Continued Colonialism and Museum Collections

A photograph of four likely knobkerries found in the Huron Missionary Museum collection. Each classified in the Waller collection inventory as a “Club Used for Infanticide.” Photograph taken by Remi Alie

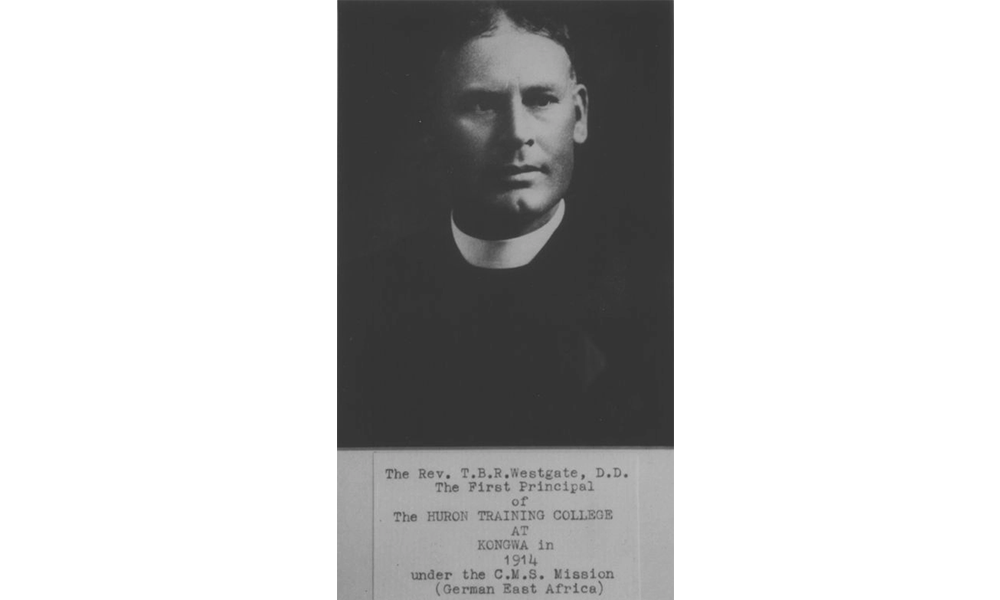

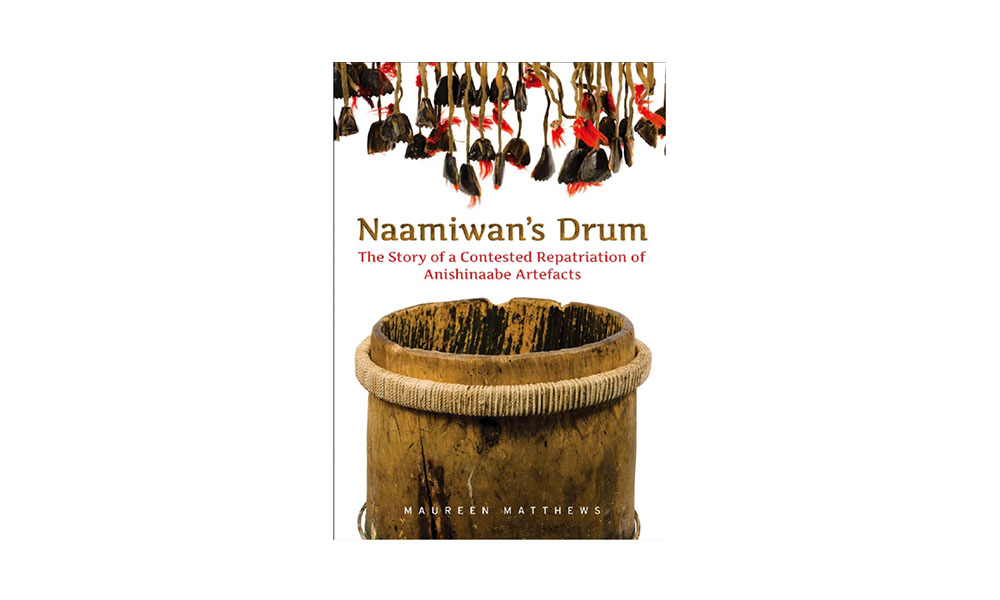

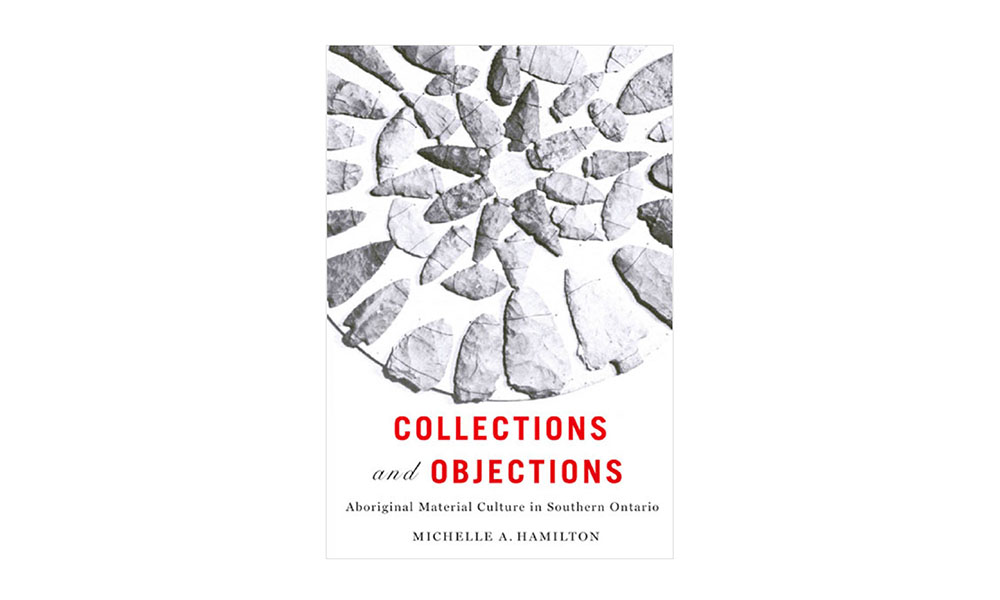

During its operation between 1911 and 1941, the Huron Missionary Museum took a generic and inaccurate approach to describing artifacts within its collection. These descriptions remain as the only pieces of information associated with the artifacts in the Huron Missionary Museum collection. This post and the following will each bring forth one type of object from the Huron Missionary Museum collection that demonstrate the issues with providing inaccurate and generic information about artifacts and the cultures they come from. The inventory of the Huron Missionary Museum describes the artifact type featured in this post as “Club[s] Used for Infanticide.” The true name of these artifacts is knobkerrie. A knobkerrie is a common type of weapon used by many East African cultures for hunting and warfare. These weapons feature long wooden handles that thicken at the top to create a circular shape. The top acts as a club to inflict damage upon targets. [1] The description of the knobkerrie inaccurately depicts the source communities of this artifact. Rather than describing the true use of the knobkerrie as a weapon for hunting and warfare, the museum administrators chose to portray the weapon as a tool used solely for infanticide and thereby inaccurately portray the source community. “Club[s] Used for Infanticide” continues to be the only description tied to these knobkerries in the Huron Missionary Museum. Inaccurate and generalized descriptions of artifacts misrepresent the people they come from. The so-called “Club[s] Used for Infanticide” demonstrate how some museum administrators in the early twentieth century chose to misrepresent the cultures of artifacts in their collection. Colonial museums should expand repatriation efforts to begin healing the harms of misrepresentation. The collection inventory used in this post comes from the Principal of Huron College during the Huron Missionary Museum’s Operation. From 1911-1941, Principal Waller created an inventory of the Huron Missionary Museum Collection. Remi Alie, a student at Huron College, transcribed this inventory as part of a project in the class “HIST 3801: The Historian’s Craft” at Huron University College. Items in the Huron Missionary Museum feature descriptions that inaccurately depict the cultures from which the objects originate. The Huron Missionary Museum collection features several knobkerries or similar objects solely classified in Waller’s collections inventory as a “Club Used for Infanticide.” Rather than a tool created for infanticide like Waller’s inventory insinuates, many East African cultures used knobkerries in large-scale warfare or for hunting. While, like any other weapon, a person wielding a knobkerrie could commit infanticide, this was not the intended purpose of the weapon. [2] Describing the knobkerrie as an infanticide club demonstrates that organizers of the Huron Missionary Museum inaccurately represented cultures instead of presenting a factual and respectful history. A person viewing this description could believe this to be a purpose-built tool for infanticide. This