The Differing Meaning of Objects

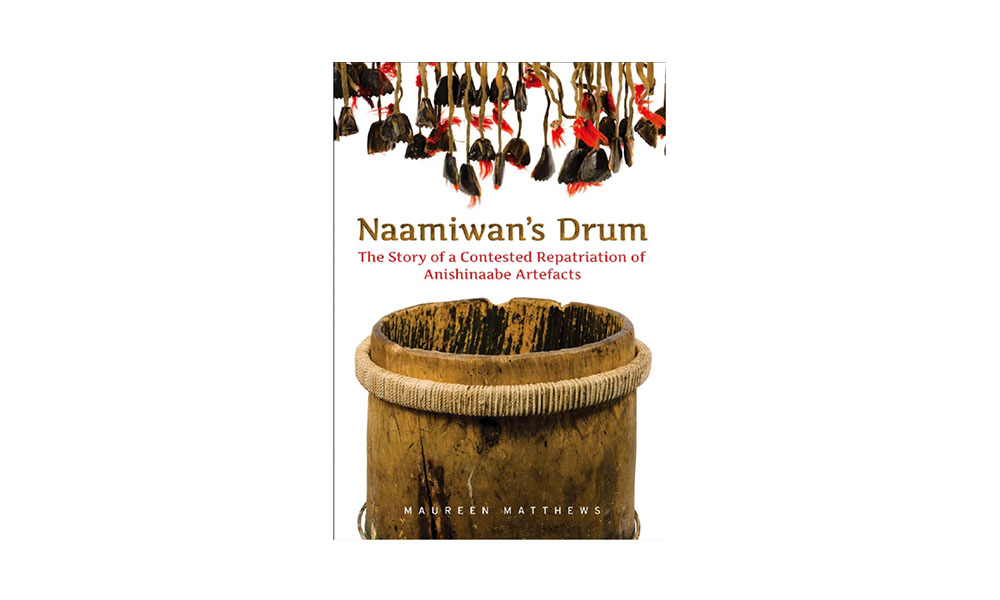

The Huron Missionary Museum operated from 1911 to 1941 at Huron College, with parts of the former museum collection now sitting in storage closets at Huron University. Repatriation is no simple process and the collection descriptions left behind from the Museum’s past give little relevant information about the objects to go forth with repatriation. Maureen Matthews’ book, Naamiwan’s Drum: The Story of a Contested Repatriation of Anishinaabe Artefacts is a seminal work in the study of repatriation. Matthews is a Curator of Cultural Anthropology at The Manitoba Museum who brings forth the story of Naamiwan’s Drum to enlighten readers about the complex nature of repatriation. Naamiwan’s Drum is an Ojibwe water drum belonging to Naamiwan, a leader of the Pauingassi Ojibwe community before his death in 1943. [1] This drum was one of his most significant possessions. Around 1970, a collector claimed that he saved many Pauingassi objects from decay and brought them to the University of Winnipeg. [2] The University of Winnipeg Museum took ownership of these objects and treated them as proper museum artifacts. Taken out of its original context, the cultural meaning of the drum began to shift. Matthews argues that the cultural meaning of collections may not be as transparent as many believe and that museums must conduct thorough research to ensure they understand the cultural meanings of their objects. To many non-Ojibwe people, for example, Naamiwan’s Drum may simply appear as a historic percussion instrument. This makes the drum important, but no more so than any other historic instrument. To Ojibwe people, however, water drums, like Naamiwan’s Drum, are some of the most important historical objects. According to Matthews, they interpret the drum as an animate being, capable of having thoughts and feelings as well as influencing the community. Matthews explains how, when conducted poorly, repatriation can greatly harm source communities. This can happen when museums misunderstand the meaning of objects to the communities from which they came. Matthews brings forth Naamiwan’s Drum as an example of a museum neglecting to understand the meaning behind its objects and conducting harmful repatriation.

