/phantomsofthepast/

[2] Stowe would point to some of these influences in her The Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin: presenting the original facts and documents upon which the story is founded (Boston, Jewett, 1853). The use of Josiah Henson’s story, in particular, did not escape Henson and the connection between his story and Stowe’s novel was used to market later editions of his narrative. Henson’s edition first appeared in 1849 and was later expanded over the next three decades. Image 1 shows the title page and image of Henson from Western’s copy of the London Ontario 1881 edition.

[3] My discussion of the printing and publishing of the various editions of Uncle Tom’s Cabin is based on the thorough discussion in Michael Winship, “Uncle Tom’s Cabin: History of the Book in the United States” http://utc.iath.virginia.edu/interpret/exhibits/winship/winship.html

The early Canadian editions of the work, which have received far less scholarly attention, carry similar clues to the work’s print history. In his preface to the second Toronto edition, Thomas Maclear could write that “The rapid sale of the first Canadian re-print of Uncle Tom’s Cabin has rendered it necessary to offer it to the public, in three weeks from the issue of the first” (Image 3) (Preface, iv). Exactly when the first and second Canadian editions appeared in bookstores is difficult to confirm, but a possible clue exists in another Maclear publication. Maclear had arrived from Ireland to Canada West in the late 1840s and was selling, printing and publishing books by the early 1850s.[4] In 1852, he would launch The Anglo-American Magazine (Image 4), a serial designed to compete with British and American periodicals. In the second issue of August 1852, in a section entitled “The Editor’s Shanty,” a dialogue unfolds between various characters, including one named Maclear. At one point in the exchange, Maclear is asked: “what roll of paper is that which you carry like a Field Marshall’s baton?” to which Maclear replies, “they are some proof-sheets of the re-print of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Life Among the Lonely,” I am bringing out, and which, please the fates and the printers, will appear before the world is much older!”[5] While this exchange does not provide us with firm evidence of a date for the early Toronto editions, that it appears in an August issue suggests a Fall-Winter 1852 printing as likely. This in turn may explain the discrepancy between the title-page and the upper board of Western’s copy one. The first has a date of 1852 while the board reads 1853 (See images 5 and 6). Similar to the First American edition mentioned above, the Canadian copy has the tag “Eight thousand in Canada” on the upper board. One possibility is that new boards were produced in 1853 for unsold stock of the late 1852 printing. While I will speak about copy-specifics in more detail below, it is worth pausing on the importance of this material feature. The board not only gives us a sense of the number of copies sold and the possible timing of the issue, but also clues to the price. Although partially blotted, it seems to read 3 shillings 2 pence.[6]

Elizabeth Hulse, “MACLEAR, THOMAS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 17, 2019, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/maclear_thomas_12E.html.

[5] The Anglo-American Magazine. Vol. 1 – Toronto, August, 1852. – No.2 p.174

[6] The thought that Maclear might reprint a board with a new imprint date follows a longstanding practice. In the case of Maclear, this alteration is also supported by his work on other publications. As Patricia Stone has shown in a detailed survey of one of Maclear’s earliest works, copies of Maclear’s first book survives in variant states, with plates and maps added, removed or rearranged. See “The publishing history of W. H. Smith’s Canada: past, present and future: A Preliminary Investigation,” Papers of the Bibliographical Society of Canada, 19 (1980): 38–68.