grossly overstates the prevalence of infanticide and casts an overtly violent depiction of the East African communities using weapons like the knobkerrie. The inaccurate descriptions of artifacts in the Huron Missionary Museum continue to be the main source of information available to those looking into the collection. Thus, these descriptions still inform much of the University’s knowledge about this collection. As described in the second post of this series, in Collections and Objections, Michelle Hamilton, a history professor at Western University, argues that early twentieth century collectors of Indigenous objects, like David Boyle, viewed themselves as paternal experts on Indigenous cultures while dismissing the knowledge of Indigenous peoples. [3] This example of the knobkerrie presented as an infanticide club shows that such collectors abused this reputation of expertise at the expense of Indigenous peoples in the various countries that they collected artifacts from. They presented inaccurate information that remains attached to objects in collections like the Huron Missionary Museum. For example, the recent inventory of the Huron Missionary Museum collection relies on the binders created by Principal Waller. Without significant research applied to this collection to find more accurate information, the inaccuracies of Principal Waller will continue to inform those looking into the Huron Missionary Museum. These examples demonstrate the importance of expanding efforts to understand the meaning of objects in colonial collections. The depiction of the knobkerries as solely “Club[s] Used for Infanticide,” shows that museum organizers created inaccurate depictions of objects despite presenting themselves as experts on the subject. That such descriptions remain attached to objects in the Huron Missionary Museum brings further urgency to expanding research efforts to better understand items in the collection for eventual repatriation. Future researchers trusting the inventory descriptions of the Huron Missionary Museum may mislead readers and continue the colonial perspectives put forth by the original Huron Missionary Museum administrators. Furthermore, the current state of the Huron Missionary Museum descriptions makes repatriation extremely difficult. With little knowledge of the collection, Huron University risks incorrectly repatriating objects in the collection. The example put forth by Maureen Matthews with the artifact, Naamiwan’s Drum, at the University of Winnipeg as described in post 3 of this series, serves as a warning for the consequences of improper repatriation. [4] Universities and museums wanting to increase decolonization efforts should conduct proper repatriation through the use of practical relativism, otherwise known as conducting proper research of the object’s history and communities it may belong to.Notes

[1] Cyril B. Courville, “War Weapons as an Index of Contemporary Knowledge of the Nature and Significance of Craniocerebral Trauma: Some Notes on Striking Weapons Designed Primarily to Produce Injury to the Head,” Medical Arts and Sciences: A Scientific Journal of the College of Medical Evangelists 2, no. 3 (July 1948): pp. 85-111, 89. [2] Courville, “War Weapons,” 89. [3] Michelle A. Hamilton, Collections and Objections: Aboriginal Material Culture in Southern Ontario (Montreal, QC: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2010), 169. [4] Matthews, Naamiwan’s Drum, 177-178.