The Author

Among the voluminous mass of Coleridge’s various writings, ranging from polemical essays to theological and philosophical meditations, his poems comprise, only a small body work. In qualitative terms, however, they are among the great achievements of first-generation Romantic poetry (O’Neill & Mahoney, 173). It is clear that there is a relationship between Coleridge’s religious and philosophical thinking, and his poetic imaginings – to read and think about any of his poems is to enter an interpretative labyrinth.

Coleridge was born at Ottery St Mary in Devon, the last child in a family of ten. His father died in 1781 when he was only eight. Soon after, he was admitted to the school Christ’s Hospital in London. More intimate details of his childhood are given in a series of remarkable autobiographical letters to his friend Thomas Poole. In one of these he speaks of his very early reading of such works as the Arabian Nights entertainments, and say that “before I was eight years old, I was a character.” A ‘character’, in the sense of a deeply and richly idiosyncratic person, he was to remain throughout his life (Selected Letters, 59).

Throughout the 1790s, Coleridge’s radical sympathies are evident in his various prose, writings, and lectures, including Rime of the Ancient Mariner. Much controversy has raged over the question of whether Coleridge, in later life, renounced his youthful siding with cause of reform, but two consistent strains throughout his career are his longing to unite hear and head, and his conviction of the need for a religious solution to the contradictions of existence (O’Neill & Mahoney, 173). Coleridge saw his endeavours as:

“Directed to persons and characters supernatural, or at least romantic; yet so as to transfer from our inward nature a human interest and a semblance of truth sufficient to procure for these shadows of imagination that willing suspension of disbelief for the moment, which constitutes poetic faith.” (Biographia Literaria, vol. 2, p.6)

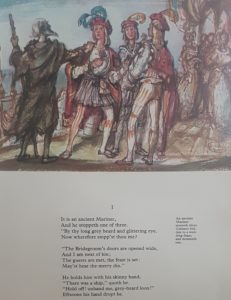

The description fits the Rime of the Ancient Mariner, which remains, through its various incarnations, a poem that displays Coleridge’s metrical ingenuity; capacity to create haunting image; knowledge of guilt, alone-ness, and existential terror; and strong desire for community. The Mariner’s slaying of the albatross permits Coleridge to explore all that opposed his optimistic hopes.

Coleridge’s career was dogged by personal difficulties, his marriage effectively broke down after he fell in love with Sara Hutchinson, Wordworth’s sister-in-law, a relationship that was dogged by unhappiness and distress. His opium habit caused him endless problems, and he began to doubt his ability to write poetry. His close, but difficult, relationship with Wordsworth underwent a major crisis in 1810 when adverse remarks supposedly made about him were passed through a mutual friend. Despite Wordsworth’s dignified refutations and a patched-up reconciliation, the relationship between the two authors of Lyrical Ballads would never recover its former closeness (O’Neill & Mahoney, 174).

Coleridge emerges in his poetry and criticism as a champion of the imagination, conceived of as the creative power to bestow life and meaning on a universe that would otherwise be dead and spiritless. He is aware, however, that what may look like creative triumph may, from an entirely different perspective, seem to be projective delusion – a “concern of ‘Constancy to an Ideal Object'” which is ironic since Coleridge longed to harmonize but whom we value for his readiness to articulate obstalces in the way of harmony and synthesis (Ibid, 174).

The Poem

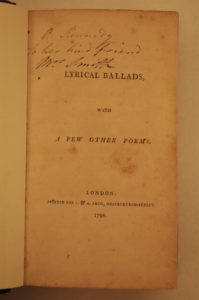

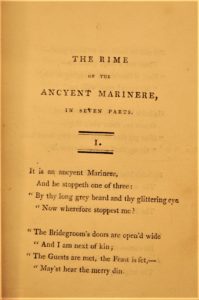

The poem, Rime of the Ancient Mariner, was initially published in Lyrical Ballads (1798) where it opened the volume and, in keeping with a work “professedly written in imitation of style as well as the spirits of the elder poets” (Advertisement to Lyrical Ballads, 1798), was entitled, “The Rime of the Ancyent Marinere”.

Much later in Biographia Literaria (1817), Coleridge himself in describing the rationale of his contributions to Lyrical Ballads, spoke of seeking to “procure for these shadows of imagination that willing suspension of disbelief for the moment, which constitutes poetic faith […] With this view I wrote the “Ancient Mariner””. The poem generates such a “suspension of disbelief”, and yet Coleridge decided to add a gloss in the 1817 text, where the poem appears removed of many of its calculated archaisms, which had been heavily criticized when it was first published (Biographia Literaria, Chapter XIV).

Compellingly the poem blends power and indeterminancy. If the 1817 text obliges us to respond to the voice of the gloss, the gloss, as suggested already, has a sureness at odds with the openness to possibility exhibited by the epigraph by Burnet: “[…] more invisible than visible Natures in the universe of things […] The human intellect has always sought the knowledge of these things, but never attained it.” (O’Neill & Mahoney, 189). The gloss exhibits a will to rationalize and moralize the events which transpire in the poem, which in the poem affect us as hard to explain, even arbitrary.

Interpretative rather than evaluative controversy has always attended the poem. Some read the poem as portraying a clear moral vision: the mariner’s killing of the albatross violates the sanctity of bonds linking humanity to the natural world; his is punished; repents when he blesses the water-snakes; returns to land, and offers a moral. If the gloss is accorded authority in reading the poem, it reinforces this moral reading since at several moment it articulates a religious understanding of the poem’s events (Ibid, 188).

Throughout, the poem infuses clarity and enigma. Stanza after stanza charts the mariner’s experience through unforgettable, sharply etched images. Physical description is given an unnatural beauty and clarity that makes it seem revelatory. However, the connection between events is often harder to grasp than the sheer momentum of the narrative. So, why does the mariner kill the albatross? Coleridge is all silence on the subject, the reader not witnessing the actual murder event, rather the emphasis is placed on the suffering of the murderer (Ibid, 190). What is certain is that we see the mariner as someone by whose experiences we are imaginatively compelled whose final meanings of these experiences are displaced by variants of interpretations.

Coleridge, Samuel T. Selected Letters, ed. H.J. Jackson. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Coleridge, Samuel T. Biographica Literaria. 1817.

Romantic Poetry: An Annotated Anthology, ed. Michael O’Neill and Charles Mahoney. Malden & Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2008.