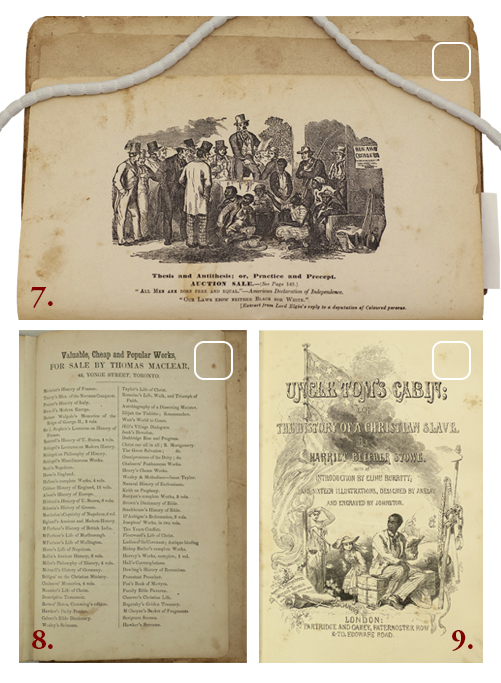

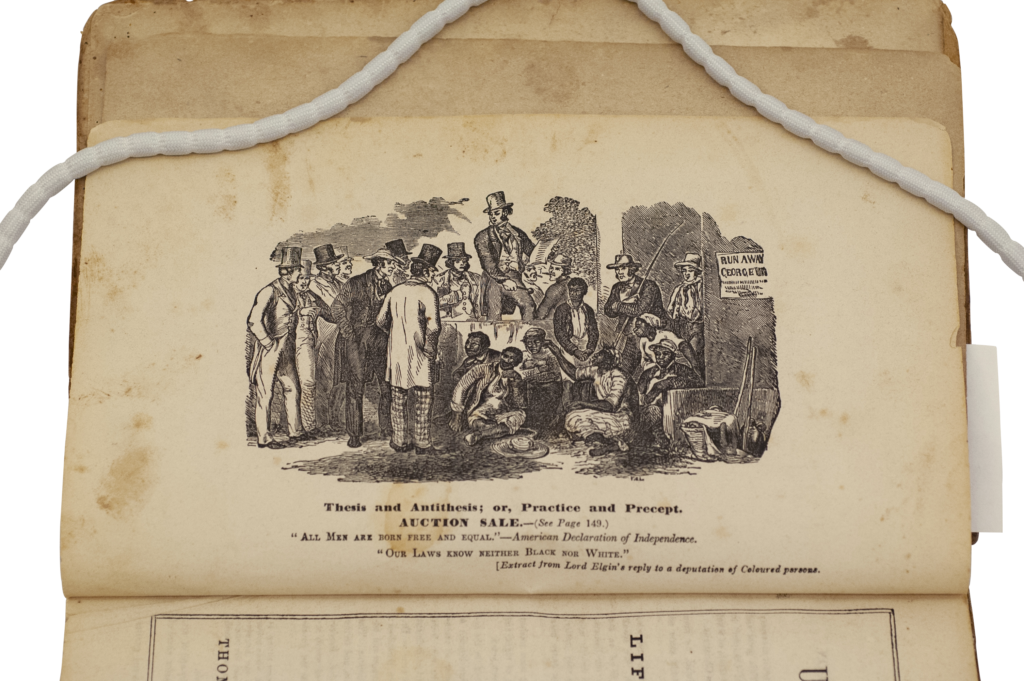

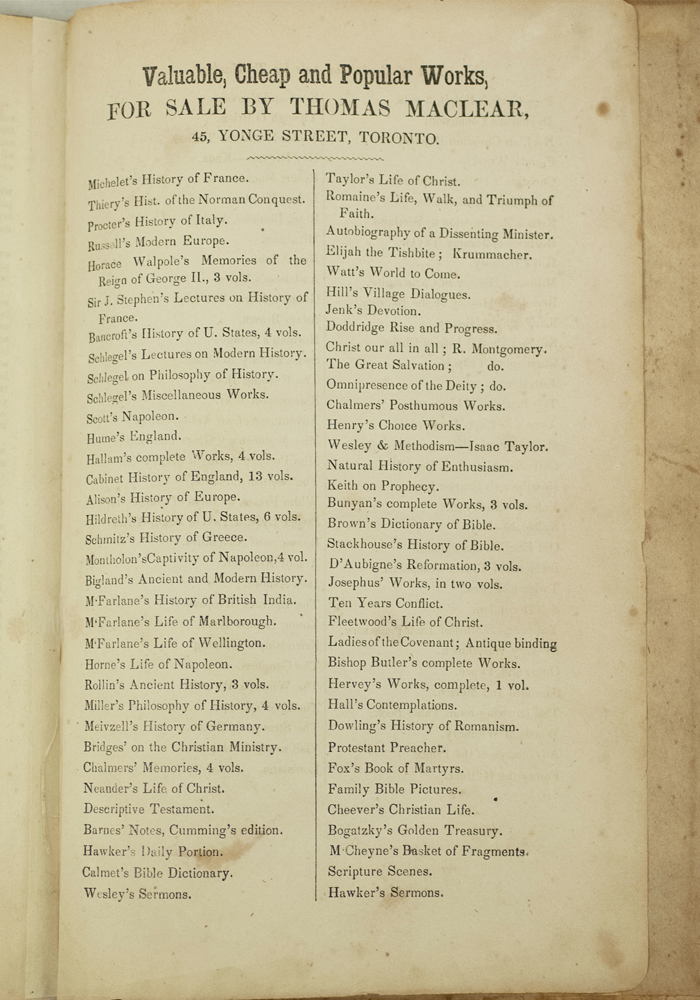

While Maclear’s edition might have been marketed as a re-print, it is not a simple reproduction. For one thing, the text is printed in double-columns, a decision that would have required less paper and thus reduced overall costs.[7] The Toronto edition is also reassembled. The illustration of “The Auction sale” found in the first American edition is placed mid-text, near the episode, whereas in the Toronto edition it is found at the start of the volume and retitled (Image 7). The original Stowe preface has also been removed and replaced in the Toronto edition by a preface from the publisher. Finally, at the end of the Toronto edition is a list of Thomas MacLear’s larger stock of books (Image 8), and on the back board, a more targeted advertisement. While such textual changes may seem secondary, the addition, removal, or rearrangement of these paratexts matters as it alters the reading experience. In fact, a quick glance at this early British edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, published by Partridge and Oakey, offers yet another example (Image 9). In this heavily illustrated edition, with a new preface by Elihu Burhitt, readers are invited to view with sixteen separate illustrations. In fact, this study of image begins with the title page. Studying Maclear’s edition and others produced that year reminds us of the complex, and in some cases, neglected textual history of this most famous of novels.

Local Provenance

One of the things that makes the books at Western and Huron unique is their local provenance. Indeed, many copies found throughout the Special Collections, the Open Stacks, and Storage can be traced to owners in Southern Ontario, both those affiliated with Western and Huron (e.g. Past Principals, Deans, Bishops, and Students) and those who maintained private collections in the region. That we still have these books is remarkable. Indeed, we owe a great debt to the librarians and archivists of the last century and a half for helping to ensure that these unique copies were preserved. The goal now is to study these books carefully, catalogue the unique features in copies to accord with RBMS standards, and better publicize the research potential of particular collections. As I reflect on the books just discussed, I will do so with an eye to their local value.