From a general perspective, Ojibwe do not believe that all objects are alive, rather, they believe certain objects can encapsulate the influence of important things in the world around them. While the Ojibwe people view most stones as inanimate, some stones, like a uniquely smooth one, can represent the presence of a living thing. [3] Ojibwe people thus hold more personal connection with animate objects like Naamiwan’s Drum because they see it as an animate being. Naamiwan’s Water Drum is thereby extremely meaningful to the Ojibwe people because it is an object with significant animate connections to Naamiwan, a member of the Ojibwe community.

Matthews’s book demonstrates how the meaning of objects can vary greatly between two different Ojibwe groups. Naamiwan’s Drum holds significance with the Pauingassi – to which Naamiwan belonged – because Water drums like Naamiwan’s are highly personal items to their owners and families. They accompany their owner to significant life events like healing rituals and cultural events while also providing spiritual guidance. [4] This creates a highly personal connection to the community and family to whom such objects belong. The University of Winnipeg put forth some commendable, although imperfect, efforts such as holding the animate objects in restricted storage so they would stay off display and not face unnecessary disturbance. However, when Naamiwan’s descendent Omishoosh visited the collection, his interactions with the objects did not meet the expectations of university staff who expected him to act in a more traditional Ojibwe way. They thus made incorrect assumptions that the Pauingassi people no longer practiced the culture of their ancestors. [5] When The Three Fires Midewiwin Ojibwe people approached the University to claim repatriation rights of the Pauingassi objects, the University agreed without contacting the Pauingassi. The University of Winnipeg decided that the Three Fires Midewiwin deserved the objects because they maintained more traditional aspects of their Ojibwe heritage. [6] By assuming the changing traditions of the Pauingassi meant they no longer held significant connection with their ancestors, the University of Winnipeg Museum irreparably harmed the source community of these objects.

The lesson that Matthews takes from these observations is that it is the responsibility of museums and collection holders to understand the meaning of objects with their home communities or risk causing greater harm through their mistreatment. In the case of Naamiwan’s Drum, the University of Winnipeg failed to fully understand the meaning of Pauingassi objects within their collection. They knew that the drum held significant value to the Ojibwe people but did not put forth efforts understand its meaning to the Pauingassi Ojibwe.

Rather than repatriating the objects to Three Fires Midewiwin Ojibwe, Matthews argues that a proper course of action in this process of repatriation would include practical relativism. Matthews describes practical relativism in relation to repatriation as researching and understanding the meaning of the object to communities connected with the item. [7] If the University of Winnipeg conducted practical relativism in their process of repatriating the Pauingassi collection, they would understand the continued meaning of such important objects to the community. This example shows that repatriation requires expert knowledge of the ideas and beliefs of the original owners of the objects in addition to well-maintained connections with source communities. Only then can a museum fully understand the meaning behind significant objects and make informed decisions. Without conducting practical relativism, museums risk misinterpreting or neglecting to consider the many different possibilities of object meaning. This can cause irreparable harm to stakeholder communities like the Ojibwe Pauingassi.

Matthews’ work demonstrates the importance of conducting repatriation in a good way. It is not as simple as repatriating objects to the first community who asks for them. Museums and collection holders must conduct extensive research, modeled by practices such as practical relativism and community connections, to understand the cultural beliefs of all stakeholders and properly identify the best course of action for each object.

Notes

[1] Maureen Matthews, Naamiwan’s Drum: The Story of a Contested Repatriation of Anishinaabe Artefacts (Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 2016), 10.

[2] Matthews, Naamiwan’s Drum, 131.

[3] Matthews, Naamiwan’s Drum, 66.

[4] Matthews, Naamiwan’s Drum, 4.

[5] Matthews, Naamiwan’s Drum, 177-178.

[6] Matthews, Naamiwan’s Drum, 232.

[7] Matthews, Naamiwan’s Drum, 243.