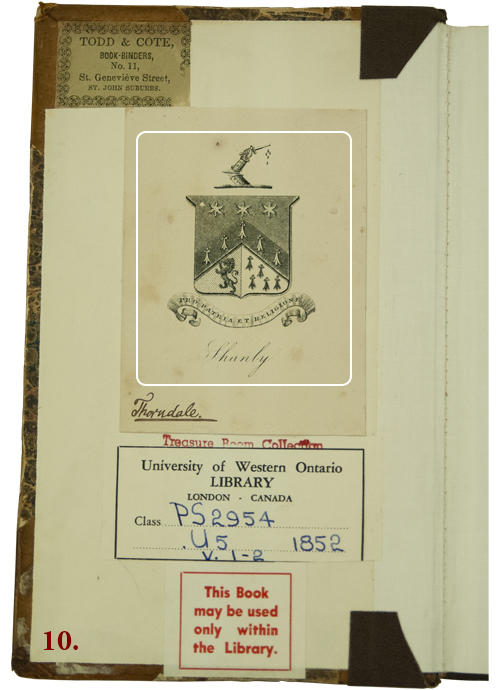

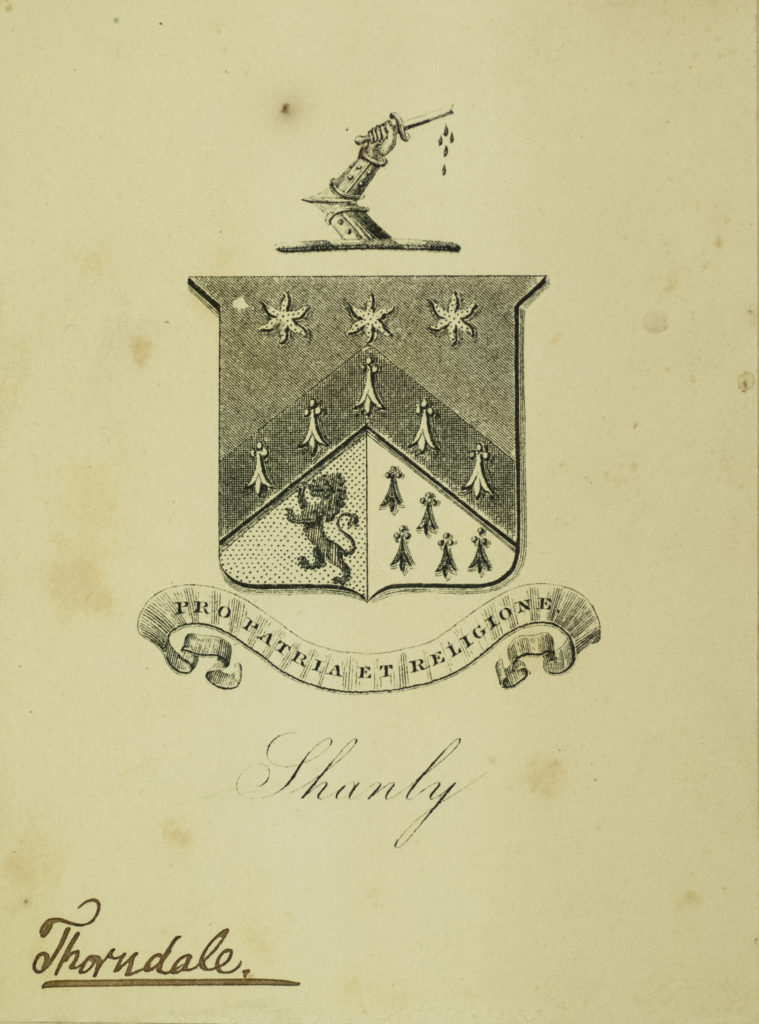

1. I opened the post with a brief discussion of Western’s first edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, published in Boston, by Jewett, in 1852. I started with it to emphasize the popularity of the work, the enormity of the print run, and the likely date of Western’s copy. What I ignored was its post-print history. For example, although the work was issued in two volumes, Western’s copy is rebound as a single book in half marble over calf boards. We also have a clue to where the book was bound, for on the inner pastedown is the Quebec City bookbinder’s ticket of Todd and Cote. It also contains the armorial bookplate of James Shanly who immigrated to Canada from Ireland in 1836 and moved just outside of London, Ontario. He would name his house Thorndale and the village located 30 minutes from London Ontario would carry the name thereafter (Image 10). Archivists at Western have located some 59 books with the Shanly ex libris and I discovered two additional Shanly books in storage earlier this year. I am convinced there are more books with this important local provenance waiting to be discovered in the stacks and storage. It’s worth noting that the Shanlys, along with the Harris’s, who arrived in London Ontario in 1834, are among the earliest local families in the area of which we have significant archival remains. What might these examples from their libraries teach us about book collecting at its inception in southwestern Ontario? How might the study of Shanly books in conjunction with the related archival materials help us to recover the larger social and intellectual pursuits of this early settler family? Did the Shanlys collect other books related to abolition and anti-slavery and how did their collecting fit with other documented examples from the period? These are just a few lines of research that might be pursued.

2. Next in the post came my discussion of the two copies of the Canadian edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. There too I focused on aspects of printing and illustration with some attention given to binding. What I left undiscussed was provenance. The first copy has no specific evidence of a previous private owner, although the faded stamp of “Released by U of M Libraries” may be a reference to University of Michigan. The second copy, although rebound and thus less interesting in one sense (Image 11), is more interesting in terms of its ownership. On the inner pastedown is the bookplate of J.D. Barnett and on the first endpaper is the name of John Davis Barnett with date “1917” and accession number “#41957.”(Image 13) 2018 saw the centenary anniversary of Barnett’s famous donation to Western. In 1918, Barnett, an English immigrant and Engineer for the Grand Trunk Railway, donated his collection of c. 40,000 books to the University at a time when Western had less than 5,000 imprints. The Barnett library, which had been previously housed in Stratford Ontario, included a wide array of subjects, ranging from examples of early incunabula, famous works in the history of science, a rich collection of both American and Canadian literature, and what was possibly the largest collection of Shakespeare in Canada at the time. While it might be easy to see this second copy of the second Canadian edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin as redundant, we might think otherwise when we consider it within the larger collection of abolition and anti-slavery material that Barnett collected. Similar to the discussion of Shanly above, the Barnett collection offers another window into the collecting habits (this one on an even larger scale) of a local collector and key evidence for understanding Western’s earliest collections. To study Barnett and his books is exciting research, but to preserve and carefully catalogue the books from his library is a matter of heritage, an ethical responsibility.

3. And now to The Anglo-American Magazine. Here I spoke about Maclear and the short interlude over proof sheets for the Canadian edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. What about its provenance? Of the five-volume set, one of the copies was owned by Barnett, but the other volumes were owned by Matthew Teefy (1822-1911), an Irishman who immigrated to York (later Toronto) in the 1820s, before moving to Richmond Hill where he served as postmaster-General for 61 years (Image 14). Is it a stretch to suggest that a postmaster-General would be interested in a magazine that focused heavily on civic activities across Canada West (later Ontario)? Archival fonds for Teefy survive at Queen’s Park and some of his books are found at The University of Toronto’s Thomas Fisher Rare Library.

While one could find all of the books just mentioned digitized online, and so seemingly made accessible to all, what you won’t find are the Western copies, copies which offer clues to early Canadian collecting, copies that take us back to the foundations of a University’s origins, copies that carry unique local provenance. While this post may focus closely on the particulars of a few books, what’s at stake is much larger. To study imprints at places like Western (founded 1878) and Huron (founded 1863) is to encounter more than a store of dusty old books, but books with rich local histories waiting to be uncovered. The books might be old, but the research on these local collections is, in many ways, just starting.

Bibliographical Details:

Stowe, Harriet Beecher. Uncle Tom’s Cabin or Life Among the Lowly. Boston: John P. Jewett and Co.; Cleveland, Ohio: Jewett, Proctor and Worthington, 1852.

Printed by George C. Rand and Co. No. 3 Cornhill.

Stereotyped by Hobart and Robbins. Boston

“One hundred fifteen thousand” on title page to volume one

and

“One hundred ten thousand” on title page to volume two.

Two volumes bound as one in half marble over calf boards. Spine rebacked with later label.

Bookbinder’s ticket on inner pastedown reads: Todd and Cote Bookbinders, No. 11, St. Genevieve Street St. John Suburbs.

Contains the engraved armorial bookplate of Shanly with motto “Pro Patria Et Religione” and Thorndale in ms. Shanly Bookplate is not in Franks.

Library call number and “Treasure Room” stamp present.

Stowe, Harriet Beecher. Uncle Tom’s Cabin or Life Among the Lowly. Toronto, Thomas Maclear at 45 Yonge Street, 1852.

Second Canadian Edition.

Printed in double columns by Brewer McPhail and Co. at 46 King Street East.

Two wood engravings at front (one of Auction; second of Arrival in Canada).

Final leaf has list of Books for sale by Maclear.

Additional copies at Library and Archives Canada, University of Windsor, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, Toronto Public Library, etc.

Western Copy 1 is in original paper boards and dated 1853

Includes “Eighth Thousand in Canada” and price of 3 [shillings?]2[pence?].

Back board has advertisement from MacLear for a new History of 1812, 13 and 14.

Smudged stamp reading “Released by U of M Library” on inner board.

Western copy was microfilmed (but the important binding was not) and made available on Canadiana.org. http://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.94114/6?r=0&s=1

Western Copy 2 is rebound in marbled boards with book label reading Elsie M Thompson 44 Herkimer St. Hamilton Ont. Can.

“H.R. Thompson” in pencil on inner pastedown.

John Davis Barnett bookplate on inner pastedown.

First endpaper has Barnett signature, date of “1917” and accession number “#41957”

Some mild foxing throughout.

The Anglo-American Magazine. Toronto: Thomas Maclear, 1852-1854.

Seven extensively illustrated volumes issued in numbers.

Bindings in different styles. First four volumes bound in half calf over marbled boards with late nineteenth century armorial bookplate of Matthew Teefy. Motto “In hoc signo spes mea.” For more on Teefy, see http://history.rhpl.richmondhill.on.ca/390/Exhibit/5

Volumes 5 to 7 in different bindings (Volume 5 in original brown tooled boards with title in gold) and final three volumes with Barnett provenance.